Australia: 13 11 14

US: 988 Lifeline

UK: The Samaritans – 116 123

In everyone’s life there are a series of inflection points – those lines in the sand that split things into before and after. That applies to you, and to me, and to the most famous and prolific professional cyclists in the world. The more famous you get, the better-known these events become, forming part of a public narrative of your life and career – but then time comes along and parts of those story fall by the wayside.

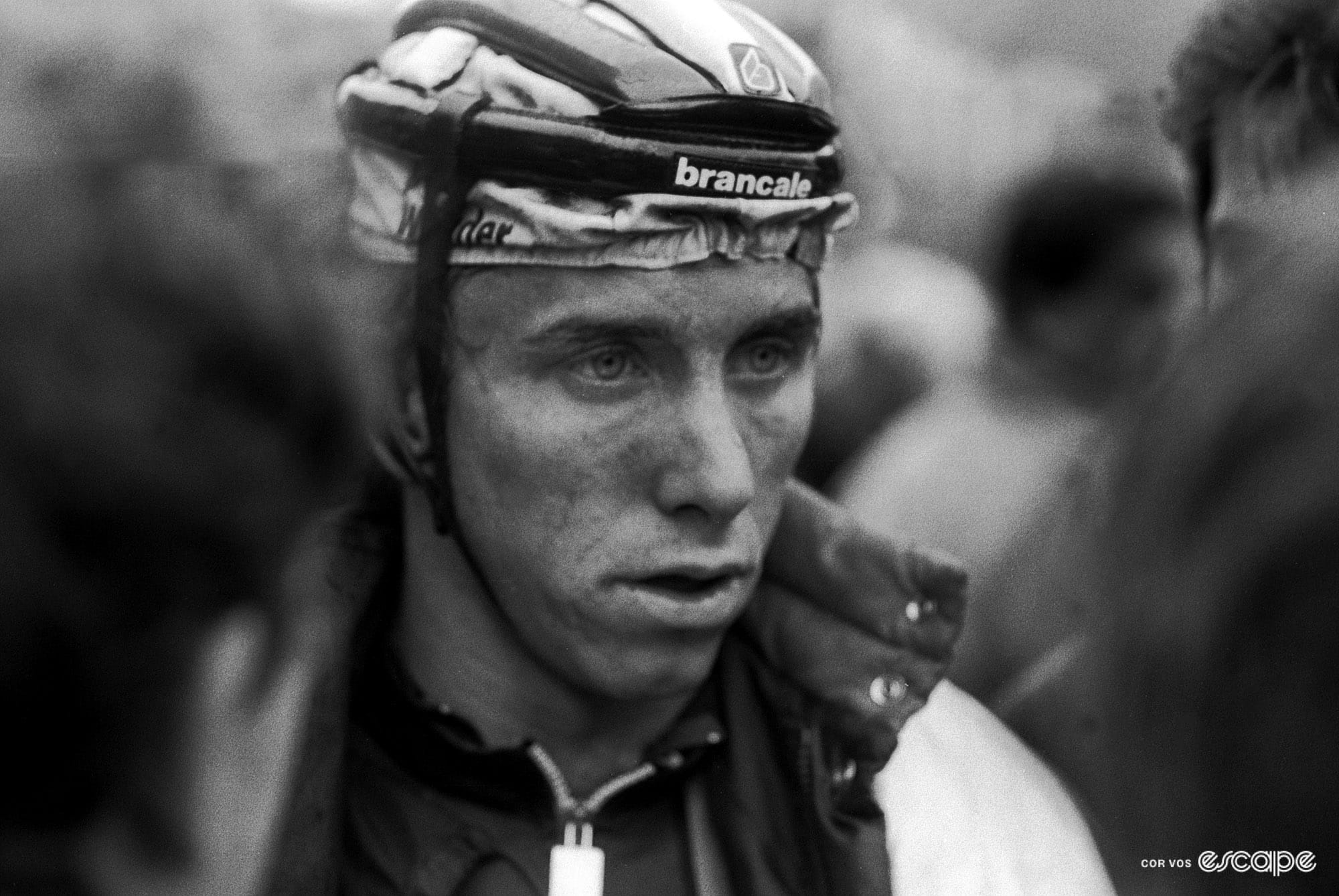

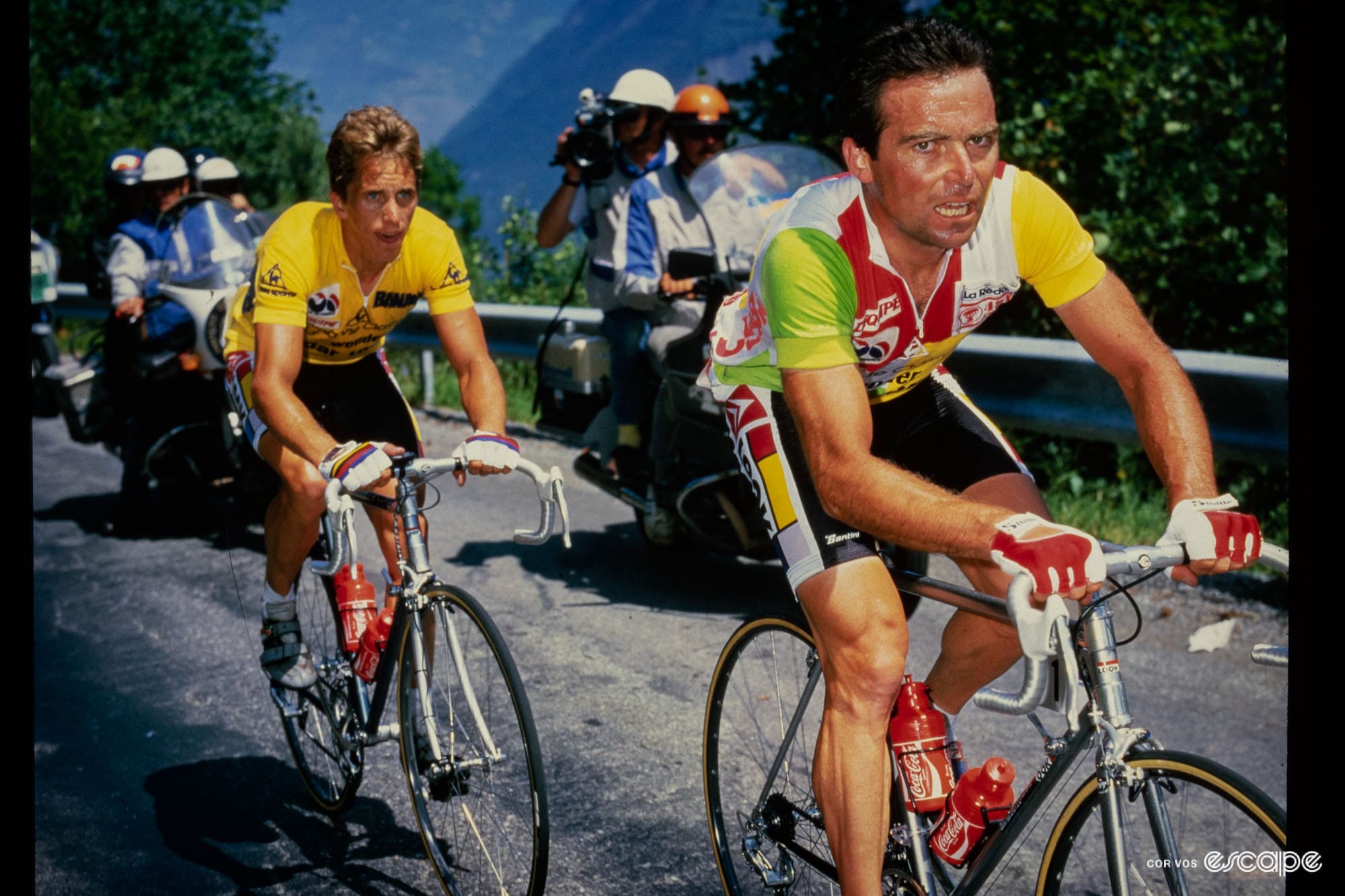

So, when you think of Greg LeMond – the three-time Tour de France winner (the only American still with a Tour title) and two-time world champion – you probably think of the 1989 Tour de France, when Lemond won the tightest-ever edition of the (men's) race in the final-stage time trial, knocking Laurent Fignon out of the yellow jersey by eight measly seconds after three weeks of back and forth racing.

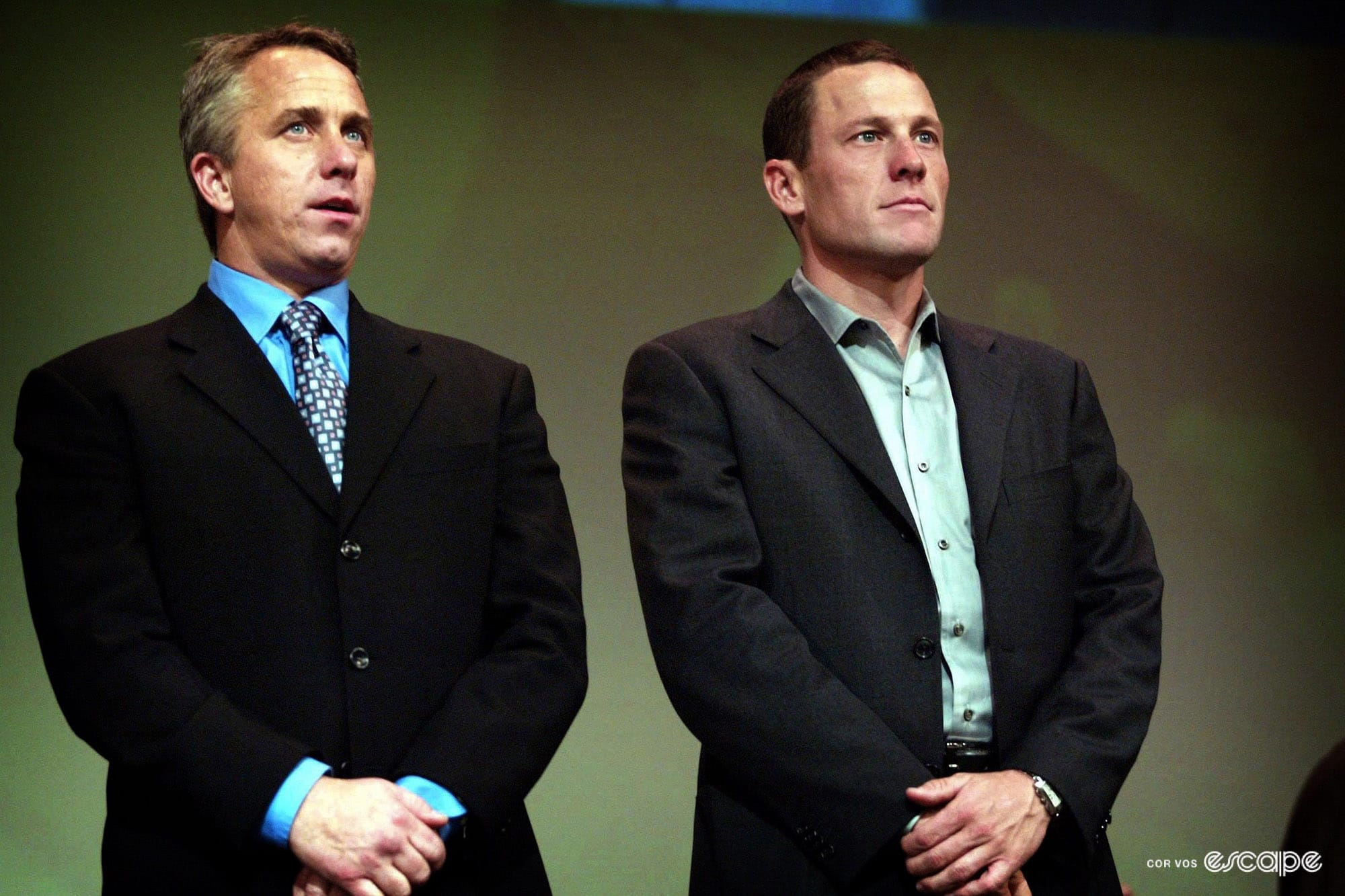

Maybe, when thinking of Greg LeMond, images are conjured of his innovative aero bars and helmet, his aggressive and daring riding. Maybe you’re thinking of his time post-retirement, where he found himself at the centre of spats with the likes of Lance Armstrong and Floyd Landis, his personal integrity clashing forcibly with a sport that was trying to bury its head in the sand and pretend everything was OK.

And now? Well, now he’s in his 60s, has a full life, a bike company, and a place in the sport that is respected and revered. Greg LeMond is the 1989 and 1986 and 1990 Tour de France wins, and his public fallings out with those that tried to bully and silence him. But there’s one element of his life that’s fallen into this weird in-between place where it’s forgotten by many, if they ever knew about it to begin with.

Less than a year after winning his first Tour de France – in the prime of his career, aged just 25 – Greg LeMond was shot and almost died.

As part of a new podcast series we’re launching at Escape Collective – we’re calling it the ‘Rabbit Holes’ podcast – Jonny Long and I will be digging into an intriguing question or story from the world of cycling each month. For the first instalment, this seemed a pretty good place to start: a Grand Tour champion, violence, intrigue, rehabilitation, and redemption. But it’s also, as you’re about to learn, a deeply human story of forgiveness, resilience, and love.

But if we’re to boil all of that down to a single question – and we have to start somewhere – we want to know this: who shot Greg LeMond?

Trailer above, full episode at the bottom of this page.

To unpick this question, I jumped on a call with Greg LeMond and his wife Kathy to delve almost 40 years into the past. They were at home in the States – they live in Knoxville, Tennessee – and Greg was sitting in front of his iPad in a bright, airy room, waiting to be peppered with questions from an Australian he’d never met before and an Englishman who he had (Escape contributor Chris Marshall-Bell helped set up the call and contributed questions).

It ended up being a big and sometimes raw chat – one that spanned the past and the present, and touched on the ways that the shooting incident came to define LeMond’s career, and life. Along the way we learned about the fear and uncertainty that defined that period, and the ripples from it.

But on the morning of April 21, 1987, that story was still unwritten.

On that day, Greg LeMond was at home in the US, nursing a broken wrist that he’d picked up at Tirreno-Adriatico, with his defense of the Tour de France hanging in the balance. LeMond had begun training again, and was vaguely hopeful of being able to regain form in time for the Tour, but there was work to be done.

“What I was told by all the doctors, all the specialists, is that with the navicular,” LeMond said. "And I'm like, ‘come on’. I went home for maybe two weeks and stopped riding, but after two weeks, I'm going ‘OK, the swelling is down, it doesn't hurt,’ So I started riding my bike right away. I wasn't going to stop. My hope was to get back [by] the Tour that year or sooner.”

LeMond and his family – his wife Kathy and his first son Geoff – had flown from their base in Belgium back to California for the recovery period, giving LeMond a chance to reconnect with his family back at home and navigate the stress of contract negotiations. At the time, he was in his final year with Toshiba-La Vie Claire, and things felt precarious. The sport was changing – doping was becoming more prominent, and Lemond’s relationship with La Vie Claire was tenuous since he’d beaten his team co-leader, Bernard Hinault, to the win at the previous Tour de France. In the process, internal divisions in the team had made for a challenging environment and Lemond was left wondering where he’d end up next.

That’s the context of where Greg LeMond’s career was at in 1987 – one of the most exciting talents in the sport, with some huge results already, but with injury woes and career uncertainty. Perhaps that was a factor in him seeking an activity to take his mind off things: a fateful decision that would go on to have big consequences for the course not just of his career, but the rest of his life.

It began with a discussion at a family dinner on Easter Sunday.

“The next day was the opening of Turkey season, and I grew up trap shooting; I grew up quail hunting,” LeMond explained. "I wasn’t a big hunter, but I was a pretty good shot. My uncle owned a farm about 60 miles from where I was living in Sacramento, California, and [he] said, ‘Well, why don't we just go, spend the night there and bag some turkeys.'

"We got there about 6.30, 7 in the morning. We were in camouflage, and we really weren't experienced at all in doing this. I'd never hunted turkey before, but turkeys roost and they feed. And the idea was my uncle knew where they were roosting and feeding, and we were just going to lay in these wild blackberry bushes to see what we could get. It was really more of a get-together. It wasn't really meant to be a big hunt.”

That calm-before-the-storm quality is how Kathy, remembers it too – as a chance for Greg to reconnect with family members and take some time away from the pressures of his career, before getting back to the bike.

“We were scheduled to go back on Tuesday to Europe. And his uncles were like, ‘come on up to the ranch, and you can do some bird hunting and then ride your bike back home,’” Kathy told us, before pausing a little as she remembered something else. “It was weird because he came back to the house twice, to kiss me goodbye. And he's like, ‘I really don't want to go’. And I'm like, ‘Well, you never see your uncles – just do it.’ And I never really gave it another thought.”

That Easter Monday, in the early morning light, Greg and his hunting buddies rose early. Joining the Tour de France champ was his uncle, Rodney Barber, and his brother in law, Patrick Blades – his sister’s husband.

“My brother in law split off to the right, my uncle went to the left, and I went kind of down this draw where it was supposed to open up,” LeMond recalled. "And when I got to that point, I backed myself into the berry bush and camouflaged, just kind of in front of the bush. I sat myself down, looked around and couldn't see anybody, and stood up to see where my brother in law was and my uncle. But as I turned and stood up to look to my right, I heard a shot go off.”

There are moments in life where time loses its normal structure: moments where minutes feel like hours, or the opposite. And there are moments when adrenaline or shock send your body into a kind of advanced consciousness where you take in all the information around you, a second or two that you can retrace in minute detail even years later.

“I actually thought my own gun went off," LeMond said. "Then I looked at my gun – no, that didn't go off. Then I think I called out, ‘did you shoot?’ And then I looked down, and saw blood coming out of my ring finger, and I realized [I’d been shot]. But as I tried to speak – let's just say it was simultaneous – I tried to speak, and I couldn't speak. I was, like, gurgling blood – I couldn't speak. I had a collapsed lung at that point, and apparently I was bleeding internally. ‘Wow, I'm shot.’”

You can probably imagine the panic setting in for LeMond here, but imagine for a moment that you’re his uncle and his brother in law. For Rodney – LeMond’s uncle – there was utter confusion. But for Greg’s brother-in-law Patrick, there was something worse to contend with: the realisation that he’d just shot someone.

“You go through this little shock period where you're kind of, like trying to understand what's happening,” LeMond said. "And my brother in law came up, and he just saw that he shot me. And [then] my uncle showed up. I had a stream of blood coming out of the back of my lower neck, just like a constant stream. My uncle tried to downplay it, but I think my brother in law, Pat, thought he'd killed me."

That awful realisation almost turned the situation even more tragic, because Patrick was sent absolutely spiralling by the realisation. He’d just accidentally shot his wife’s brother – a Tour de France champion and household name – and was convinced that it was fatal, and his thoughts turned to the darkest possible solution.

“He freaked out,” LeMond told us. "He did try to, you know … he made an attempt to shoot himself at the time, and I was conscious enough to tell my uncle to grab the gun, empty it, and make sure he's safe – because I was living. So we sat there for five minutes or so, getting that calmed down."

With the gun disarmed and Pat out of immediate danger, LeMond’s uncle took off for the house to call for an ambulance – this was an age before mobile phones. A near-dying LeMond needed to help orchestrate his way out of the situation, and figure out the logistics of getting himself to a hospital as quickly as possible.

"My uncle ran to the house, which was a three-, four-minute walk – not far,” LeMond explained. "And he called an ambulance, and we went back, waited there for five or 10 minutes. It seemed like it took forever. I don't know how long it really was, but I realized nobody was coming. Or, at least I didn't think anybody was coming.

“We had told them the address, but it's a large area … So I said ‘we gotta go to the gate’. My brother in law and uncle lifted me up, and they carried me to a truck and drove me to the top of the property. The property sat on a pretty good vertical hill – 400-500 feet high – and the gate was closed, and everybody was waiting at the gate. So it was very fortunate that we took that action to get there.

"By the time I got to the ambulance, I was really starting to fade, and they kept trying to keep me awake by asking my address. I don't know how many times. I still know that address now because I repeated it about 60 times.”

LeMond was fading fast, but luckily there was a police helicopter flying nearby and the first responders called ahead to organise a pickup. It’d be touch and go, with LeMond drifting in and out as his body began to shut down.

“You know, the funny thing is it didn't hurt, really. It was kind of like going to sleep – you have a really hard time staying awake. It’s very vague the timing of it – I’d say maybe 10 minutes inside the ambulance, and I think 10 minutes in the helicopter – and I'd lost 70% of my blood volume by the time I got to the hospital. So had I been taken to the hospital by ambulance, I would have died on the way, no doubt. So I was very lucky,” LeMond said, the words rushing out of him, the tension of the moment still palpable after all these years.

So what does it feel like to be almost dying, Greg? “I’ve seen movies that really kind of replicate what I felt," he said. "There’s one – I forget the name – with Robert Duvall and he’s dying, he’s gurgling up blood … the way he looked, that’s how I felt. The first thing I did, really, was I started thinking about my family – ‘I can't die’. I started thinking about my wife, my kids. I don't want to die.

“That was really what was foremost in my mind; I don't want to die. I want to see my wife. I want to see my son, Geoff. And, I gotta be there when my second child is born. I think that's what happens when you’re near death – your mind goes to all your memories and what you're living for.”

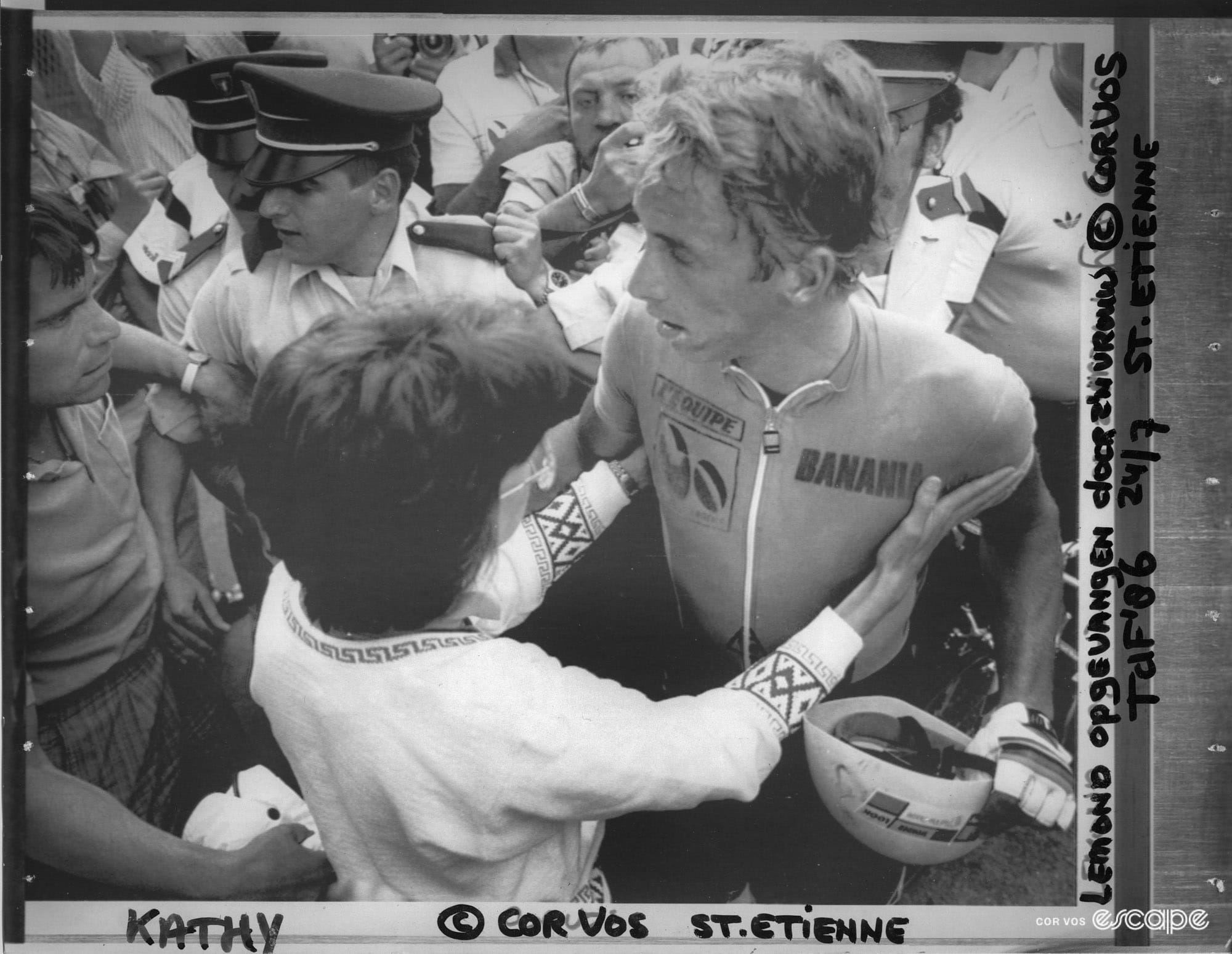

Meanwhile, back at the family home, Kathy LeMond – almost eight months pregnant – was making breakfast completely unaware of what was going on. On the menu: pancakes.

“I was in the kitchen early making pancakes for Geoff, who was two, and the phone rang,” Kathy explained. "It was somebody who said they were calling from UC Davis Medical Center and that my husband had been shot. I had actually forgotten that he was hunting in the morning. She kept saying she was at UC Davis Medical Center, and that they had just brought him in in a helicopter. And I said ‘is this one of those things where he's actually dead and you're not telling me, you're just gonna get me there and then tell me?’ And she said, ‘No, he was alive when they took him off the helicopter.’”

UC Davis Medical Center was about 40 minutes drive from where Kathy was, so she started gathering up Geoff and rushed to get there as quickly as possible. “I called Greg's sister – she had two little toddlers – and I said that Greg had been shot, and I was just going to put on clothes and drive to the hospital," she said. "I went and picked her up, and she got in the car with her little kids, and I had Geoff and drove to UC Davis.

“When we got there, it was so bizarre. I went into the emergency room, and no one really said anything to us. They just put us in this [waiting] area, and then the press started showing up – I guess it must have been on the police radio, and people started hearing that Greg had been shot … We were sitting in this public place, and everyone was asking us everything, but I knew nothing.

“Greg was still in surgery, but whenever I called up to the OR [for an update] they just said, you know, ‘we can't talk, we're trying to save his life here. We'll let you know when we know.’ So we really sat in limbo for a long time, not knowing if he was going to make it or not make it. And for me – I mean, I'm not a religious person – but I was trying to make a deal … ‘please, please, please, let him survive this’. I don’t need anything more. All I want is for him to survive this.”

Kathy was, understandably, distressed – that’s apparent even all these years later – but things were about to get even worse. Not only was she facing the prospect of her husband suddenly losing his life, but she was with Greg’s sister – also called Kathy – when the news came through that her husband had pulled the trigger and was suicidal as a result. And that was just the beginning.

“We found out that it was [Greg’s sister] Kathy's husband who actually shot Greg, and that made it even worse,” Kathy LeMond explained. "He was in a hospital across town because after he shot Greg, he tried to kill himself because he thought he killed him. So the two of us are sitting there, just waiting to hear. I called my mom to talk to her, and I was on the phone with her, and I guess I was making strange noises, and I hadn't realized that I had gone into labor. And so she said, ‘you need to call your ob-gyn – I think you're in labor.’”

With Kathy in labour, her brother-in-law on suicide watch, and her husband in surgery, there was one medical emergency on top of another on top of another and very little time for the couple to reconnect. Kathy was about to get whooshed across town to deal with the impending birth of their child, and Greg was hardly out of the woods yet, either. She remembers the moment in vivid detail: the panic, the fear, the visual horror.

“Greg came out of surgery, and they put him into this recovery room with all these people… he was hanging in this kind of a sling over the hospital bed, and all the nurses and everyone were around him,” Kathy said. "He wasn't conscious yet, and he was just dripping blood out of all the holes. He had, I don't know, 40 or 50 holes in his body.

“It was so awful … blood is so red and sheets are so bright white. And there was just all this blood dripping out of him still. My doctor just said ‘tell him what you need to tell him’, and then I had to go to the high-risk hospital for pregnancy across town. And that's where I stayed for the next 48 hours.

"My sister, who was an ER doc at the time, flew out from Milwaukee, and she stayed in the room with Greg, and Greg's mom stayed with me at my hospital – and we prevented Scott from being born for almost another month; I was on medication for that entire month, in a non-progressing labor for a month,” Kathy reminisced. “So, yeah, it was really something,” she added, with more than a little understatement.

So what do you say to your husband when you’ve just gone into labour and he’s just been shot? How do you articulate the enormity of what’s going on? And how can you squeeze a universe of fears and anxiety into a few snatched moments in the chaos of a hospital recovery room? According to Kathy, you’re not thinking of career implications or personal ambitions: everything gets pared back to the bare essentials.

“I don't know what I said to him, but I'm positive I told him how much I loved him," she said. "There's no doubt about that. But other than that, I don't know. I'm just positive I told him that, and please be strong. Don't leave. Please don't leave.”

To hear the rest of the story of Greg LeMond's recovery – the contract negotiations, the ongoing toll it continues to take on the LeMonds, and the forgiveness and acceptance they have reached – become an Escape Collective member. If you're signed in, you'll see the full episode in a player below.

Subscribe to Rabbit Holes on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Did we do a good job with this story?