The 2024 season was a big one for Sarah Gigante (AG Insurance-Soudal). For years her vast potential had been thwarted by illness and injury, but in 2024 the Australian climber finally started to show the cycling world what she was truly capable of.

A win at the Tour Down Under was an emphatic start. Then came fifth on a stage of the Vuelta Femenina and seventh overall at the biggest race of the year: the Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift, including eighth on the race-defining Alpe d’Huez stage. Throw in some promising breakaways throughout the year – not least a 120+ km move at Liège-Bastogne-Liège – and the young Aussie’s star was definitely on the rise.

But Gigante was also struggling.

She’d long had a dull ache in her right leg at rest, but in mid-2024 that ache turned into numbness and considerable pain during hard efforts on the bike – including during her impressive Tour de France Femmes. By September the pain had become unmanageable and “pushing through was no longer an option. Even recovery rides became very painful, and the aching at rest off the bike increased as well.”

By November, Gigante had been diagnosed with external iliac artery endofibrosis (EIAE). A week later she was in surgery to treat the condition, forcing her off the bike for months.

Gigante’s story is an increasingly common one in professional cycling these days. It seems like every few months we hear about another pro rider forced from the bike due to an iliac artery issue. Fabio Jakobsen is the most recently affected, but in the past decade or so, many of the sport’s big names have been sidelined as a result of this debilitating condition – Marianne Vos, Pauline Ferrand-Prévot, Bob Jungels, Fabio Aru, Zdeněk Štybar, and Amanda Spratt to name just a few.

From the outside it seems like the condition is becoming more prevalent. But is it really? And what do we currently know about EIAE, why it happens in cyclists, and why it’s so rare in the regular population?

Let’s start with the basics.

What is external iliac artery endofibrosis?

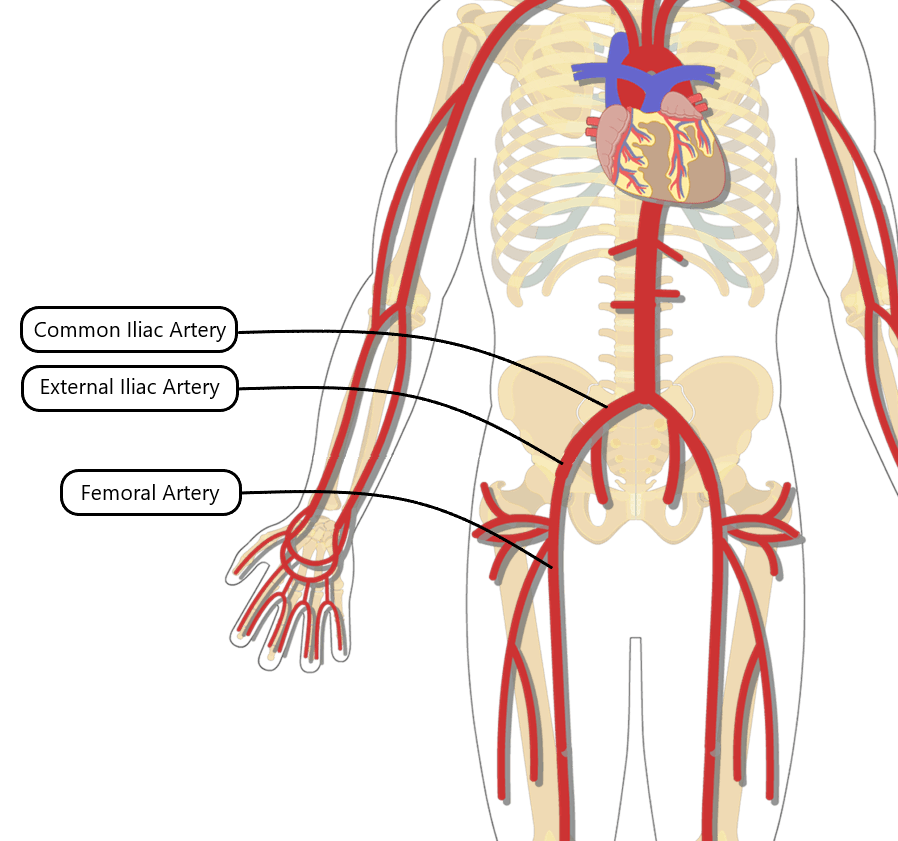

The iliac arteries are the large blood vessels in the abdomen responsible for moving blood from the heart down into the legs. In the abdomen, the aorta – the largest artery in the human body – splits into the common iliac artery on each side, which then splits into:

- the internal iliac artery, to bring blood to the pelvic and gluteal muscles

- the external iliac artery which descends into each leg to supply the quadriceps and other working muscles.

It’s the external iliac artery that’s most prone to damage in professional cyclists.

If the external iliac artery is narrowed or compressed, blood flow is limited and the muscles of the legs don’t receive the volume of oxygen they need during intense efforts. This can lead to a range of symptoms: cramp-like pain, numbness, swelling, a heavy feeling, or an inability to produce power. Any or all of the quads, calves, glutes, hamstrings, or feet can be affected. These sensations normally subside a few minutes after the intense effort ends.

Here’s how Sarah Gigante described the pain she experienced prior to her EIAE diagnosis: “My whole leg, especially my quad, felt like it was being set on fire, even when riding quite slowly.”

We sometimes hear of this condition referred to as flow limitations in the iliac artery (FLIA) – as in Picnic PostNL’s announcement of Fabio Jakobsen’s lay-off. This is an umbrella term that highlights that the condition can occur in other vessels besides just the external iliac artery (such as the common iliac artery or the deep femoral artery) and the fact that the narrowing can be due to arterial kinking rather than – or in addition to – endofibrosis.

But most commonly, the condition occurs in the external iliac artery (more than 90% of the time), and we normally hear it referred to as external iliac artery endofibrosis.

So what is this condition exactly?

Did we do a good job with this story?