Each October for the past three years I’ve watched the Team Lidl-Trek off-season camp with great enthusiasm. No, I’m not that much of a fanboy that I stalk off-season camps that closely, but this one is different. That’s because it is an unlikely combination of my two sporting passions: cycling and hockey.

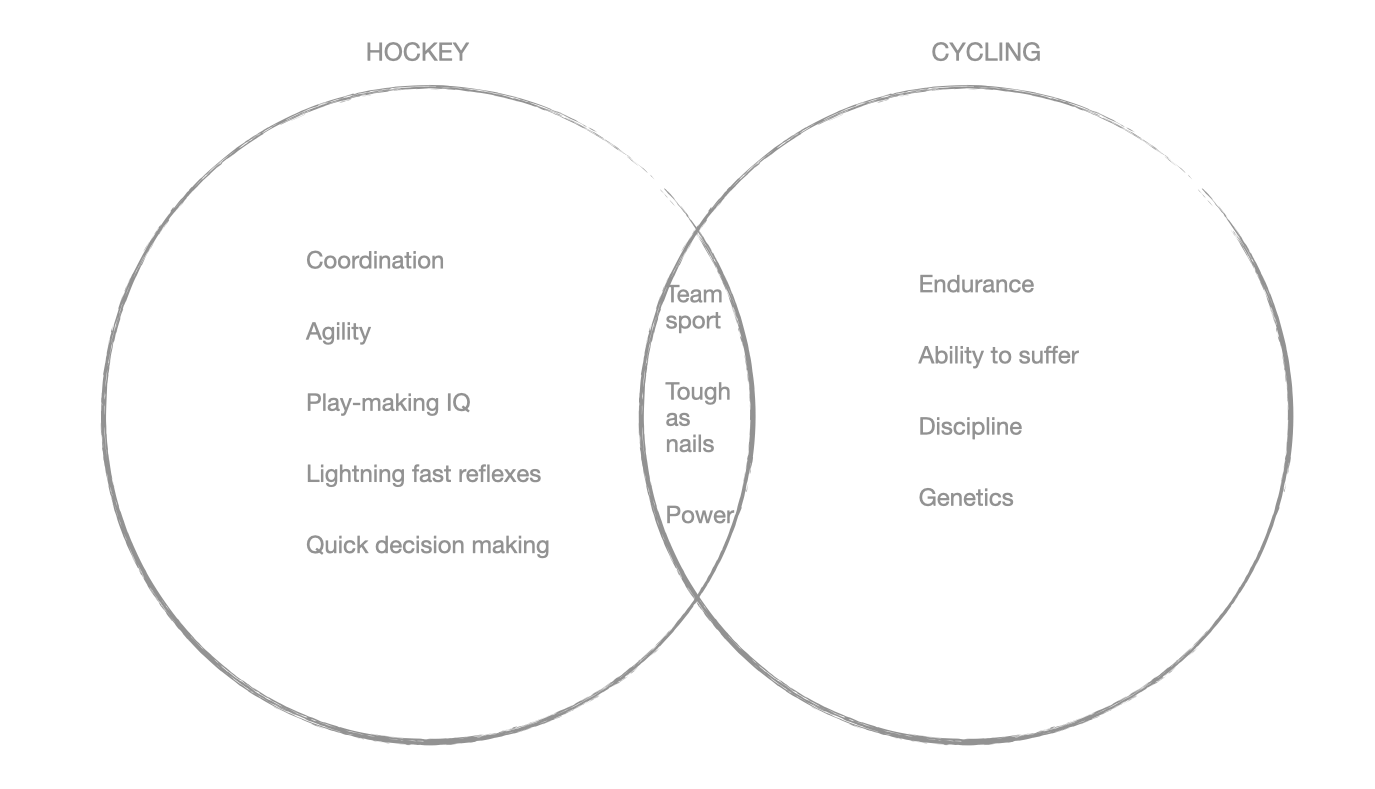

Road racing is a game of endurance, strategy, disciplined training, and – dare I use the trope – suffering. Hockey is a game of skill, coordination, play-making, and power. Both are very much team sports, but they couldn’t be on more opposite ends of the spectrum – and in my experience, they’re equally difficult in completely different ways. In a Venn diagram of attributes needed for each, there’s very little overlap.

Some of the attributes that come to mind:

If there’s such little overlap then why would Trek bring over their entire pro cycling team – both men and women –over to their HQ in Waterloo, Wisconsin to play ice hockey, you ask? I had the same question, so I spoke with the man responsible for this glorious fusion, Chad Brown, Trek’s CFO:

“We’ve had a hockey club at Trek since 2017. After we held the first World Cup cyclocross race, we were in our backyard at the factory. We were brainstorming what else could we do here? Wouldn’t it be fun if we put a rink out at the back of the factory and played lunchtime pickup hockey? So we built an outdoor rink and started playing pickup hockey.

“Over the course of two or three years, we would talk about it and publicise it inside the company. It began to gain some momentum three or four years ago at team camp. Jasper (Stuyven) and Eddie Theuns, Toms (Skujiņš) and a few other skaters said, ‘Hey, can we play hockey? Could we come and skate with you guys?’ Of course they can! And so they came out and we were amazed that anyone would want to come and play hockey with us. The next year before they came back, we’d get a text from the marketing team saying, ‘Hey, some more of the riders want to skate. Can you arrange it?’ We said, ‘Yeah, yeah, sure! Wow, so I guess it’s the thing now.”

What the Venn diagram above doesn’t punctuate is how important the team element of both sports are. Pro cyclists get the opportunity to hone their race teamwork for most of the year, but hockey brings totally different and complementary aspects of teamwork into cycling.

“From the outside, a lot of people think that cycling isn’t a team sport”, Brown says. “But in cycling, you’re only as good as your domestiques. You are not going to win the Tour without awesome domestiques. And no one’s gonna win the Stanley Cup without a strong third and fourth line. And if you look at both sports and it seems like they might be very individualistic, because you only see the highlights from, say, Connor McDavid … but you’ve got to remember, at the highest levels out of a 60-minute game, the best player in the world might only play 23 minutes. Just like a team that’s going to win Flanders. The leader of that team might only be at the front of the peloton for the last 30 k of a 200 k race. So, to me when we talk about hockey and cycling in the parallels, they’re both so deeply team sports.”

Another similarity between road racing and hockey is reading people and having that sixth sense for what shape the game or race is taking. Toms Skujiņš, who has been at the camp since the beginning, pointed out that “I think that awareness of how the team [in hockey] moves and awareness of how the peloton moves is quite similar. Trying to predict where people move in the peloton and where people will go next is kind of similar [to hockey] in that way. In team sports there are a lot of things that translate from one to another, and reading people’s body cues is a big one.”

After speaking with a few riders at the camp, it became obvious that there was something egalitarian about putting team leaders, veterans, and rookies (who are all extremely competitive) into a sport that most of them know nothing about.

Brodie Chapman, who is at her second Trek camp, says that“the most fun part with this team is the attitude. You have people who are really good [bike racers’ who’ve never been on the ice before and your cycling ability does not have any impact on it. So you’ll see some of the best riders in the peloton, with 20 years experience, holding on to the edge of the boards. And equally you’ll have some unexpected riders who perhaps ice skated before, like a lot of the Dutchies, who just seamlessly take to it.

“It’s definitely way outside my comfort zone. And I think being outside of your comfort zone with a bunch of new people or a bunch of people that you, you know, are teammates with, but you don’t see that often is just quite a nice icebreaker, excuse the pun. And yeah, you get to kind of be silly and no one’s judging each other. And there’s not really any rules.”

Speed skating is a popular sport in the Netherlands and many of the Dutch riders on Team Trek-Lidl skated as kids, eliminating one of the biggest barriers to entry with playing hockey. But it still isn’t easy.

Dutchman Koen de Kort is now Team Support Manager of Lidl-Trek, but as a previous rider for the team has played hockey at the camp many times now.

“It does get easier for sure,” De Kort says. “I remember the first time I played a couple of years ago. I would say I’m a good skater, but not with a hockey stick and a puck. So it was definitely a little difficult to start but I’m getting better now. I don’t seem to lose my feet when I’m near the puck anymore. The first day I was playing here with the employees I got in front of the goal and and tripped because I was looking at the puck too much.”

But that learning curve is still steep for riders who don’t have that background. Chapman, for instance, admits that playing hockey so infrequently isn’t enough to satisfy her competitive nature. The possible answer? A little extra ice time before camp.

“It’s not any easier the second time around, but there was a bit more of a quick transition from holding on to the side of the wall, to skating around the ice and learning how to change direction,” she says. “So actually, next year, the competitive part of me wants to go find an ice rink and practice before I get back here because it looks like it would be really fun to actually be involved and not be so scared of crashing on the ice!”

When asking around about who the best male and female hockey players are, the same ones come up again and again: Toms Skujiņš and Quinn Simmons. Both played as youngsters competitively in their youth until the bike came calling.

Skujiņš, who played as a goaltender in his youth, hails from Latvia where ponds and lakes freeze over in the winter and people naturally gravitate towards hockey. “I was 12 when a friend convinced me to finally try,” he said about his more formal hockey training. “We would take the train 40 minutes to Riga to practice together almost every day.”

“I played with some guys who are now on the national team playing in Swiss leagues. It’s quite cool to see now, especially this year when they won bronze at the World Championships.”

As for the women on Lidl-Trek, nobody I spoke to was aware of anyone who grew up playing hockey, although Ellen van Dijk started her career as a speed skater. After becoming a new mother last month she wasn’t at this year’s camp, but Lizzie Deignan’s positive attitude and leadership skills was mentioned to me multiple times.

“Lizzie’s confidence and enthusiasm gets her pretty far,” Chapman said. “She takes the hits and falls to the ground and really gets involved, and that makes her look like she’s pretty good at it. Actually, a lot of the women are much better than I expected just because I didn’t know any of them could skate.”

Chad Brown agrees about Deignan’s enthusiasm, and sees parallels with how it translates to cycling. “I randomly was skating past Lizzie, and one of the newer riders on the team made a comment like, ‘Oh, man, I’m going to be so horrible at this,’ And Lizzie said something like, ‘We don’t talk like that. We’re gonna be great. We’re gonna have a good time. Let’s go!’ She didn’t waste a second saying that this is not the language that we use on this team. And I felt like I just witnessed something great. That’s why she’s Lizzie Deignan, right? That’s why she’s one of the captains of that team.”

The parting (and loaded) question I asked everyone who I spoke to about this camp was about who would have an easier transition to the other sport to make: Hockey players to cyclists, or cyclist to hockey player? I didn’t think the answer was so simple (neither is well suited to the other, which is what makes this team camp activity so fantastic), but hockey player to cyclist was the unanimous answer. As Koen de Kort explained, “I’m pretty sure it’s easier for a hockey player to become a cyclist because [hockey] is such a skills-based sport. You need to at least have played as a kid to make it at hockey … [cycling] is pure endurance and almost then the other is just explosiveness; one is really skill-based and the other a lot less so. I think both ways, it’s gotta be pretty, pretty tough.”

As living proof, I can attest that a very average hockey player makes a very average cyclist. Which I’m okay with, because at my age I’m still loving both.

Now, wouldn’t a hockey match with Lidl-Trek vs Jumbo-Visma be a sight to see?

Did we do a good job with this story?