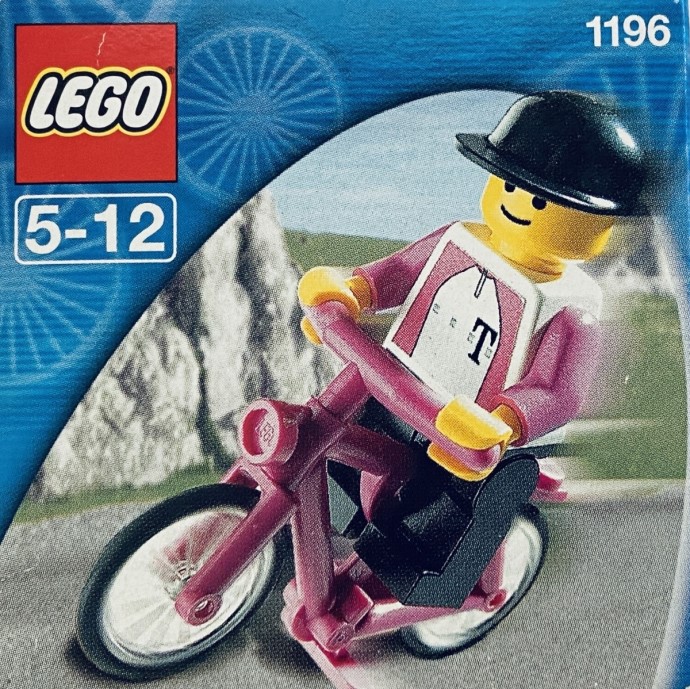

In the dawning days of a new millennium, Team Telekom had a Very Big Commercial Opportunity. No, not a TV commercial or other hazily defined brand exposure off the back of Jan Ullrich, Bjarne Riis, and Erik Zabel’s successes – we’re talking about a real cross-promotional extravaganza: a Team Telekom-branded Lego set.

Lego enthusiasts the world over could, just in time for the 2000 Tour de France, splash out on a four-part set designed by the Danish brick titan: with all the parts combined, there was a full suite of Team Telekom riders, classification winning jerseys and podiums, a team car, even a mechanic’s zone. It was, in the customary bricky structures and ever-smiling faces of the Lego world, an idealised version of a German cycling team that was still close to the top of its powers.

By that point, Jan Ullrich was reliably among the best GC riders in the world – but despite abundant talent and pharmaceutical assistance, the German’s tally of Tour wins would end at just one (1997), pushing him into the unhappy position of being Lance Armstrong’s eternal second. Heading into the 2000 Tour de France, though, most of that was in the future: he was a one-time winner up against two other one-time winners in Armstrong and Pantani, and the roads of France were set for a three-way showdown.

Weeks before that Tour – on 16 June, if we’re being precise, which we are – out came the Lego set. It would sit on shelves until 31 December, a heady run of six months and 15 days when blockheads could imagine themselves as Ullrich or his teammates. Initially, perhaps, the owners would dream of yellow and green jerseys for their Telekom charges. Zabel, at least, came through with the goods; for Ullrich, it was the first of a string of second places to Armstrong.

At some point during the pandemic – from memory around when I was writing about bad Danish mix CDs – my colleague Matt pointed me to the existence of this Lego set for the first time, and it’s fair to say it made an impression. Together we looked into the cost of picking some up on Ebay (surprisingly expensive) and pondered how to unthread its narrative backstory. I must have remembered about it at some point since, because the other day I found an open browser tab with a clue. [Yes, obviously I have a chaotic desktop and browser.]

That tab contained a page from the gloriously nerdy and extremely thorough BrickSet.com (“the primary reference on LEGO sets on the internet”), which seems to be one of those rare places online that is both entirely wholesome and useful. All the best bits of internet culture seem to be here: deep interest in something niche, creating a gathering place for 320,000 members owning a combined 15 billion pieces of Lego. In addition to all the technical data of the Team Telekom set, right down to barcode numbers and box dimensions and fractions of grams, was a name: Bjarke Lykke Madsen, a Danish-sounding Dane credited as the set’s designer.

I didn’t get as far as I might’ve hoped in tracking down Madsen – sadly (sensibly?) he has not responded to my messages on Instagram or Facebook – but I think there are things we can learn about him nonetheless. In his role at Lego, Madsen seems to have found a unique combination of passion and profession. Crucially for our purposes of finding out the backstory of a 25-year-old promotional Lego set, he’s also an enthusiastic contributor to BrickSet, providing generous notes for all 137 sets he personally designed.

In his bio Madsen has, he says, been a designer for the Lego group for more than 26 years. A childhood fan of Lego, he studied as a machinist and mechanical engineer before scoring a dream gig as a Lego designer in August 1997. While he’s credited as the designer of the Telekom set, he’s keen to stress that bringing any Lego product to market is a collaborative process involving “hundreds of LEGO employees in many different departments: Design, Marketing, Building Instruction, Production, Packaging, Distribution and more. The goal is to make each LEGO set the best possible building- and play experience for our customers, and it only becomes possible, because everyone is working together to achieve this.”

He signs off with the hope that his work “will be interesting to kids, parents, newcomers and longtime fans. Enjoy & kind greetings – Bjarke :)”

I’d hoped for the origin story of the Team Telekom Lego set, but had stumbled across something much more intriguing: the process of how it was made, directly from the designer. After receiving the brief, Madsen “built an entire environment/landscape of stuff all related to the bicycle race” which was then divided up into the four constituent sets (1196-1199). Once those sets were combined, consumers “would get a complete bicycle race team including nine riders on nine bicycles all in the same dark Pink colour scheme [ed. alas, Lego-branded, not Pinarello], with the option to switch some of them out for the lead shirts.”

For Madsen, there’s no immediately evident nostalgia for the Telekom set, unlike his first-ever product which went on sale a year earlier (“I had my first official LEGO set done only five weeks after I started. Not even in my wildest dreams, would I had believed that to be possible,” he writes of 6459-1: Fire Truck). But he reserves some affection for the work of the graphic designer, Kim Yde Larsen, that he collaborated with on the packaging: “I like the mountains in the background of the packaging a lot.” Looking at the gritty scans of the boxes, I agree with him.

The best part of a quarter century on from Team Telekom’s Lego set, much has changed. Bjarke Lykke Madsen seems to have left Lego, but not before getting an IMDB credit on the art department of The Lego Movie. Team Telekom is gone, its name associated with a darker era of the sport and with fallout so severe it severely harmed the sport’s standing in Germany for years. Ullrich has had many public troubles, spent time in a psychiatric hospital and sobered up; Riis has left the sport for good and is now importing heat pumps from Lithuania. Perhaps the clearest sign of the passage of time is the fact that Erik Zabel’s son, Rick, is now something of a veteran of the sport, 10 years into a pro career of his own.

Time moves on, sure. But like cycling, there’s simultaneously something timeless about this old piece of promotional curiosity – Lego figures that haven’t changed for years, navigating a world of play, with an avid market of collectors that are still hunting for them. The escapism that Lego brings to its owners has its own parallels to cycling; freedom, imagination, exploration. For a brief, glorious window in 2000, these two worlds collided.

Did we do a good job with this story?