Hidden behind their lenses, usually buried amongst the chaos of the race, are the photographers of the Tour de France.

Television viewers will often see them hurtling along on motorbikes ahead of the riders, snapping away, or temporarily dismounted and clicking their shutter as the peloton zips past, but that is only a fraction of the battalion of accredited professionals on Tour, armed with a camera and ready to document the race in still frame.

For us on the other side of the race’s accompanying media, who spend days sitting in press rooms, sometimes barely seeing the race in the flesh, the photographers are ethereal beings. A quick hello at the stage start as they quickly grab a coffee before heading out onto the course, and later arriving at the press room sweaty and exhausted. In one respect, they are the media’s equivalent of football goalkeepers: you’d have to be mad to be one.

To uncover the method and the madness of the Tour’s photographers, at the 2023 Tour de France I spent the day with two of them, Chris Auld and Zac Williams, on stage 19 from Moirans-en-Montagne to Poligny, won by Matej Mohorič.

Depart – 172.8 km to go

Instead of heading to the start village as normal with Escape Collective colleague Iain Treloar and Joshua Robinson of The Wall Street Journal to ask the beleaguered employees of the Senseo stand to pour us all a cappuccino for the 19th time this Tour, or to the mixed zone to hear another rider tell me how they’re going to see how today’s stage goes before offering a non-opinion on it after the fact too, I head to the car park. Specifically, parking avant, which translates roughly to parking before, meaning your car has to leave said car park and get out onto the course before the start of the race or the French gendarmes will gendarme you all the way to hell and back.

Chris is already sat in the Mercedes Sprinter van and I slide the passenger door open to take my spot in the back amidst mounds of clothing, equipment, and bikes. Zac and Chris, along with fellow photographers New Zealander Harry Talbot and Brit Russ Ellis, camp throughout the Tour. Yes, in tents. This keeps costs down (don’t get any ideas, Caley), affords them time in the mornings to head straight out for bike rides (please, Caley, no camping), and likely makes it feel a lot more like Lads On Tour than an Ibis Budget ever could.

The three of us all seem quite excited for a day that’s different to the previous 18. For me, the chance to see more of the race than I otherwise would have; for Chris and Zac, the chance to show one of their ignorant colleagues just what goes into getting the photos we use in our silly little articles.

Motorbike spots are highly coveted and have to be shared by the entire photographer corps at the race. There are only a few photography bikes within the Tour cavalcade, and L’Équipe get a dedicated one (of course) as well as one for the agency photographers (think big, serious news organisations like Agence France-Presse) on – I believe – a rotating arrangement. But the rest might get one or two days on a moto. Or often none at all. For them, life at the Tour means being master of your own destiny and trying to get yourself as close as possible to the peloton as many times as you can. Day in, day out.

In the car, Chris and Zac immediately begin scanning a map of the route on their phone.

“The first cut can be wherever you want it to be, if it’s shite, it’s shite,” Zac says, having gathered some intelligence in the start village from other photographers, or what Chris refers to as his morning gossiping. The Labrador-esque energy of Aussie Williams and the dour Geordie-ness of Auld makes for a sitcom duo. In fact, I should pitch that to them this summer.

“Everyone is saying 2-3 stops,” Zac adds. “Two if it’s shit, three if it’s alright.”

By this point in the Tour, when most have become exhausted of the circus and are ready for home, the expectations for a good day out are low, and therefore it’s hard to be disappointed. A mental trick to retain sanity.

Those who write articles or make podcasts can correct mistakes afterwards. They can edit drafts, take notes to refer to when recording, or re-watch a crucial moment on replay to make sure they got the facts right and didn’t miss anything. For the photographers, however, once the race is done that’s it. No more photos that matter.

As we roll out through the start town there are flags lining the street but the angles are wrong, they tell me, Chris cranes his neck around while keeping one eye on the road, looking for a possible vantage point.

“That’s the cut, it’s quite clean there,” Williams offers. Chris turns his head to check the shot, framing it in his mind.

There is point in being picky. “You’d rather have one amazing shot than four average ones,” they add, but that’s the thinking from the part of their brain that is photographers as artists, not photographers with clients to please.

Chris, established as one of the best in the business alongside the aforementioned Ellis, have a business together, with a multitude of clients ranging from riders and teams to sponsors, all of whom want nice photos to show off the riders wearing said sponsors.

Orgelet – 123 km to go

We go through a nice-enough village containing some flags and some open barn doors right next to the road.

“It’s alright, it’s not amazing,” Zac says.

“There’s potential here,” Chris agrees.

“I like that,” adds Zac, pointing at a painted sign on the wall, an old Forvil cosmetics advert that screams quintessential small-town France.

“Barriers there, though,” Chris qualifies.

We park the van up and hop out onto the course. The roadside spectators, who have already been waiting for a while and are desperate for something to occupy them, take a small interest in these people who have rocked up 10 minutes before the arrival of the peloton and get to sit on the other side of the barrier – on the actual course.

Léon van Bon also soon turns up, and if that’s a name you recognise it’s because yes, that is the same Léon van Bon who won two stages of the Tour de France and a silver medal in the points race at the 1992 Olympics.

As he greets us Chris asks him for advice on how exactly the riders will come around the corner, so he can fine-tune his shot. Later they tell me that Van Bon gets recognised often, and doesn’t necessarily lap up the adulation. He’s there in his second career act, trying to get his own best shots possible and needs minimal other distraction from the job at hand.

Soon the red ASO race car and accompanying police cavalcade are past, before a cheer rises up around the corner from us – signalling that the race has arrived.

Matteo Trentin is leading a small move off the front and gets chopped by the TV motorbike, whose driver has mis-judged the angle of the corner. Trentin cries out in alarm but remains upright. The riders are soon through safely. Chris and Zac are done “spraying and praying,” as they self-deprecatingly call the frantic clicking of the shutter as the race zooms past, and we walk back down the road. Van Bon is already in his car and off to his next spot. “Léon van Gone” is apparently his nickname, the speed of his work staying true from one career to the next.

Later, Zac uploads the shots from the corner in his daily Tour post:

When we get back to the car, a secret of the cycling photographer world is revealed to me: when you are situated in a corner like that, you are kind of hoping for a crash.

Not in a mentally-willing-the-riders-to-go-down kind of way, but crashes are inevitable and better they happen in front of people professionally ready to document the incident than in a vacuum of French countryside where the only record is the rider’s sworn testament.

Before you sharpen your pitchforks, decrying how a presumed-noble endeavour of cycling photography is merely a masquerade for this ambulance-chasing cabal of jackals, understand that a quirk of the peloton is that the riders always want their own crash photos.

“It’s better to just give them the photo than get €20 as you never know where it can lead you,” Chris says. “You’re always looking for your break.”

The lucky break is a central part of being a cycling photographer.

In a previous life, Chris was a studio photographer before the bottom fell out of that particular market. So, because he liked cycling, he started shooting the British domestic scene and then did his first WorldTour race in 2016. Now, a bunch of clients pay him (and Russ) a retainer each month for the use of their photos, with December the crucial renewal month to make the whole thing viable for the next season.

“You always have the pressure to shoot,” Chris says. “Always trying to deliver maximum value to the client.”

Chris’ lucky break is likely a photo you’ve seen before. Stage 2 of the Tour de France 2017, the peloton are making their way around a slippy corner en route to Liège from Düsseldorf when bam: Chris Froome, Romain Bardet, the yellow jersey Geraint Thomas, plus many more, all hit the deck, sliding straight towards Chris. A gendarme had the foresight to move him slightly on that corner, otherwise Chris Froome would have ended up in his lap. It’s a phenomenal scene.

This photo, this lucky break, wasn’t necessarily something Chris thought you needed to really level up your career, but a shot like this gets your name out there. It means you become a name. The guy who got that shot that everybody knows.

“Zac’s lucky break was meeting me,” Chris then adds, joking.

The 24-year-old, 6 foot 5 or more, Zac looms over most people, which would be intimidating were it not for the wide grin he is usually wearing and his easygoing manner. In a similar way to how neo-pros today say they looked up to Chris Froome and his generation as juniors, making everyone who was around as adults for the Froome era feel exceptionally old, Zac says he looked up to Chris (Auld), Russ, and the Grubers before meeting Chris at the Tour Down Under one year.

“A big thing in the industry is earning your stripes, by being at races and working hard,” Zac says of the prove-yourself mindset of his corner of the industrial-cycling complex. In between stories, Zac is navigating and Chris is driving at a fast (and legal) speed.

They are constantly scanning for good spots to stop and take photos. Although, there is another way to do this. The Grubers, husband and wife team Jered and Ashley, revered to an almost demigod status by their peers and the wider cycling world, will spend their downtime painstakingly reconning more kilometres of future race routes on Google Street View than would prove sane under psychological supervision, all to have a slight head start when they arrive at that morning’s stage knowing where they are headed.

In between all of these stories, Zac’s head bobs up to look at the road and then back down again to consult his phone’s map, an ongoing calibration. Yes, that’s that turning we were looking at, but too many people there. There’s supposed to be an exit around the next corner that would allow us to get off course and add in an extra stop but someone has put barriers up, contradicting the instructions. “The barriers can make or break your day,” they tell me.

It’s a constant battle with your own anxiety. If we stop too early at an “okay” spot, the worry is will there be a better one just around the corner? (Yes, there will be, and is apparently a law of nature of shooting a bike race). If we don’t stop at this serviceable spot will that be it for the rest of the stage and we’ll arrive at the finish line with … nothing? “The best spots to shoot are the ones you didn’t get to,” Chris says. Any in particular stand out from this race? “The rollout in Bilbao,” where the Basque fans started as they meant to go on with their general madness and deep love of the sport. Regrets pile up on top of regrets. Who’d be a race photographer?!

Crotenay – 65 km to go

After heading out in the morning you have your first stop of the day ahead of the race, a contrasting moment of calm before the peloton and fleets of vehicles arrive. But after that stop, a different problem arises: how to get back in front of the race.

Once behind the peloton, you’re in your own race and, vexingly, usually stuck behind the van that stops every few dozen metres to take down the race’s directional signs. You are not allowed past this van, by order of the motorbiked gendarmes, even if once you get ahead of it you would be out of their way forever. It is an impossibly frustrating set of working conditions – and this is what Chris and Zac deal with every single day.

The only way through is around. Eventually we find a turn so we can get off course and overtake the race, get back on course, and find another spot to shoot.

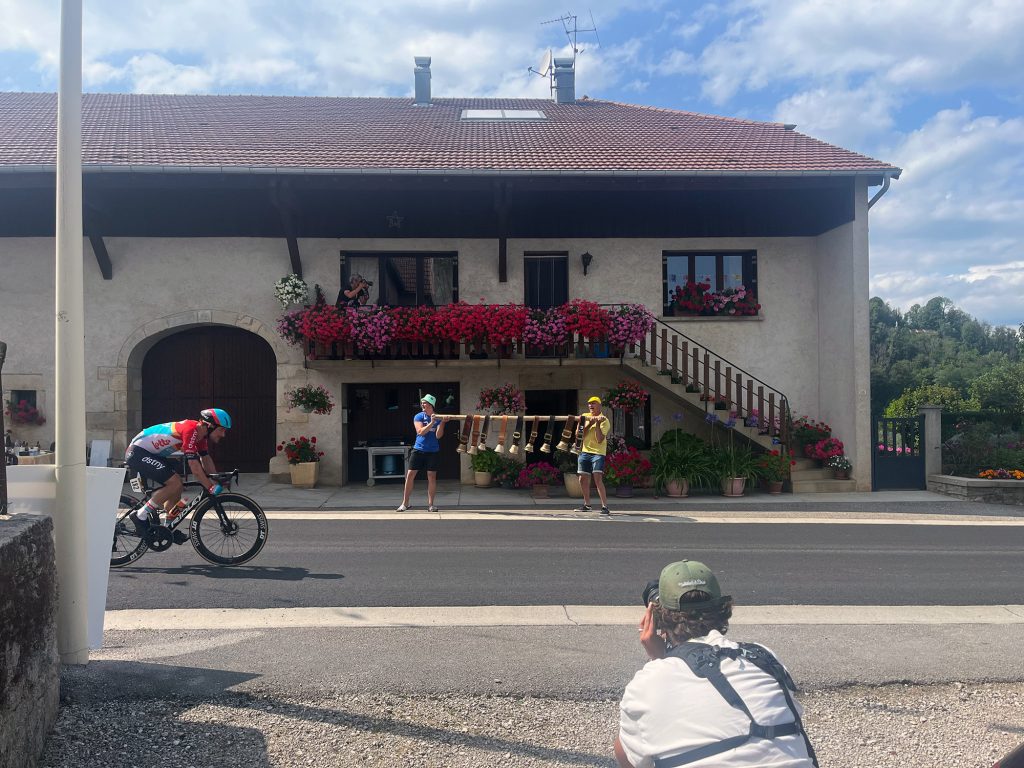

We come across an idyllic French village. There is a long street of well-appointed houses, blooming with summer-time flowers and foliage. There are two men preparing to lift up a heavy stick bedecked with bells. This is the spot.

“The photos from the Tour have to feel like they’re at the Tour; you find a shabby wall or a nice door,” the boys say, continuing with their education of how to shoot the Tour.

They walk up the road to choose their exact shot. Chris takes a family’s photo for them. “Usually you don’t do that as the next thing they ask is how can they get the photo …” and then it becomes a whole thing while you’re just trying to take some photos of bike riders.

There’s a barn filled with ancient machinery and cart wheels. Chris dives inside to test out the angles, envisaging how the riders will frame when they pass by in a few minutes. It’s not quite right, so the search continues.

We head back to the house with the balcony of flowers and the bell boys beneath. Chris starts on the balcony and Zac the other side of the road as the breakaway passes, before a gap in the race allows them to switch sides to shoot the other angle.

It’s now a guessing game as to whether the yellow jersey group was in fact the peloton, and the rest of the race will be coming past in dribs and drabs over the next 10 minutes. After some deliberation it’s decided that was the main thrust of the race, so we head back towards the van in order to make as speedy a getaway as possible when the broom wagon passes and we’re allowed back onto the route.

Flamme rouge

Back on the course, we need to find a turn-off so we can cut cross-country and make it to the finish before the riders do. An added difficulty this year, as became a slight moral panic in the French press and on television coverage, is that the roadside fans are more … let’s say dynamic, or boisterous, than usual, which is something Chris and Zac say they have certainly seen out on the road.

There’s a van parked across one turn and cars filling another, but right at the end of the blockage there’s a small gap to squeeze through; the juxtaposition of needing to very slowly, very carefully, drive through a tiny hole while concurrently being in a massive rush cannot be good for your cortisol levels.

We’re now driving fast (again, legally fast) down small country roads but cars keep coming from the other direction slowing us down. “This is the busiest road in France,” the pair lament. It probably is.

When the race envelope (the distance between the front group of riders and the broom wagon) gets too big, it makes it extremely difficult to catch up.

“Sometimes the finish line is the race,” Zac explains of the importance of getting to the end before the riders. “In a sprint that’s the case and you’re tapped in the head if you don’t go to the finish on a sprint day.”

“Or the [Col de la] Loze stage,” Zac offers as a counter-example. “The finish line [where Felix Gall won] didn’t necessarily matter that much, but if Vingegaard had won the stage it would have been the photo of the Tour.”

We get to the finish and we part ways, with Chris and Zac going one way nearer to the finish line and myself heading about 200 m past it in order to try and catch riders for post-race grabs following the race.

Mohorič wins and is overcome with emotion, a moment Zac captures visually (as you can see in his Instagram post near the start of this article) and our Kate Wagner records literarily.

When I eventually get to the press room, about three or four hours after the time I’m used to doing so, I am beyond starving. Now I get to experience one of the biggest bugbears of the photographer corps – the press buffet has been ransacked by the time they turn up. The watered and fed written media is slumped at their desks, lazily filing copy while digesting the bread, cheese, and wine that helped pass the time mid-stage, and now the photographers, who by comparison have been out sweating for five hours, have been left with nothing.

Zac and Chris eventually enter today’s designated gymnasium-turned-press-room, and set about editing and uploading their photos.

Jonas Vingegaard completes his yellow jersey press conference, and of course by this stage is pretty exhausted physically and tired mentally of fielding mostly similar questions every day, and does well to bat most away with non-answers, which causes Zac to burst out laughing, beholding that this is how the written press spend their days.

The big question for the pair that I’ve spent the day with: in terms of a day out shooting the Tour, how did that one rate out of 10?

“4/10,” is Zac’s estimation. “5/10 in terms of photos,” answers Chris. One can only presume that stipulation is because the company of Zac and myself has been 10/10 …

Escape Collective boss Caley wanders over to ask how our day went, and to see some photos.

Chris, whose default setting is effing and jeffing, has one particular photo he’d like to show and supplement with a final eff and jeff for the day.

So, that nice town of our second spot, which we’d fought tooth and nail to get too, carefully picking out the best vantage point to get a cracking shot, shooting over the flowers with a church in the background and fans cheering on the road? A TV motorbike was filming the group as they passed, getting in the way of the shot and bursting the magic Tour bubble that the scene otherwise depicted. That, I’m told, is the perfect summary of a day in the life as a Tour photographer.

Part of being in the Tour bubble is complaining about the rigid infrastructure, the maddening rules that make no sense that still must be followed. The venting of frustration is a cathartic release for the pressure to take photos that you are both proud of and that your clients will like.

Beneath it all, however, there is a deep love for not just the Tour, but of being on the road, of being as close as you can get to the race without being part of a team or ASO, of living a life very few get to, of playing your part in preserving the memory of halcyon summer days in France.

Chris Auld’s work can be found on his website and on his Instagram.

Zac Williams’ work can be found on his Instagram.

Did we do a good job with this story?