Stage 9 of the 2023 Giro d’Italia was a nailbiter. Remco Evenepoel, dominant in the opening-stage TT, eked out the narrowest of wins over Geraint Thomas: just one second separated them, with Thomas’ teammate Tao Geoghegan Hart another second back in third. Although Evenepoel would hours later test positive for COVID-19 – suggesting that his physical condition was far from optimal – the close margin underlines how narrow the gap can be in TTs.

The old adage about time trials is that they’re the “race of truth”: a pure test of strength with no tactics and no teammates, just rider versus rider and rider versus the clock, may the fastest win. But what if there’s a thumb on the scale? One that’s technically available to all, but in practice is employed unevenly? We’ve known since 2015 that team cars following riders can affect aerodynamics, and for 2023 the UCI changed its rules to require team cars to keep a 25-meter distance from riders in time trials.

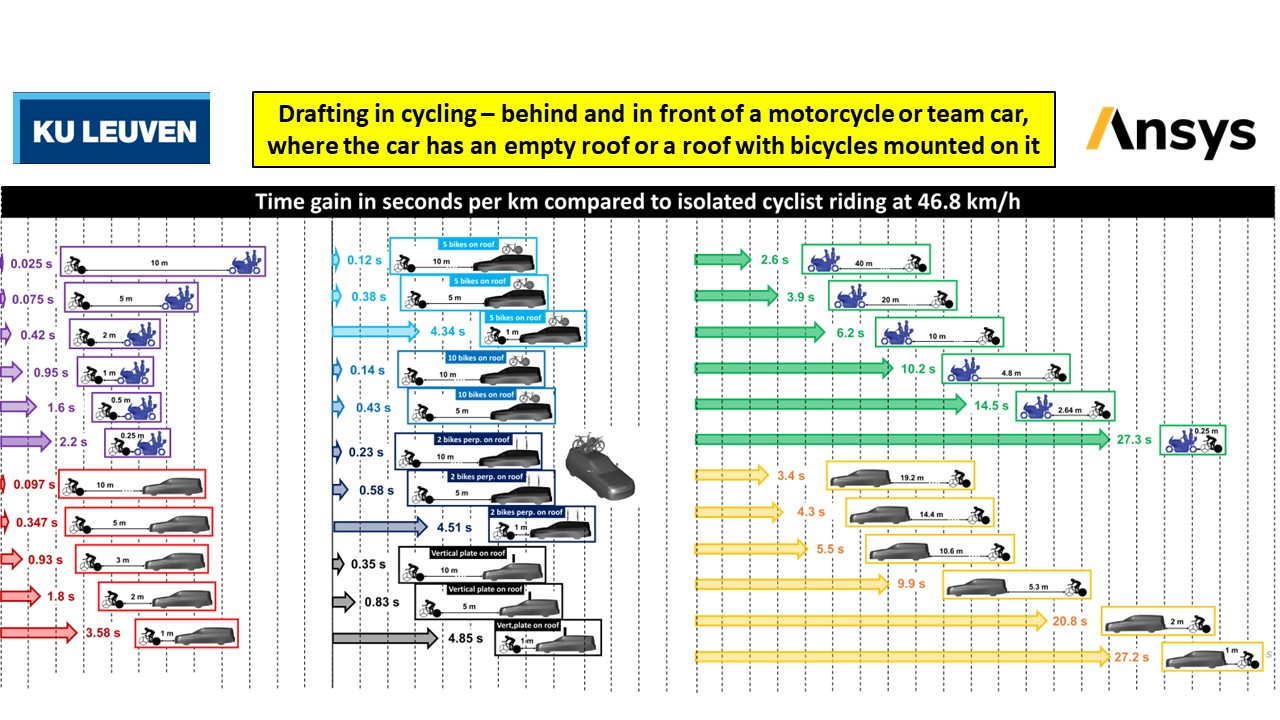

New research by Bert Blocken, an engineering professor at KU Leuven and aerodynamics consultant for Jumbo-Visma, suggests something more: that even at a given follow distance, aerodynamic benefit from the follow car can vary in small but significant ways depending on the number and arrangement of spare bikes on top. Ahead of the only time trial in the 2023 Tour de France, and with the top two riders on GC separated by just a handful of seconds, even minute details matter.

“Last year, we saw Filippo Ganna riding in Tirreno-Adriatico with a follow car with at least 10 bicycles on the roof, and I wondered what difference that would make,” Blocken told Escape Collective. Blocken has done lots of research on the effect of cars and motos in the convoy, including that original 2015 paper, but there was no scientific data on what was on the roof. So he decided to follow up.

Blocken used quantitative modeling tools from Ansys, a maker of engineering simulation software, validated by wind-tunnel data, to examine the aero effect of a variety of spare bike arrangements. The resulting research product is a draft; the methods, data, and conclusions have not yet been subject to formal peer review or informal scientific scrutiny through open-access publication on a platform like arXiv (Blocken says he plans to publish the paper himself on Monday). But as Ineos’ use of bikes for Ganna shows, teams already know and employ some of what he found: the more bikes on the roof, the bigger the push draft.

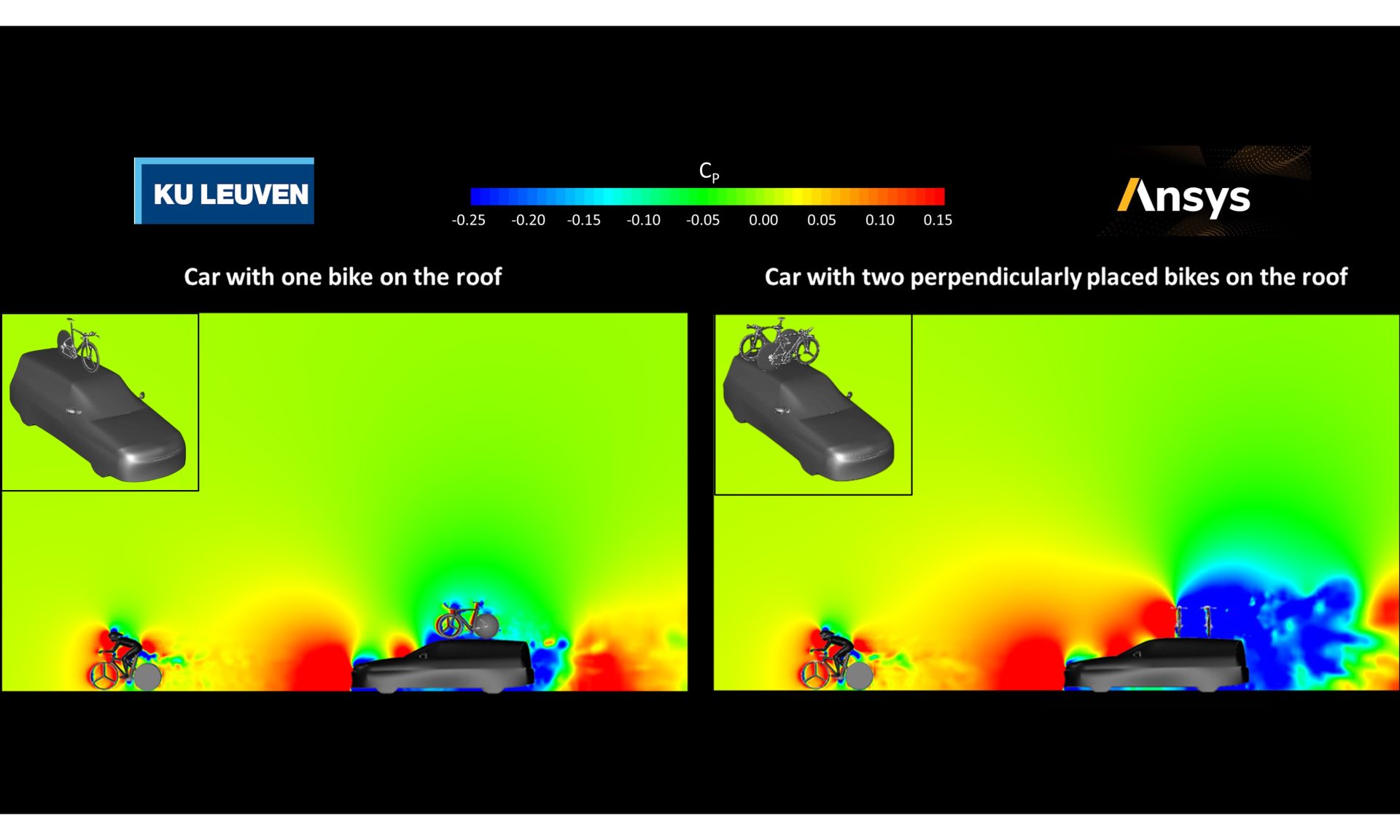

“Bicycles are designed to be as aerodynamic as possible,” notes Blocken. “So it will not give a large push effect, and indeed that’s what we find with one bicycle.” But when you multiply them, it effectively creates a kind of wall. Ganna and Ineos weren't ensuring against multiple mechanicals by following him in a car bristling with a team's worth of bikes; they were likely looking for a boost.

Here’s how it works: any object in motion has an aerodynamic profile – it has to push through the air, and in doing so creates an area of higher pressure relative to ambient conditions, called an overpressure zone – the opposite of the lower, or underpressure zone, that follows in its wake. The combined effect of those zones on the object's velocity is what we know as drag. The larger and blunter the frontal surface area, the larger and more pronounced is that area of higher pressure in front. That overpressure zone helps to “push” any object in front of it, and the closer they are to each other, the larger the effect. Take a vehicle with a large overpressure zone and put it closely behind a rider (10 meters or less, although the effect is still measurable at 25 meters) and it minimizes the rider's own underpressure zone, giving them a push draft.

That’s why the UCI (finally) changed the rules last year to a minimum 25-meter follow distance in time trials. In practice, the enforced gap is often far less. The time differences on a World Championship-length TT course ridden at elite speeds can be small, sometimes amounting to just a few seconds. But that might be enough to change a result.

Stage 9 of the 2023 Giro was not exactly an outlier in respect to closely contested time trials; last year’s World Time Trial Championship was decided by a three-second margin from winner Tobias Foss to Stefan Küng, and in 2021 Ganna vanquished Wout van Aert by six seconds, while Ellen van Dijk beat Marlen Reusser by 10 seconds. That same year, the silver medal at the Tokyo Olympics came down to three seconds for the men and six for the women. Rainbow jerseys, race leader’s jerseys, Olympic medals, and stage wins – all career-defining achievements – turn on the tiniest of differences.

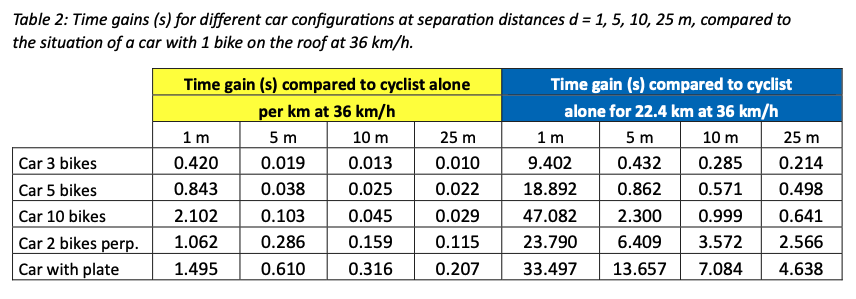

You’ll notice something in that graphic above: one of the biggest push effects comes not from the number of bikes on the roof, but how they’re oriented. If you take just two bikes, and mount them sideways on the rack, all those forward-facing aero features like airfoil tubes and disc wheels become a big air dam, creating a large overpressure zone compared to conventionally oriented bikes. “If you go to the extreme of putting 10 bikes on the roof, then it’s a small step to just put (two) perpendicular” says Blocken, who adds he’s surprised we haven’t seen teams try it yet.

That’s partly why Blocken is releasing his data before the Tour’s only time trial, and why he created two estimates of the benefit, at an expected average speed of 54 km/h as on a flat course, and 36 km/h to reflect the climb at the end of stage 16.

As the data show, the modeled effects are largest with close follow distances and decrease significantly at 10 meters, although they're still measurable at 25 meters. Since that’s the mandated follow distance, and the perpendicular bike hack is not illegal and technically available to all teams, why the fuss?

For starters, awareness on teams is not uniform; as one of the graphics in the paper shows, while Ganna and Remco Evenepoel made use of an overstuffed roof rack in that 2022 Tirreno TT, Tadej Pogačar’s UAE follow car had just two bikes on the roof in normal orientation (Pogačar finished third, 0:18 down to Ganna and 0:07 behind Evenepoel over 13.9 km). As for mounting bikes sideways, the roof racks on follow cars are typically custom made; modifying them to run bikes sideways would take advanced planning, as well as resources that smaller teams might not have.

As well, the 25-meter follow distance rule has not been well-enforced this season. There aren’t enough regulators, commissaires, and TV cameras to monitor every rider on course, although the stage and GC favorites are usually well-covered. Finally, there’s always the chance that a young emerging talent never really gets a chance to show herself because aero tricks from better-resourced teams consistently prevent her from taking a big result that leads to a career-making contract.

Blocken’s solution is relatively simple: more closely monitor the 25-meter follow distance, and restrict all follow cars to two bikes on the roof, oriented in the normal direction. He’s presented his research to the UCI and says that Michael Rogers, the ex-pro and three-time world time trial champion who is now the governing body’s head of innovation, has been generally receptive to his findings, although Blocken added he had no expectation of any rules tweaks before Tuesday’s time trial.

That’s where the sport is now: the big, easy aerodynamic gains are all gone. Teams and riders search for 10ths of a percent advantage: the way a skinsuit’s seams are aligned, or the difference between custom-made TT handlebar extensions and fast-but-off-the-shelf options. Gaining a small boost from how bikes are placed on the car roof is a logical step, if it's allowed.

After 15 stages of the 2023 Tour de France, and 62 hours and 34 minutes of action on the road, yellow-jersey-wearer Jonas Vingegaard leads Tadej Pogačar by all of 10 seconds. They're evenly matched, and a time trial might be a tantalizing showdown. Blocken’s proposition is simple: do we want that decided on the road, or because a team packed a roof rack full of spare bicycles and drove a little too close behind their leader?

Did we do a good job with this story?