It feels like every few weeks we hear of yet another iconic mountain bike brand expanding into the dropbar world with a gravel bike. In fact, you could have been in a horrific hedge-trimming accident and still have enough fingers to count the number of medium-sized mountain bike brands that haven’t at least dabbled in having their name on a gravel bike.

This article looks at why even the most hardcore and focussed of mountain bike brands, even brands that don’t do cross-country bikes, are getting into bikes with curly-whirly bars. And spoiler: it’s because there’s money to be made.

The state of play

Before we get to the recent spate of newcomers to drop bars, it’s worth noting that specialist mountain bike brands dabbling in gravel is nothing new. After all, gravel is about riding off-road. And in fact, the origins of modern gravel riding were founded on people converting cyclocross bikes and mountain bikes to the purpose.

Indeed, some mountain bike brands were there from the beginning when gravel was just a twinkle in the eye of the broader industry. One such example is the once-29er mountain bike specialist, Niner, which introduced its first disc-equipped gravel bike a whole decade ago. At this time, you already had the likes of Salsa Cycles spearheading the movement to replace the converted mountain bikes of early adopters, and as always, there were quite a few custom framemakers fulfilling specific requests.

With cyclocross still in craze, it can be tricky to decipher the specific timelines for when some of the earlier adopters got their start in gravel. For example, Santa Cruz resurrected its Stigmata in 2015, but marketed it as a modern cyclocross bike that owners could put fatter tyres on. That was a common trend then, with cyclocross bike sales booming, but many not seeing any race action between the tape.

Now keep in mind that Cannondale’s Slate is often credited for being at the forefront of the gravel boom – a bike that was released in 2016 – and it’s clear that a small handful of mountain bike brands were there before. However, when Cannondale threw its weight behind that quirky Slate, we soon saw other brands bring out their vision for gravel. Specialized, Trek, and Giant all followed suit before a number of second-tier brands made the investment, too.

Even pre-COVID the gravel world was booming (at least in the United States), roadies were going off-road, and mountain bikers were finding the joys of mile-crunching through gravel bikes, too.

“More mountain bikers and road riders [are] choosing a gravel bike as a secondary ride, said Santa Cruz Bicycles’ brand marketing manager, Scott Turner.

“For mountain bike riders, [a gravel bike] is their ‘road bike’ and a way to get out, have fun, and go fast on trails that may be a little less challenging than what they use their mountain bike for, and for long-distance exploring. For road riders, it’s a way to get off the road and still have that racy drop bar feeling, race gravel events, and for that same long-distance exploring.”

And with this consumer demand, it makes sense that in recent years we've seen interest in the gravel market from some truly hardcore and previously gravity-focussed brands.

Best known for its dirt jump bikes, NS Bikes launched an entire offshoot gravel brand in 2017 – Rondo. The bikes introduced geometry-adjust flip chips, then already common in mountain bikes, and aimed to bring a different perspective to gravel bikes. The NS brand also offers gravel bikes, while Rondo continues to push the technology envelope.

In 2019 came BMC’s first dedicated effort in gravel, and while admittedly not a mountain bike-focussed brand, the Swiss company took a mountain bike focus to its first gravel bike. The URS brought to gravel the longer front-centres, short stems, and slacker head-angles associated with modern mountain bikes. This was a pivotal bike, and arguably one that got many thinking past the idea of using road-inspired and UCI-approved geometry.

Another extreme example of this step-change in gravel interest came from Evil Cycles, a gravity-focussed bike brand that had previously shown zero interest in cross-country, let alone drop bar bikes. Evil’s introduction to gravel with its Chamois Hagar was so extreme it was almost a poorly timed April Fool's release, and it sought to bring across popular progressive geometry concepts from its mountain bikes. Three years on and the Chamois Hagar is still the most slacked-out gravel bike readily available for purchase. And to be clear, I still don’t really understand this bike (and yes, I've tested it previously).

Sprinkled out over the past few years we’ve seen a handful of other once-MTB-only brands expand their horizons. This includes the likes of Pivot, Orange, Devinci, and Nukeproof all adding a gravel bike to their ranges. And indeed, there are many other examples I could add to this list.

And then, finally, we get to the list of newcomers that inspired this article.

In late 2022, large German consumer-direct and gravity-focussed company, YT, was another to throw its flat-brim cap into the circle with a suspended gravel bike. Like Evil, YT was a company that hadn’t glanced sideways at the cross-country market, but here it was, leap-frogging into the gravel world. And in 2023 things have just gone bonkers with a series of baggy-wearing brands squeezing into lycra (or baggies, it’s your call).

Colorado-brand Why Cycles announced it was done being a seperate brand from sibling mountain bike company Revel, and so you can now buy a Revel gravel bike. Rocky Mountain released its Solo gravel bike. The aluminium-focussed gravity brand from Andorra, Commencal, surprised many with its 365 gravel bike (including an aluminium fork!). Mondraker and Rotwild, two prominent European mountain bike brands, have both launched e-gravel bikes. And then a few weeks ago, Intense Cycles quietly announced its entry with the price-point-focussed 951 series (a series you can purchase through Costco.com of all places).

That is now a significantly long list of once hardcore mountain bike-focused brands that are no longer solely focused on mountain bikes. So who hasn’t unravelled their focus for gravel?

Sticking with mountain bikes

Look to the biggest of big names in the industry and you probably won’t find a single one without a gravel bike today. That’s quite the stampede of uptake when you consider the first edition of Unbound Gravel (then called Dirty Kanza, and certainly far from the first gravel race) was run in 2006 with 34 participants; a whopping 3,775 lined up in 2023.

There are, however, a few notable examples when you look at some of the more mid-sized mountain bike brands. What’s a mid-size brand? Well, it’s hard to quantity, but I’d say road equivalents would be brands such as De Rosa and Basso.

Propain and Forbidden are two gravity-focussed brands that are yet to make the jump. Situated in the Pacific Northwest of the United States, Transition also doesn’t offer a gravel bike, but it did offer a cyclocross bike in 2014. According to Transition's marketing director, Skye Schillhammer, the company has no plans to produce a gravel bike at this time. "I can't say we won't ever make one, but at the moment we are sticking to the mountain category," he said.

And then there’s Yeti Cycles. The iconic race-focussed Colorado brand has yet to produce a gravel bike of its own, but many years ago it did do a small run of cyclocross bikes. Also, Yeti has arguably dabbled in the space via a colour-collaboration with Open Cycles dating back to 2018 (side note: Open’s original UP is one of the most influential bikes in gravel’s short history, but I digress).

Yeti Cycles' athlete, Geoff Kabush, is a common sight at many gravel events racing a Yeti-coloured Open.

Asked about whether Yeti Cycles may release a gravel bike at some point, the company’s director of marketing, Garrett Davis, said “There is no current development planned in the gravel category for Yeti Cycles. We are devoted to making mountain bikers faster and that remains our goal. This is evident in both the new bikes we’ve recently launched as well as with the Special Projects bikes we have designed for our best athletes.”

And then we get to the smaller-sized and arguably niche players (at least as far as bike quantities go) that have stuck to flat (and riser) bars. Guerrilla Gravity, Unno, We Are One, Hope, Privateer, and Pole are just a handful of more recognisable names on this list. How many will still be on this list in 12 months' time is a good question to ponder.

It goes in reverse

Of course, the whole movement of playing outside your regular game has certainly become a common theme for previously hardcore road brands, too. These brands are seeing a surprising number of their customers find off-road cycling through gravel, and these same customers are then looking to progress things further with a mountain bike.

From a marketing perspective, a number of these road brands have athletes competing in series such as the Life Time Grand Prix in the USA, or perhaps they're seeking a presence at the next Olympic mountain bike race.

Regardless of whether these road brands are offering mountain bikes to satisfy their athlete or customer needs (or both), there's little doubt that such an investment only adds further fuel to gravel bike sales.

In just the last two years, we’ve seen Cervelo and Factor enter the mountain bike space – only a few years after each brand entered the gravel segment. Meanwhile, the likes of Pinarallo, Ridley, and Wilier have increased their investment in mountain bikes (or simply returned to the space in the case of Pinarello).

There’s an even longer list of hardcore road brands that don't currently offer a mountain bike but wouldn’t dare miss the gravel boom. Iconic brands such as Colnago, Look, Time, and De Rosa all offer gravel bikes today, but there are no mountain bikes currently in their line-ups (although in many cases, there have been before).

The future of gravel?

Obviously, the gravel category is hot, and brands don’t want to miss out on their slice of the pie.

Two years ago Canyon Bicycles had suggested that e-bikes and gravel bikes were the two biggest and most exciting categories for the company. At a similar time, Cervelo had suggested that its still relatively fresh entrance into gravel had overtaken its triathlon bike sales (for which it’s a market leader).

So how big is the gravel market? And is there more growth to come?

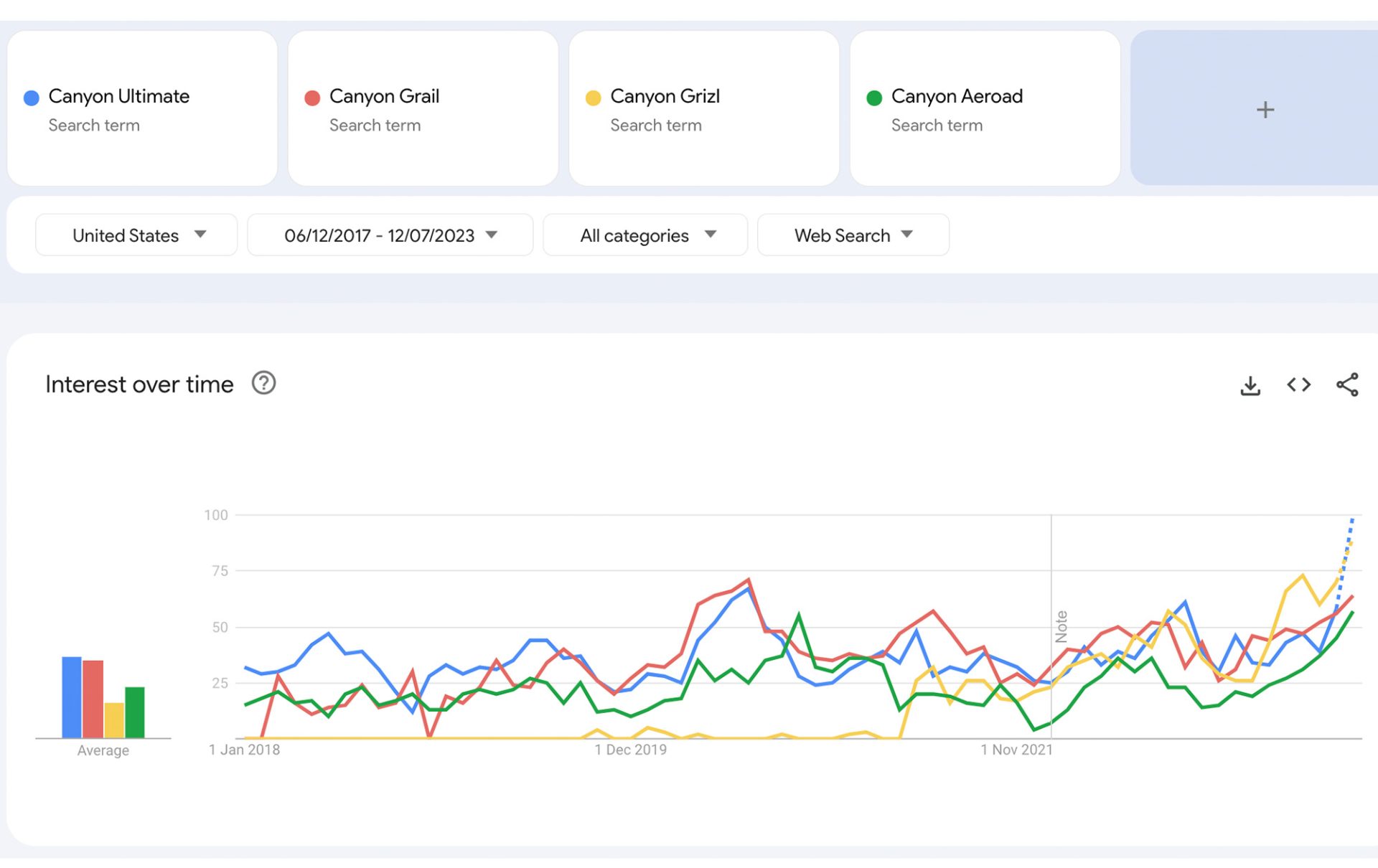

Playing around with Google Trends, a tool that provides some insight into comparative search demand, it's quite clear that the gravel segment is worth a fair bit to a number of popular bike brands. Search demand doesn't necessarily equate to sales but looking at brands such as Giant, Specialized, Canyon, Trek, Cannondale, Niner, Santa Cruz, and Cervelo does reveal that their respective gravel bikes are either in a similar ballpark to popular models from their road and mountain ranges, or at least that interest in their gravel bikes is trending upward. The trend is undeniable for searches within the USA, while global-based search results show a similar trend emerging.

According to a market study done by Reliable Research Reports, the gravel segment was worth US$491 million in 2020 and at the time, was projected to reach a value of US$858 million by 2030. The report projected a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.1%, which if true, is like cartoon dollar signs in the eyes of investors.

In recent weeks I posed the question of expected gravel market growth to a number of industry people, and in all instances, the answer suggested an expectation of continued growth. Unfortunately but understandably, none I spoke with were willing to share specific numbers.

“Continuing on the same path, and definitely getting bigger,” said Turner from Santa Cruz in response to my question of where they see the gravel market in 3-5 years from now. Even Yeti Cycles, a company with no intended investment in gravel, believes it’ll continue growing.

And then there are other indicators, such as SRAM’s recently revealed entry-level Apex dropbar group being solely focused on the needs of gravel riders, with little care given to budget-conscious roadies.

Personally, I agree that gravel has some real growth in it yet – especially outside of the USA (the USA was the birthplace and major growth market for gravel, but others are now following). I also see the early stages of a trend where road and mountain bike-specific brands each better play to their own strengths.

The road brands will likely continue to push faster, racier, lighter, and more integrated gravel bikes. Or put another way, gravel bikes that bring the feeling of a road bike to the off-road, and perhaps even serve as something of a do-it-all drop bar bike for those that want one bike to do road and gravel rides with.

At the same time, the mountain bike brands will likely pursue the rowdier gravel side with more versatility, better off-road capability, more integrated accessory storage, and perhaps open compatibility to run things like suspension forks, dropper posts, and in turn, keep with externally visible brake hoses. These are the brands that are likely to keep pushing the envelope of geometry.

Such examples of more mountain-bike-like gravel bikes are already seen with the YT Szepter, Canyon Grizl Trail, and Giant Revolt X. And then, we’ve seen glimpses of the next-generation Santa Cruz Stigmata that looks to have a suspension-corrected geometry and the versatility that brings.

And of course, the full-service brands (e.g. Giant, Specialized, Trek, Cannondale) will continue to offer a spectrum of gravel bikes. And with the budgets these biggest brands have, they'll likely continue to be the ones with some of the more daring designs – such as the somewhat silly Diverge STR we saw from Specialized recently.

Whether road brands will be able to entice some mountain bikers over with their sleek offerings, or if mountain bike brands will be able to acquire previously hardcore-road customers is something I’m sure every marketing manager with a bike brand is eagerly watching. Regardless, it seems there are plenty of new customers coming from multiple directions for brands to pursue. And for customers, more choice is rarely a bad thing.

Did we do a good job with this story?