Whereas it was only just a few years ago that seemingly every mountain biker just had to have a long-travel enduro-style machine, the pendulum has now swung in the other direction as short-travel bikes are definitely the hot segment of the moment. Case in point: Italian (née American) brand Lee Cougan has eight cross-country bikes in its catalog, but only one enduro model (two if you include the e-assist version). And following up on the attention garnered by its innovative Rampage Innova that debuted two years ago, Lee Cougan has released a more conventional 120/120 mm bike called the Crossfire Trail.

I say “more” conventional because it’s definitely not without a whole bunch of quirks. But do those hold it back or add into the fun factor? As it turns out, the answer to both of those questions seems to be “yes.”

Good stuff: Impressively light, flickable handling, great rear-end stiffness, good value, offbeat brand name.

Bad stuff: Offbeat brand name, so-so suspension performance, soft front end, goofy shock mount, curiously low grip height, overly XC-oriented build kit.

Lee who?

I’ll admit to not being very familiar with the Lee Cougan brand, and was genuinely surprised when I discovered that it wasn’t named after a person – well, not exactly, anyway.

“Mr. Lee Katz, a curious and enterprising man of solid Russian origin, was part of the group of enthusiasts that gravitated around the founding fathers of mountain biking,” reads an explainer on the Lee Cougan web site. “In 1977 in Evanston, Illinois, he decided to create his own brand through which to market his bikes. He chose the name Cougan because it is very similar to cougar, one of the symbolic animals of the North American wilderness.”

Wait, so Mr. Katz used his first name and then randomly modified “cougar” to “cougan”? Uh, ok. Regardless, the company was eventually relocated to Italy in the early 1990s under the Stardue corporate umbrella (together with road-focused brand Basso) and after apparently enjoying some success there, Lee Cougan is now trying to come back to its homeland.

One could almost argue that Lee Cougan’s Rampage Innova cross-country bike is better known than the brand itself, a wild full-suspension machine that used a carbon fiber leaf spring, a pair of micro-dampers, and a zero-pivot rear end to provide a scant 30 mm of travel on a frame supposedly weighing just 1,300 g – that’s within striking distance of endurance road bike category, folks.

The newer Crossfire Trail is far less radical than the Rampage Innova, offering a very normal 120 mm of travel front and rear through a wholly conventional flexstay rear end and matching Fox 34 Step-Cast fork, and mimicking Scott’s philosophy with the use of a dual three-position remote lockout for on-the-fly suspension control. Lee Cougan builds the Crossfire Trail with lots of carbon fiber – including for the front triangle, the rear end, and the shock linkage – and perhaps not surprisingly, the claimed weight for a medium frame is impressively low as a result at just 1,850 g including the rear shock – barely 50 g heavier than Specialized’s latest Epic Evo 8.

Lee Cougan isn’t billing the Crossfire Trail as some wispy lightweight, though, instead highlighting some more stiffness-focused claims.

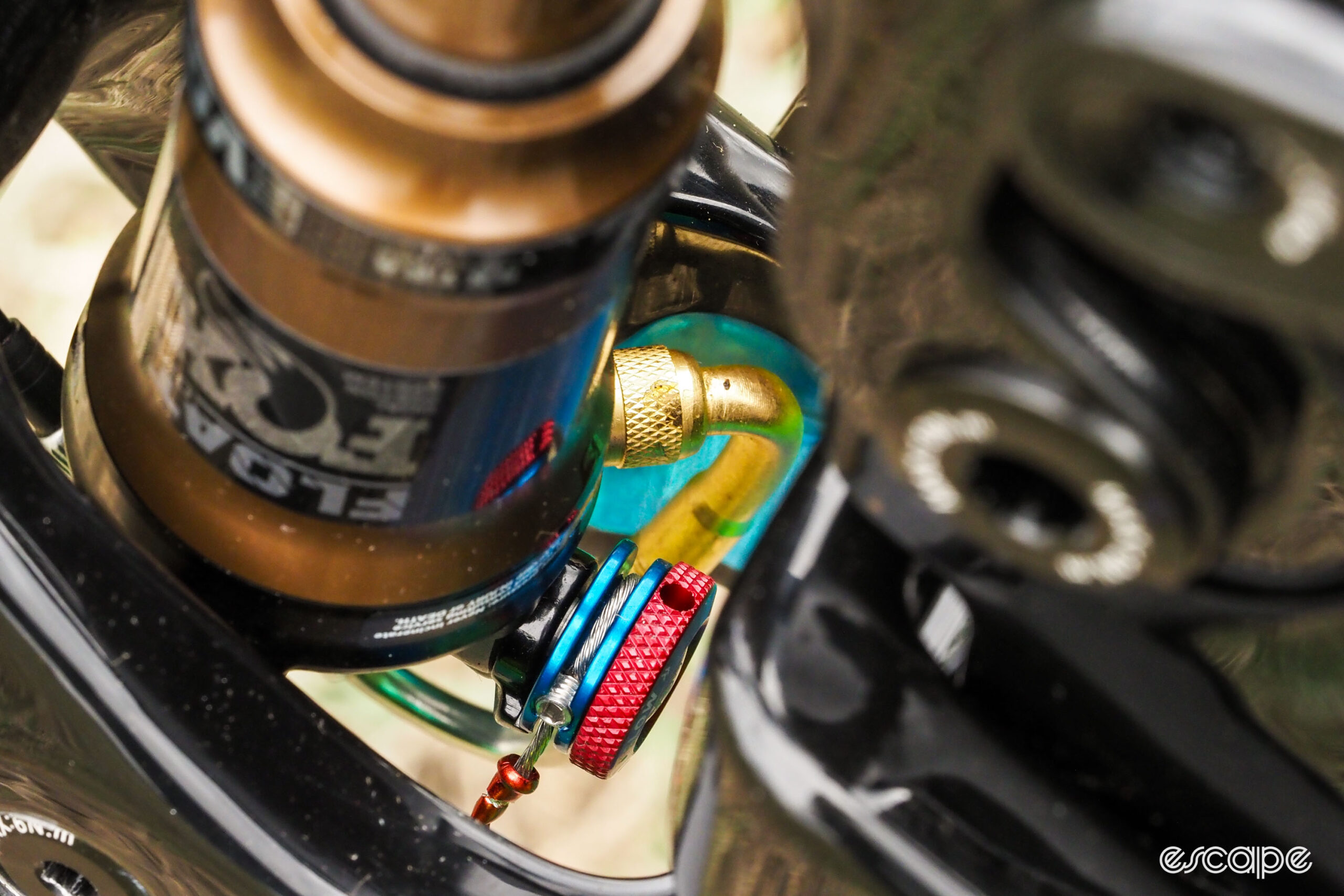

While many companies have moved away from vertically oriented rear shocks so as to make space inside the rear triangle for dual water bottles, the Crossfire Trail not only sticks with it, but supposedly uses it to its advantage. The inverted shock uses a popular trunnion-style mount at one end, but that end is situated so far down that the down tube has to be split in half to accommodate it. According to Lee Cougan, the shock mounting hardware then works as a sort of structural brace between the two halves.

Out back, the entire rear end is a single one-piece carbon fiber assembly, with a loop joining the chainstays in front of the seat tube. A more typical bridge arrangement would serve the same purpose to prevent independent movement between the two sides, but moving that connection to inside the front triangle allows for more tire and mud clearance. Oversized cartridge bearings are pressed directly into the seat tube, and everything rotates on one-piece thru-axle-style aluminum shafts.

Other features include headset cable routing (of course – sigh), a PF92 press-fit bottom bracket shell, a SRAM UDH-compatible rear dropout, and a secondary mount underneath the top tube for either a second bottle or bag (no need to attach a tool here, as the Crossfire Trail includes a Granite Designs multi-tool inside the steerer). Tire clearance is rated at 29x2.4” at either end.

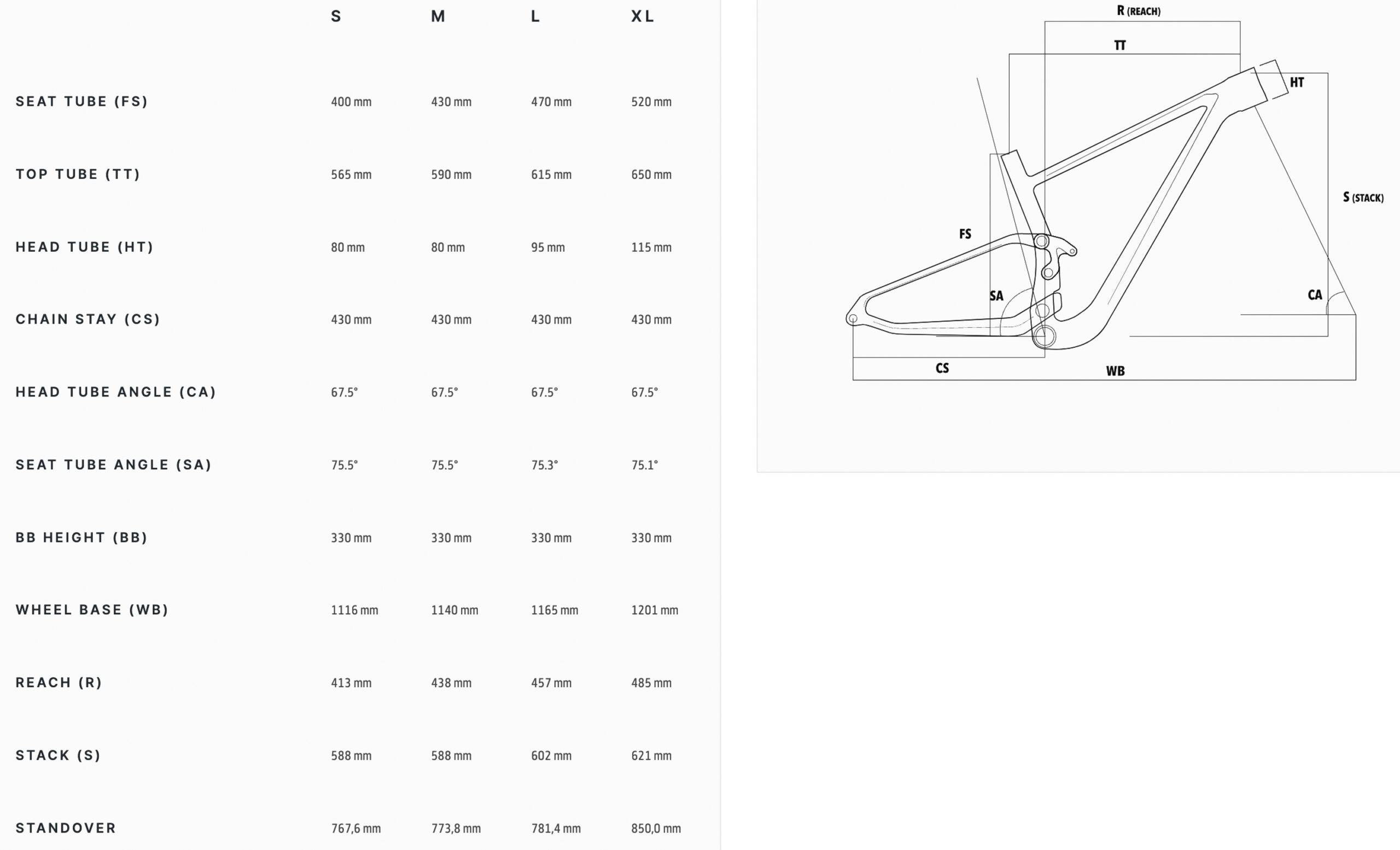

Frame geometry comes off as a bit old-school, although that’s not necessarily a negative depending on your preferences.

Head tube angle on each of the four sizes is on the steeper side at 67.5°, while the effective seat tube angles are only modestly upright at 75.1-75.5°. Reach dimensions are on the shorter side – just 438 mm on my medium-sized sample – but stack figures are unusually low for ultra-aggressive positions should you so choose. How low, exactly? On that same medium size, it’s just 588 mm – 15 mm lower than a Scott Spark RC.

The Crossfire Trail is offered in three models, starting at US$6,400 / AU$8,100 / £4,970 / €5,250 with SRAM GX Eagle Transmission and Microtech RK 25 aluminum wheels, and topping out at US$10,000 / AU$13,110 / £8,040 / €8,500 with SRAM XX SL Eagle Transmission and DT Swiss XRC 1501 carbon wheels.

Lee Cougan provided for me a loaner flagship build, which tipped the scales at just 10.88 kg (23.99 lb) for a medium size without pedals or accessories.

Ride report

The Crossfire Trail is likely be the most obscure mountain bike I’ve tested in recent memory, but it also proved to be one of the most interesting ones, too – although not necessarily for all the right reasons.

The low weight and quick-handling geometry made it a joy to toss about on the trail, deftly snaking through tight trees and playfully dodging embedded rocks. It’s darty and quick, almost like you’re inside the kind of MTB-themed video game that Zwift only wishes it could be. Flick the wheels around that exposed root or use it to boost up and over the whole section instead; the Crossfire Trail is perfectly content to do either.

That playful demeanor isn’t limited to the Crossfire Trail’s handling, either; it’s also fun to step on the gas and feel the bike accelerate. At times, it almost seemed like the bike was goading me into pushing on the pedals a little bit harder just because it could. The bike’s name suggests it’s more of an all-day machine, but on the trail, it seems like it’s all about the short-and-punchy stuff.

Nevertheless, its (very) slightly longer suspension travel relative to a pure XC machine also makes the Crossfire Trail a bit more capable on rougher terrain. Granted, 120 mm of travel could hardly be considered particularly generous, but as compared to properly short-travel thoroughbreds like the Trek Supercaliber or Specialized Epic World Cup, the rear end of the Crossfire Trail is a heck of a lot more forgiving if you left your finesse at home one day.

If you want to just stay seated and power through a section of moderate chunk, letting the suspension do much of the heavy lifting for you, have at it. It’s not especially supple on smaller stuff (and the medium digressive compression tune Lee Cougan selected for the Crossfire Trail helps explain why), nor is it exceptional in terms of traction on technical climbs, but once it’s into its travel a bit, it does a pretty decent job staying stuck to the ground.

As entertaining as the Crossfire Trail was in some respects, the overarching sense I got of the bike while testing was that it was confused about what it was. Is it a trail bike or an XC racer? And in that confusion, the bike unfortunately makes some big compromises.

It’s a good thing the bike has that dual three-position suspension remote because the Crossfire Trail needs it. Although it doesn’t seem to impact power transfer too much, there’s noticeable pedal-induced bob on smoother terrain if you’re not mindful to put the rear shock into at least its platform mode. The swingarm pivot is situated slightly below the top of the chainring, and chain forces work to compress the suspension with each power stroke as a result. It’s not horrible, but it’s also not as good as a modern full-suspension bike could – and perhaps should – be. In my head, it’s almost like the bike was potentially designed around a smaller chainring (which would situate the chain closer to – or even slightly below – the pivot axis), but was upsized to a 34T at the last minute for whatever reason.

Mind you, this characteristic of the suspension probably wasn’t by mistake. Scott Sparks have featured a similar philosophy for ages, after all, with the argument that rather than compromise downhill performance in the fully open setting to gain pedaling efficiency, instead you could always pick with a flick of your fingertips. That may be, but the problem is that the Crossfire Trail doesn’t come off as an unusually good descender in that open setting, and given the choice between a suspension design that doesn’t need me to constantly fiddle with it on the trail to be efficient and a more-sophisticated one that doesn’t need me to do anything, I know which one I prefer. Perhaps you feel differently.

Lee Cougan also makes a big deal about how the rear shock bolsters the stiffness of the down tube stiffness. The bottom bracket area does indeed feel very stiff in when it comes to combating pedaling-related flex, but I’m not sure I’m buying the reasoning. The down tube is huge – that’s where I’m guessing the stiffness comes from – and situating the shock in between the two sides like that mostly just seems to make it more difficult to make adjustments. The arrangement also leaves the shock more exposed to stuff flying off of the front tire than I’d like, and there isn’t even a cover to shield delicate bits from rocks.

Sticking to the frame stiffness theme for a bit, rear-end stiffness is excellent. The back half of the Crossfire Trail inspires confidence when really pushing the bike down through a turn, with little sense that it’s popping and twanging about if you hit something mid-corner. Just smash it through. The wide-and-flat seatstays occasionally rubbed on the inside of my calves, but if that’s the price to be paid here for that kind of resistance to flex, so be it.

It’s unfortunately a different story up front. While the bottom bracket area seems plenty rigid, the head tube is much more prone to out-of-plane flex. The steering geometry may be quick and nimble, but in certain situations, there’s a lack of precision that could sometimes trip things up as you waited for the front end to settle down a bit. Was this due to the somewhat narrow top tube? The carbon fiber blend? The lay-up schedule? I can’t say, but whatever the cause, the effect was sometimes disconcerting.

Build kit breakdown

Lee Cougan describes the Crossfire Trail as a “trail” bike, but the build kit practically screams “XC race” – and it’s both better and worse for it as a result.

Much of the straight-line and climbing speed of the Crossfire Trail can likely be traced to the 29x2.4” Maxxis Rekon Race tires mounted both front and rear. The low-profile tread is fast-rolling and offers decent grip in the dry, but that comes at the expense of braking and drive traction, and certainly cornering hold in anything other than ideal conditions. Maxxis admittedly has more XC-oriented treads in the corporate catalog, such as the ultra-minimal Aspen. However, even Maxxis classifies the Rekon Race as a cross-country tire, and moving up to a standard Rekon up front would offer a welcome boost to the Crossfire Trail’s capabilities.

Further bolstering the XC race theme are the 175 mm-long SRAM XX SL Transmission crankarms and 34-tooth chainring – 170s and a 32 would have been more fitting – as well as the two-pot Magura MT8 SL disc brakes, which are supremely light and offer superb modulation, but lack in ultimate bite at the limit, even with the 180 mm-diameter front rotor.

Nowhere is the XC race motif more overt, however, than in the Ursus Magnus HX.01 one-piece carbon fiber bar-and-stem combo. It’s light at 275 g (claimed) though not outrageously so, but the -12° stem angle combined with the Crossfire Trail’s super short head tube offers the potential for a ludicrously low grip height – like, we’re talking Nino Schurter levels of bar drop. Does this make sense for a “trail” bike?

It perhaps goes without saying these days that the one-piece bar-and-stem combo is also paired with headset cable routing. Ursus at least makes an attempt at mimicking a truly clean setup with the T-shaped channel cover that clamps the lines in place before they take a downward into the frame, but between the dual remote lockout, the dropper line, and two brake hoses, even the use of SRAM’s wireless XX SL Transmission drivetrain can’t deliver the tidy appearance that headset cable routing so often promises, but typically fails to deliver.

Perhaps I’m being too hard on Lee Cougan here for following a move that someone else started, but I still think it’s a ridiculous trend with no benefits – but lots of downsides – for regular riders, and someone needs to take a stand somewhere.

Speaking of XX SL Transmission, my opinion of SRAM’s latest wireless mountain bike drivetrain hasn’t changed. Upshifts and downshifts remain uncannily positive, even under full pedaling power; it’s truly incredible in the way you really can shift like a complete idiot and get away with it completely unscathed. However, the shifts themselves still happen a lot slower than I’d like and the shifter’s two-button ergonomics leave a lot to be desired. After months of playing with different orientations and mounts on other bikes, I eventually gave up on my own trail bike and went with an older-generation AXS rocker-style shifter instead. Granted, this is a personal preference issue, and one that thankfully isn’t terribly expensive to change if you deem it necessary.

Finding itself

Do I sound a bit conflicted about the Lee Cougan Crossfire Trail? If so, that’s because I am. On the one hand, its unusually low weight, nimble handling, and fast rolling speed make it more entertaining than most trail bikes. However, Lee Cougan has XCified the build kit (and perhaps the geometry) so much that you could easily argue the Crossfire Trail isn’t actually a trail bike at all, but it’s instead just a slightly longer-legged cross-country racer.

Is that a bad thing? I can’t decide if this makes the Crossfire Trail less capable than it should be, or if it’s just a matter of poorly chosen nomenclature.

Perhaps the bigger question is who this bike is for. Although the pricing offers impressively good value all things considered, there just isn’t much here to help the Crossfire Trail stand out amongst its more refined competition, particularly given the lesser-known label and what I’d anticipate to be much poorer resale value. Is the decent performance, quirky build, and offbeat brand name enough to pull people in?

Maybe, but my hunch is that, at least for the US market that Lee Cougan is trying to get back into, it’s going to be an uphill battle.

More information can be found at www.leecougan.com.

Did we do a good job with this story?