Who amongst us hasn’t dreamed of simply stopping it all and riding away?

Erik Binggeser eats donuts out of dumpsters and pizza out of boxes picked up on the roadside and hasn’t lived anywhere in particular for a very long time. He has a huge beard that fits his nomadic life; over 20,000 miles pedaled last year on a cargo bike that weighs anywhere from 150 to 200 pounds, depending on what he’s got inside it, from Arizona to Texas, Florida to Maine, and many points in between.

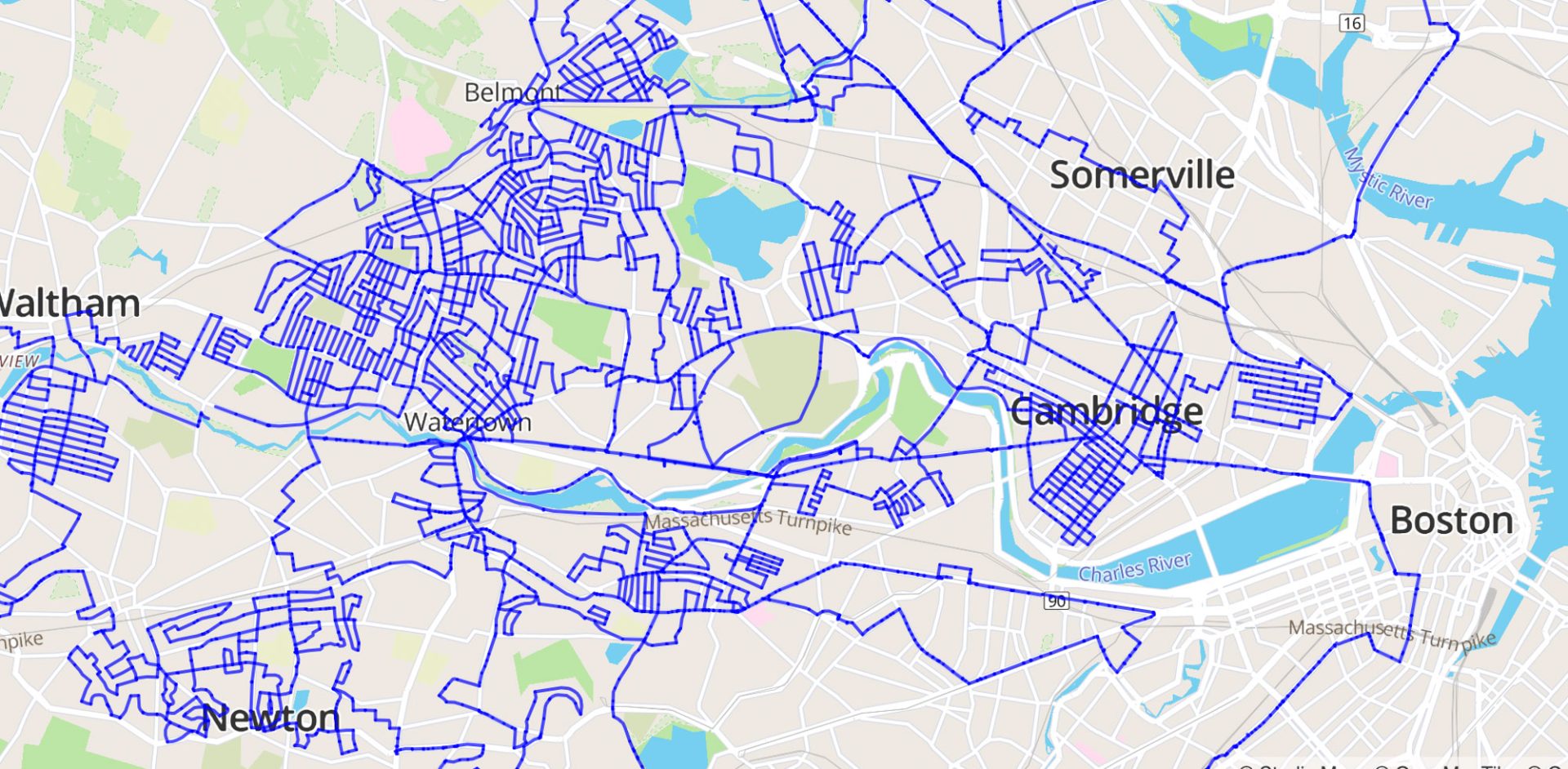

He left behind a day job. Graphic design, good pay, riding bikes with shaved legs in Austin, Texas. The pandemic broke him or maybe fixed him in some way, and he started filling in every available nearby street on his Wandrer map – a tool that syncs with Strava to gamify exploration, counting up how many new miles you’ve ridden. A few years later, Binggeser has an official title: Most new miles ridden in 2023. An incredible 18,113.7 of them.

That’s 29,158 kilometers of new roads – enough to cross the United States six times, all on that cargo bike. But he didn’t cross the United States six times. Many, if not most, of those miles came within relatively small areas, riding every inch of a city’s road network, picking up cans (well over 10,000 of them) and trash. Seeing things at a pace that makes it possible to really see them, he says.

Did he actually ride more unique miles than anybody else on Earth last year? Who knows. It doesn’t really matter. There are folks riding around the globe all the time who could probably put in a claim. But on Wandrer, at least, nobody saw more new bits of this planet than Binggeser.

The experience has radicalized him in ways many of us can relate to. He’s anti-car, but thoughtfully so. When you view the world as a pedestrian 100% of the time, you can’t help but begin to see cities and infrastructure and the very underpinnings of our society a bit differently.

Working on a theory that boring people rarely do unusual things, I caught up with Binggeser while he was hunkered down for a few days in Galveston, Texas, avoiding a cold snap and staying with a medical student he’d connected with via Warm Showers, a site dedicated to matching up people with a place to stay with people who need one. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Caley Fretz: How did you get here? What led to this?

Erik Binggeser: I grew up in Michigan, skateboarding, went to art school in Georgia, in Savannah, from there moved to Austin and lived and worked there for 10 years and that’s where I got into bikes. Started commuting and then group rides and all that sort of stuff and collecting, and at my worst, I had 23 complete bikes in my apartment and probably enough stuff to build 10 others. And you know COVID happened and things fell apart and I sold everything I owned and moved into my van for a year. And that was a good in-between step from big condo full of bikes and now living on a bicycle.

So I hopped around in the van for a little bit. I got the idea to do a cross-country cargo bike tour because I haven’t seen anyone do it on this kind of bicycle. So I ordered a bike from Omnium and ended up in Tucson, Arizona waiting for it to arrive. Bike arrived. Around this time I discovered Wandrer, just after seeing people’s Strava descriptions, right? I’m guessing that’s where most people see it. And being new in Tucson, I didn’t know anybody, didn’t know the city. I figured I would just start filling in the roads.

And riding around an empty cargo bike feels kind of silly. I mean, I know everyone does it. It’s like driving your F350 around with nothing in the bed. Right? But even more so on a cargo bike. So I just started picking up trash. And because I approached most things with like, if I can make some sort of game or challenge or rule for myself to motivate me to do a thing. I will do that. So then it became picking up every aluminum can that I found.

And then it was like, “Oh shit, how can I get the most like what are the most optimal route? How do you fill in a neighborhood without overlapping?” And I got so good at that in Tucson and I guess documenting it in the way that I was that a company in Tempe [Arizona] called Culdesac sponsored me to come up there and they gave me free rent for six months while I rode every road in Tempe and picked up every can I could find. [Culdesac is a master-planned, mixed-use development in Tempe that is billed as the first car-free neighborhood in the United States. – Ed.]

It was the goal was to get 10,000 cans in six months. And I easily did that, and filled in the whole city. And while I was doing it, Tempe has a really good 311 system for reporting problems with the city, like lights being out and sidewalks being broken and stuff like that. And as I was biking around, I was submitting reports for everything that I found.

A number of things have broken my brain over the last few years. But one of the big ones is that no city would ever pay somebody to do a full, top-to-bottom sweep of their whole city from a pedestrian point of view, right? Like, submit everything wrong. But I did that in Tempe just because I’m a maniac, and I like riding my bike.

I put in hundreds of reports for it. Every couple of weeks or a month or so I still get the email confirmation of them completing something that I submitted, like a crack in a sidewalk that’s too big for a wheelchair to get to, like all that sort of stuff.

Picking up the cans and filling in the roads and all of those sorts of things, it really changes how you look at a place. Bikes are the great equalizer in so many ways. And when you explore a place, whether on a bike or foot or basically outside of a car, you get to see it and experience it and smell it and taste it and interact with people.

In Phoenix, you feel the disparity between the rich neighborhoods with grass lawns and tree coverage, all these things that exist because they can pay for water, where the ambient temperature is like 10 to 15 degrees cooler than the neighborhood south of the airport where it’s just dirt, no tree coverage. You can’t experience that in a car, right? And people have to live in those places because they can’t afford to pay for water. [It was] another thing that broke my brain.

Caley: Need to take a quick step back. Why did a company pay you to come pick up cans in Tempe?

Erik: They’re doing an artist-in-residency program. The cliché example of that is if you’re a person who paints murals, come live in our complex, our building, and you paint a mural on the side of it inspired by living there. Culdesac is building the first car-free community. Basically, what if you made an apartment complex where there’s zero parking, like literally zero parking, what would you put in the parking places in the parking lot? You can put more units in, more people in the same space, you can put more tree coverage, more community spaces, and more common areas again to connect with your neighbors and get to know the people around you.

I think in my original pitch I was going to try and make some kind of art out of the cans, like a sculpture or melt them down or something, which never ended up happening because I have no idea how to cast aluminum or anything like that. But I did end up taking the cans to a scrap yard getting them turned into money and then donated the money to Bicycle Saviors, which is like a local bike co-op, so it has somewhat of a cyclical nature like trash to helping the community.

But my time with them ended on November 20, 2022. And that’s when I dropped my keys off and headed out from camping on the cargo bike. And I’ve been riding it around the country since and always looking for new roads.

Every trip is an excuse to cash in on every friend, anyone who’s ever been like, “Yo, if you’re ever in Philly, you can crash on my place.” I’m like, “Alright, I will drop a pin. I will call you when I’m a week out.”

I’ve got stuck in Gainesville for three weeks, I got stuck in Tampa for a month, and my first time around Miami for three weeks. Philly for 10 days, Boston for a little bit. I’ve never been the typical tourist, like, go to the restaurant, go to the museum type of person, I want to see the streets of the city. And I wanted to see how the houses are different, how the neighborhoods are different, how the infrastructure is different in different places. I feel like you get a sense of it better than whatever the city is trying to present.

I went back through Austin, Texas, on my way east. And having lived there for a decade, riding bikes, eight to ten thousand miles a year. With the Wandrer thing, I’ve only ridden 23% of the city. And so when I came back through, I was like, “Okay, I’m getting as many new roads as I can. I’m gonna see as many new parts of the city as I can.” And I commuted from north to south down all the streets. Maybe 1,000 times I’ve ridden this road and never ridden like one street or two streets to the side of it. Why would you, once you know the safest, quickest, smoothest, most comfortable way to bike from your house to work the bar to the grocery store? Why would you do anything other than that, right? Unless you’re playing this very silly game?

Caley: Bit of a personal question. How do you make this work, financially? You still have to buy food.

Erik: I’ve gotten very good at dumpster diving. Literally 99% of my calories I don’t pay for, just because it’s just for diving. The finances though I, you know, worked. The stupid grind culture, like I had a degree in graphic design. I worked as a designer for the decade that I was in Austin, a bunch of freelancing, a couple of full-time corporate gigs, and some agency stuff, like making good money, doing 50- or 60-hour weeks at the office and spending all my money on stuff. Like I never traveled, I rarely ate out, and didn’t party. None of that. I spent all my money on like, camera gear and computers and like stuff. And then I sold all that stuff.

And so I have enough in savings right now, if I continue living this sort of frugal life, dumpster diving, as well as accepting the hospitality of people like the Warm Showers place that I’m in for four days now. You know, a little bit of bandit camping here, maybe a motel a couple times a month when I want to recharge like, I have enough money in the bank to do this for at least five years, maybe 10. And because I’m a designer, I can work on a laptop, anywhere that I have cell service. So if I need to go back to work I could.

It feels really good to be able to be picky about the gigs I accept, because before it was just hustle as much as you can because you that’s what you do. You know, take every gig, always overstretch yourself, no matter what the client is, no matter what they’re trying to sell. This year’s updated version of last year’s plastic whatever. But now, I get to be picky and only help, like, bike friends with their bike thing, or environmental organizations for photo projects for Adventure Cycling or bikepacking or things like that. Yeah, that’s cool. It makes me a much happier person.

Caley: Before we go any further, describe your bike for me.

Erik: Well, it’s about eight feet long. Fully loaded, it’s about 200 pounds, plus or minus depending on how many dumpster pieces I have on board. It’s a Dutch bakfiets-style bike.

I got interested in this style of bike from just following bike messengers on Instagram and people riding Omniums and the other varieties around cities with you know, 10 banker boxes up front, [or] a couch. I thought they look so god damn cool.

It has a 30-tooth front chainring and a 10-52 in the back. Running Gevenale shifters, friction. Twelve-speed friction is kind of insane. But it works because I can fix it anywhere with my eyes closed and like two hex keys.

It has mechanical disc brakes, TRP Spyres, just because they’re easy to work on. The bike doesn’t emergency stop. So I got to be a little careful when I’m bombing around a city. It’s annoying that it has a 20-inch wheel up front and 700c and back so I gotta carry it two different-sized tubes. It’s set up with drop bars with aero extensions. I have like 10 different hand positions on them to keep it comfy. It rides like a freight train. It is heavy. It is slow. It is the least-aerodynamic thing that I can imagine. But the joy that I get from every kid yelling, “Mom, look!”

It’s bad because it is bad for touring. Yeah, you people should not get a cargo bike for touring. You can’t put it in inside places. You can’t carry it upstairs. But it is the best thing for getting every good old boy to talk to me outside of every gas station I ever stopped at. And that gives me these little tastes of local culture and gives them a little learning moment of like maybe you don’t need your big lifted truck just to do groceries.

I’ve broken a lot of stuff. I’ve been through a bunch of cranks and now it has EE Wings on it, which is a little over the top but I was sick of breaking cranks. I go through tires every 7000 miles or so. It has a bunch of custom bags and I’ve sewn them together and modified them, there’s nothing on it that I haven’t mucked about with in some way, customized or decorated. My style goals for it is like a Star Wars junk trader speeder bike type of thing, with a bunch of crap hanging off of it. I kind of look like a merchant, like “Sell me your bugs for rubies.” Everyone I see is like, “That’s a heck of a rig you got there?” You bet.

Caley: Ride Finds is a thing. It even has its own Instagram account. Describe what it is for those unaware.

Erik: Oh my god. I used to be a roadie, right? Shaved legs, let’s go out and do a five-hour century with the boys type of thing. And at that pace, you are always aware of your distance, your paceline. You don’t have time to let your eyes wander and look around. But when you’re on tour going a little slower, you get to look at all the junk that’s in the ditch. And whether it’s bungee straps, microfiber cloth, hi-vis vests, multi-tool cases. A lot of food. I mean, obviously a lot of litter, right, but like, I found cans of food, I found half a birthday cake.

On the @Ride_Finds account, one of the recurring memes is people finding dildos on the side of the road. It is like a bike-touring bingo card. It’s one of the achievements when you find a dildo on the side of the road. Someone didn’t want it, they chucked it out their car window.

The vest that I wear, I found on the side of the road. The big flag sticking off the side of my bike I made from a horse whip that I found in New Mexico and a construction flag I found in Canada. Half the bags on my bike are from backpacks or laptop bags that I saw on the side of the road and like cut off and hand-sewed together. The road provides.

Oh, damn, I need a new buckle for this thing because I broke it or I need another two feet of webbing – you will find it on the side of the road.

Yesterday, I don’t know if you saw it on my [Instagram] story. I was riding around Galveston, just cruising the streets because the weather was nice and I wanted to get some more miles and I have this habit of checking suitcases that I find. People throw away suitcases. I check them because there are pockets and I will cut off the pocket and use it on one of my bags, or grab some webbing or a buckle. And there was this suitcase and I nudged it and it was heavy. So I unzip on the pocket. And they were two clips, or a magazine, of what turned out to be like armor-piercing rounds. Like just under 20 bullets. I posted on Instagram and apparently, a lot of my followers know a lot more about guns than I do because they were kind of losing their shit. I got a lot of I got a lot of like “whoa, America.” And then a lot of I’d like “America, hell yes.”

It’s Texas. It’s apparently not illegal to just throw away bullets. But it seemed a little gutsy, like $80 a bullet or something in this pocket. And I’m really glad I had gloves on when I touched them because you don’t want to be leaving evidence.

I’m not in a hurry. I can take the time to slow down and see what’s going on with the suitcase. Or let’s see what’s going on with this Igloo cooler, or this random cardboard box on the side of the road might have something in it. It’s usually nothing, right? Nine times out of 10 while dumpster diving or ride climbing or whatever, it’s nothing, it’s worthless. It’s trash. But then you get like, perfect pizzas from a Domino’s. Or like yesterday, I got some amazing donuts, and Colossus from a Shipley dumpster which will fuel me for the next three days. It’s such a fun game. You never know what you’re gonna get; usually nothing but sometimes, sometimes it’s something.

Caley: I have to imagine that’s a recurring theme for you. You must have had some weird days?

Erik: There’s a definitive answer for this.

When I’m riding, I do a lot of stealth camping behind churches. Because you would hope that a house of worship would be welcoming to people traveling and I always leave no trace. If there’s a pastor nearby, I’ll knock on the door and ask or whatever. So I’m somewhere in Virginia. And I had this church bookmarked and it’s not near any houses, middle of nowhere, perfect spot, like big wooded field behind it. And roll up and I’m out of water. The taps on the church weren’t turned on. Like they didn’t have water coming out, the water source was turned off. And I’m like, “Okay, I can make it, I’m not going to die, I’ll make it through the night. I’ll find water tomorrow, but it’ll be shitty. I’ll be in a bad mood, dehydrated.” So I get on my phone and I’m looking for a campsite nearby. And this one pops up and it’s five miles away. And it’s called Zebulon Grotto and it’s this glamping sort of place. And I give him a call. And I’m like “Hey, you know you have like fancy tents for like 200 bucks a night but I’m on this bike traveler, can I pitch my own tent?” And they’re like, ‘yeah, totally. No problem. But just so you know we’re a clothing-optional resort. That won’t be a problem?” That will not be a problem.

I ended up going there and end up hanging out and partaking in their vibes, I took a rest day the next day and just hung out by the pool buck-ass naked editing photos and chillin’ all day, all because the tap on the church that I planned to camp at didn’t have water.

That is probably the most interesting instance of something going wrong leading to something phenomenal happening. Going from disaster, no water, and then I get to hang out with the most accepting amazing people that I’ve ever met on the whole trip for a day. Being naked in perfect weather.

So far, every time something bad happens, it’s led to something amazing. And whether it’s showing up at a nudist camp or riding bikes with 1,000 people or making new friends, who knows what will continue to happen. And I think is the reason why I don’t ever want to stop doing this type of life, it’s just random and too fun and too many good stories.

Caley: What do you think about cars after all this?

Erik: I mean, it is the most brain-breaking thing, once you realize that we have constructed our entire world around this technology that has only existed for 100 years. Hopefully, it will not continue to exist for hundreds of more years, because it’s destroyed cities, it has destroyed so many lives.

When you look at the stats, like the straight numbers like 40-something thousand people in the States die every year interacting with automobiles. A million dogs die every year because they’re hit by cars. A million vertebrate animals die every day. That’s another thing you see when bike touring is a lot of roadkill. The costs that go into maintaining roads, building parking lots and parking minimums, and all these things,

It’s tough to try and fight against it and enact policy change. But thankfully, there are people who are doing great work to actually make change, like the War On Cars podcast, Strong Towns is a great organization.

If you only have to go a mile and a half, why are you driving? The most common feedback is “I’d love to bike. I’d love to bike my kids to school, but there are too many cars. I have to drive.” Alright, well, if all it takes is seeing five people biking to school, will you do it and then maybe there’s another person that needs to see six people biking to school, and then they’ll do it. And a group of people that if they see 10 people biking to school, then all of them will start doing it.

The term critical mass is wonderful because you feel it when you’re riding with that many people, like in the monthly meetups in cities, because you feel safe being around that many people who are also on bikes. Everyone on a bike wants everyone else to be on a bike. Everyone in a car wants everyone else in the car to stay home. The last thing they want is more people in cars on the road. And yes, they yell at me all the time.

Caley: I don’t know anything about your personal beliefs, but has this changed your view on fate and the universe and such?

Erik: The truth is that it definitely restored some of my faith in humanity. I think working in advertising, it grinds you down. Working in any big corporate job, you probably get ground down and get kind of misanthropic about things like climate change and the world ending and politics and blah, blah, blah. The inherent like, “Wow, I get to ride a bike through here, and everyone’s gonna be shitty to me, but turns out like, people will buy me a sandwich or chat with me about whatever or offer me often the place to stay pretty much anywhere in the country, no matter what their beliefs are, or what their history is or where they’re from.” People are kind of good people. Despite all the attempted murder from people in big trucks trying to pass too close, like, there’s enough good people out there that have crossed paths with that you know, it’s not making me more of a spiritual person or anything like that. But making you more, I don’t know, have a little more confidence in people being good people. That’s how I think of it.

Did we do a good job with this story?