The higher you climb, the harder you fall.

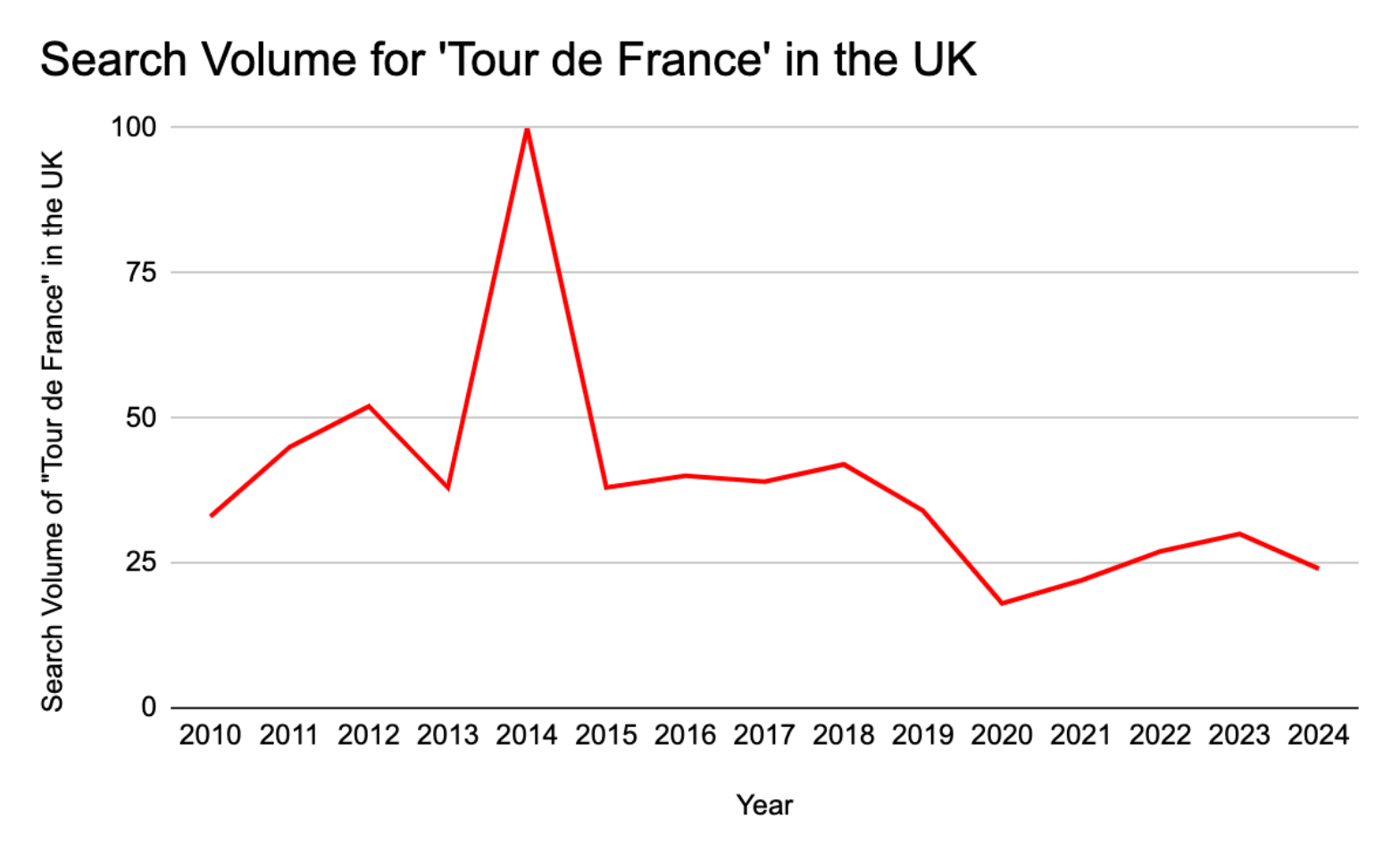

From its incarnation as Team Sky in 2010, the team swiftly rose in the sport's ranks, winning seven Tours de France in eight years. But after billionaire Jim Ratcliffe purchased the team and rebranded it as the Ineos Grenadiers, its position atop the sport has eroded – slowly at first but with increasing speed. In just a few years, cycling's once-dominant stage racing team has transformed from an innovative powerhouse into a rudderless corporation, haemorrhaging talent and results despite its massive budget.

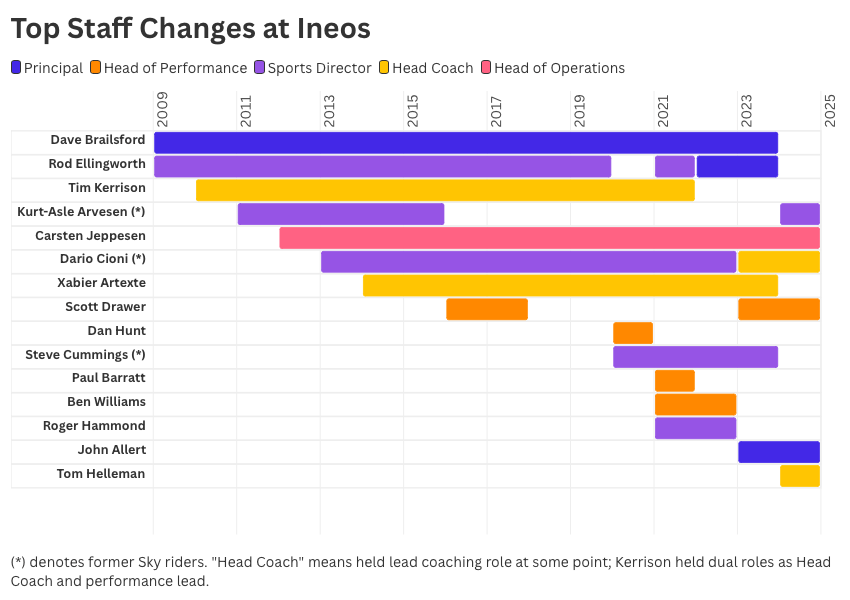

From the 2020 season on, the team has cycled through four different heads of performance, and as many lead sports directors, the most recent batch of which was announced just a few weeks ago. And while the team still reliably scores UCI points, wins – particularly in the Grand Tours that have always been the team's strength – have become increasingly scarce.

To dissect this empire’s collapse, Escape Collective spoke with more than a dozen sources in and around Ineos – former riders and staff, agents, and other well-connected people in pro cycling – to learn what took the team from winning at least one Grand Tour in 10 of 11 seasons through 2021 to struggling to hold onto talent both on and off the bike.

The dividing line between the team's old, Grand Tours-conquering era and its new, scrappier self is difficult to pinpoint.

Perhaps it was the upheaval of the pandemic-scrambled 2020 season or its 2021 sequel, which saw the emergence of Tadej Pogačar and Jonas Vingegaard and the rising juggernauts of their respective UAE Team Emirates and Jumbo-Visma squads to overthrow Ineos' previously untroubled hegemony.

Or maybe it was Egan Bernal's 2021 Giro d'Italia win, Ineos' last Grand Tour victory and one that came in a much different style to the controlling, mountain-train style victories of its 2010s heyday. Another good place to start is Bernal's life-threatening crash that next offseason.

But you can make an argument that Ineos' current era truly began later, with its 2022 plan to branch out and take their Grand Tour dominance to the cobbled Classics. Spring had always played second fiddle to the team's yellow jersey obsession. But with Bernal facing a long recovery and Ineos suddenly bereft of a single Grand Tour leader, Paris-Roubaix offered what looked to be a watershed moment.

Team founder and mastermind Dave Brailsford, not as omnipresent at races as he once was due to various health problems, stood defiantly and victoriously just past the finish line in the velodrome, hands aloft, to welcome his rider Dylan van Baarle home, just a week after the Grand Tour superdomestique Michal Kwiatkowski won Amstel Gold Race.

Standing trackside that day, there was the sense that spring had sprung for a team that risked being left behind.

After three years of turmoil and setback – the ownership change in 2019; the crash-induced decline of Chris Froome; the health issues of its charismatic chef de mission; the shocking death of beloved lead sports director Nicolas Portal, the keystone and heart of the team; the fallout from the Richard Freeman scandal that saw its former team doctor lose his medical licence and get a four-year anti-doping ban for ordering illegal substances "knowing or believing" they were for Sky or British Cycling riders; the eruption of the Pogačar/Vingegaard era; and the serious injury to Bernal – Ineos looked to have righted the ship and be weathering everything that was being thrown at them.

But since that day in the Roubaix velodrome, the results sheet speaks for itself. Zero Grand Tour victories, zero Monuments, and of the week-long stage races, only victories at the Tour de Suisse and Tour de Romandie when previously the likes of Paris-Nice and the Critérium du Dauphiné used to be won as warmups for the Tour.

If 2023 was shaky, it at least saw 38 wins including two stages of the Tour de France. But then 2024 hit, and the victory total dropped to 14 – the lowest in its history. Tom Pidcock, the team’s highest-paid and highest-profile rider, was openly agitated about his role and not-so-openly agitating for an exit, a move which looked close in October but ultimately fell through.

Staff turnover continues, with lead sports director Steve Cummings and highly regarded performance engineer Dan Bigham out the door, the latter publicly lamenting the lack of focus on his area of expertise. Criticism bubbled up publicly from the team's longest-tenured riders, Geraint Thomas and Luke Rowe. Even quiet, homegrown talents like Ethan Hayter described a “tricky year” with a team that “could do with a couple changes” as he exited the squad.

Hayter's mild critique undersells the state of Ineos. The team today is a shadow of its former self. “All of the smart people have left,” a former staff member told Escape Collective when asked to reflect on what has changed within the team.

“Things were alright with Sky,” one former rider added, “but with Ineos there is too much structure, compliance, and acting like a big corporation.”

The team’s go-getting, question-everything approach to all aspects of bike racing, from sports science to tactics, has been replaced by a cautious, corporatist ethos and calcified decision-making. That culture, and its erratic approach to top talent, has led to an exodus of top riders and key staff and alienated some still on the team, like Pidcock.

Ineos is still richly funded but scattered and ineffective, its billionaire owner Jim Ratcliffe dissatisfied at both its underperformance and being eclipsed by the sport's newest wave of top teams, as well as distracted by his newer ventures, chiefly his new controlling stake in Manchester United. Any path back to the team's former place atop the sport is unclear at best. And with Brailsford now focused on Ineos' football portfolio and unlikely to return to managing the cycling team, it's equally unclear who might lead that restoration.

When approached for comment or input on this story, Ineos Grenadiers initially turned down our request to speak to senior management on the various topics brought up by former and current employees. The team then did not respond to subsequent requests for comment, including to a detailed list of questions.

Many of the people we spoke to did so on condition of anonymity due to legal and professional concerns, but the picture that emerges is clear: a tale of internal politics, power vacuums, mismanagement and ego, of a sporting force reduced to a billionaire’s lethargic plaything. This is the story of Skyfall.

The Empire Fades (2022-2023)

After the seismic events of Portal’s death and increased suspicion sowed by the Freeman scandal, we can also trace a few key changes in backroom staff during the 2021-2022 winter period that sowed the seeds for the team’s precipitous fall in 2024.

The return of long-time coach Rod Ellingworth the year prior was fully explained when Brailsford was sucked higher up into the Ineos machine to oversee Ratcliffe’s sprawling, and underperforming, empire: the Mercedes AMG Formula 1 team, Britannia sailing, French football club OGC Nice, the All Blacks rugby squad, as well as the Ineos Grenadiers cycling outfit, of course. However, Brailsford still officially remained as team principal, with Ellingworth given the title of deputy.

While many people we spoke to point to the absence of Brailsford as being a reason for the downturn, one former staffer points out the decline began when the team’s founder was still at the helm; in fact, he still is.

“There's this huge thing about Dave stepping away from the team and things going to shit,” one source said. “But that trajectory had already started and he hasn't actually stepped away at all.”

In that 2021-2022 offseason, another key figure, Tim Kerrison, the mastermind coach behind the team's most successful era, also left after 12 seasons.

On the road, results continued to trickle in. Pidcock and Carlos Rodriguez shone to the extent that both secured lucrative new deals as other suitors circled. Pidcock’s new contract came after just one year with the team and was signed in the weeks after Bernal’s crash in 2022. The five-year deal, numerous sources confirmed, is in the €3-5 million range, making him the highest-paid rider in the team, and within the top five or even three biggest earners in the entire peloton. This bumper contract would have required sign-off from Brailsford.

Even before Rodriguez signed his own four-year extension in October 2023, there were tensions with Pidcock, and the team proved inept at managing a precocious and sometimes petulant talent in whom they’d invested significantly. A scene from season 2 of Netflix's Unchained filmed at the 2023 Tour de France thrust those strains into the open.

In the scene, Pidcock and Cummings, then an assistant sports director, talk about what the team's strategy should be for the coming mountain stage. “The logical thing is that I ride for Carlos. But I’m not riding on a flat bit, killing myself, and getting dropped,” Pidcock answers matter-of-factly when Cummings asks what Pidcock thinks he should do given that Rodriguez is a minute ahead of him on GC with only a week left to race.

Cummings then tests the waters. “I think we have to commit to Carlos. Do you agree?”

“I’m not sure … to be honest,” answers Pidcock.

“What are you not sure about?” inquires Cummings.

“Can you turn the cameras off, please?” Pidcock requests, not wanting whatever was said next to make it into the public realm.

Normally, it would have fallen to Ellingworth to handle the riders' roles and hierarchy; as he noted in the same Unchained episode, “managing [riders’] egos and personalities is part of the job." And Ellingworth has particular experience and skill in that role, having been a steady hand behind similarly precocious British talents such as Mark Cavendish. In many ways, Ellingworth represented a continuation of Brailsford's leadership. But Ellingworth neither had full decision-making power – due to Brailsford’s position above him in the org chart – nor was he a leader of the same inspirational ilk.

A key component of Brailsford's success, a recent employee explained, was his charisma and attention to creating a solid culture, while also being able to come up with clever ideas and knowing how to put together a plan and execute it with the right people in place. That staffer viewed Ellingworth as less of a visionary, lacking Brailsford's level of understanding of the sport from a performance perspective. In the staffer's words, Ellingworth was "trying to be Dave because Dave wasn't there. He really just tried to do similar things but failed pretty miserably."

Sports science was a particular area of concern. Brailsford admitted in late 2020 that his team had “continued to work with their heads down, but didn’t notice other teams were overtaking them." Yet sources tell of instances as late as 2022 when it felt normal to hear staff say, “This is how we did things in 2014," or, "We did this during the Sky era." That thread apparently ran all the way up to management, as Ellingworth didn't look to break from the past.

“Predominantly, Rod set the tone and he was taking leave from what Dave had always historically done,” the staffer said. Ironically, working under these preconceived notions of what Brailsford would do set a stark departure from the question-everything, marginal-gain-focused approach that had helped birth the original success of the Sky era. In elite sport, if you’re not moving forward, you’re moving backward.

There is another reading of the situation. Two former employees told Escape that they believe Ellingworth was set up to fail. Brailsford had been promoted to run all of Ineos' varied sporting ventures, but he remained as team principal. Ellingworth was tasked with the day-to-day running of the team, but required a sign-off from Brailsford for most major decisions, according to one of those employees. Even minor issues got bottlenecked, they said, noting an instance at the 2023 Tour de France where getting a team vehicle sent in to replace a broken one was a decision that had to be passed up the chain. One person told us that in some cases, Ellingworth agreed to rider contracts before Brailsford then blocked the deals at the last minute, leaving Ellingworth with the fun task of having to tell those riders the bad news.

Ellingworth grew increasingly irate with the complicated structures at Ineos. “He was totally frustrated and burned out by the decision-making process," a well-connected former colleague of Ellingworth said. "Things were supposedly in his hands but they never were in reality, and he couldn’t get decisions out of people like Dave Brailsford.”

“[Ellingworth] couldn’t get through to Dave and in the end, enough was enough and he left because he couldn’t get decisions ratified,” another source who’s known both men for years added. “The problem is there are too many layers of management for decisions to be taken quick[ly] enough. He decided he needed to get out because he stopped enjoying it, and they were also starting to put the blame on him for things that weren’t his doing.”

In November, after the 2023 season had finished with a modest haul of victories – including two more Tour de France stages – Ellingworth resigned from the team for a second time, news called "gutting and sad" by team stalwart Geraint Thomas.

At first, Ellingworth refused to be drawn on his departure. After taking a role at British Cycling in March to become the race director of the men’s and women’s Tour of Britain (he would later announce a return to Bahrain Victorious, the WorldTour team he originally left Ineos in 2019 to join), he told journalists he resigned because “I just decided that it was time for me to finish. There were things that I wasn’t totally in agreement with and then I felt like life was catching up with me a little bit.”

According to multiple sources, it's common practice for employees to sign a non-disclosure agreement when they leave the team; past his brief statement, Ellingworth hasn’t publicly expanded on his exit. He did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

Certainly by the time of Ellingworth's departure, if not before, there was widespread bafflement and even anger at the way in which Brailsford had distanced himself from the team as he sought out new adventures in football and failed to bring in, in the words of one former staffer we spoke to, “someone competent enough to be his successor. What they’re left with is a huge leadership vacuum and it’s amazing how things have got so bad so quickly.”

The aforementioned former colleague of Ellingworth corroborated: “The basic problem has been that Dave lost interest, time, and commitment three years ago and that inhibited recruitment, budget issues, and decision making, and it’s why they’ve lost some key riders who they should have kept.”

A look at some of the riders, both experienced and young upstarts, who have left since 2022 and the teams to which they've gone paints this picture vividly: Adam Yates, Pavel Sivakov and Jhonatan Narváez (UAE), Richard Carapaz (EF), Dylan van Baarle and Ben Tullet (Visma-Lease a Bike), Tao Geoghegan Hart (Lidl-Trek), Dani Martinez (Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe), and Ethan Hayter (Soudal-Quick Step).

“When you look at the guys who’ve gone out and the guys who’ve come in, there is a big difference, that is no surprise,” said Geraint Thomas, who has been with the team since its first season, in an episode of his Watts Occurring podcast aired in September 2024. “That base in the team is a lot more fragile than what it used to be.”

The Great Unravelling - January 2024 to present

At last addressing the leadership confusion, Brailsford formally stepped down as Ineos Grenadiers team principal in January 2024 to focus more heavily on Manchester United Football Club. In both financial heft and struggles, Ratcliffe's latest sporting acquisition dwarfed those of the cycling team. Maybe Brailsford was half hoping for another stint living in a campervan in the car park of a football stadium, as he did with Ratcliffe's OGC Nice in October 2022, to fully dial in on turning around that club's fortunes.

A replacement for the cycling team was found in the shape of new CEO John Allert, who, after spending two years as the team's managing director – largely focussed on the business side of the organisation – would now oversee every aspect of the day-to-day running of the team.

Similarly, former Sky rider turned sports director Steve Cummings was promoted to head of racing, while Scott Drawer was hired back to the team as performance director, away from his position as director of sport at elite British private school Millfield.

The "new Ineos" was often all about trying to replicate the old Ineos, which meant a lot of culture meetings. At one of these meetings in early 2024, according to an employee who was present, Allert told the Ineos Grenadiers he wanted them to think of themselves as a "tribe," where everyone's job was to protect the tribe and if you didn't you'd be kicked out.

During this meeting, said the source, Pidcock raised his hand and said something along the lines of: "So you're saying if we don't fall in line we get booted out?" to which Allert replied: "Yes."

"Well, that's shit," was Pidcock's reaction, the employee recalled.

Another source with deep knowledge of the team corroborated the events, but said that Allert's presentation was instead a 40-minute monologue where he told the team it had not been performing to standards. Pidcock, the source said, was the only one to stand up and back the riders and staff from what he viewed as unfair criticism, which drew respect from a lot of the team.

This interaction set the stage for a relationship that made headlines throughout the season, as Pidcock tested Allert’s proclamation and, in general, got his way. Cycling is, fundamentally, an individual sport competed in by teams; that tension underlies much of what Ineos went through this year.

As the previously mentioned long-time associate of the team told Escape, “Ineos have set up an athlete-centred and -driven system which gives all power to [riders]. So when they tell Tom he has to go to this training camp or complete the Tour, he turns around and says no, he wants to concentrate on winning gold at Paris so will do it the way he wants. They don’t have control over Tom."

The lack of control over their 25-year-old star extended to Pidcock's absence from their pre-Tour training camp on Tenerife, with the Brit instead opting to stay in Andorra to prepare for the Grand Tour alone, where he could also focus on quietly getting ready for the Olympic mountain bike race. The source who corroborated the Allert presentation said this plan to stay in Andorra was agreed between team and rider, but Pidcock was the only member of the Tour team not to join the camp on Teide.

The team has tried to accommodate Pidcock's quirks, at least publicly. “He’s obsessed with winning, he’s a winner,” Cummings told the Netflix cameras. “You do need that ruthless streak. It’s just how we, as a team, manage that.” Ellingworth concurred: "With a character like Tom you can sit them down and tell them, ‘This is the path.' But you’re not going to change him. So you’ve just gotta work with him in a different way. But quite often the legs will do the talking.”

Heading into the 2024 Tour de France, the question dogging the team was not how Pidcock would fare this time around, or how he would slot into a Tour team that also contained Tour winners Bernal and Thomas and rising star Rodriguez. On the lips of pundits and fans was a far simpler query: where was Steve Cummings? The head of racing was missing from his usual spot in the team's Tour de France race car.

Ineos said he would be “supporting Zak [Dempster, another DS] and the team remotely”, but Escape was told by one person close to Cummings that the sports director’s day-to-day role at the Tour was limited at best. Indeed, during the Wednesday of the final week of the race, he decamped to southern Italy in his campervan for the extended holiday he usually takes post-Tour. He was subsequently not present at the Deutschland Tour despite being on the initial list of attending sports directors. In fact, he had not worked at a race since June's Critérium du Dauphiné.

Officially, the word was Cummings had not been suspended nor placed on gardening leave, and multiple sources say the Briton was none the wiser to his current status nor his future. “They just told him that he can’t go to the Tour without enlightening him or anyone else." the source close to Cummings said. "It stinks and it’s toxic.” In early November 2024, Cummings announced on his LinkedIn that he had left the team. Ineos made no public statement about the departure of one of its departmental heads.

One theory was posited: Cummings may have irritated team management with his combative response to a Road.cc journalist at the Critérium du Dauphiné in June when the reporter took videos of the new Pinarello Dogma, a reaction which gives off the impression of a staff on the brink.

But our reporting points to a much more likely explanation for his benching and then departure less than a year after assuming the lead director role: a severe breakdown in trust, cooperation, and communication with Pidcock. Cummings was dispensed of his Tour role just a week after the Netflix Unchained episode highlighted the tension between the pair at the 2023 edition. On the eve of the 2024 Tour’s start, when Cycling Weekly asked Pidcock how Cummings’ absence would affect the race, he responded: “Better. I don’t think it’ll have an impact. Things change, it’s not really for me to comment.”

The root cause of the fractured relationship, according to one source, is that Pidcock had taken umbrage to Cummings telling him he was never going to be a Tour de France winner as long as he didn’t dedicate his life to the road. "Steve tried to bring him back into line but it backfired and as a consequence it’s Steve who’s paying for it," they said. "Ultimately, Pidcock doesn’t like Cummings, and Cummings doesn’t like Pidcock.”

Pidcock won that round, but tensions finally came to a head two days before Il Lombardia, which was supposed to be his last road race of the season. Instead, the 25-year-old announced less than 48 hours before the start that he had been deselected for the race. In a post on Instagram that sounded equally hurt and puzzled, Pidcock said he was in great shape and looking forward to leading the team at the final Monument of the season.

Further details were not immediately forthcoming, with sports director Zak Dempster telling Cyclingnews in Italy, "It was a management decision on the final team, that's their right."

Whether Dempster knew more or not, that's not exactly an explanation, which one Ineos senior staff member says contributes to the ongoing public fascination with what’s actually going on behind closed doors.

“I can only say that if I make a decision, I inform people about my reasoning,” they said. “In every decision I make I would say why I made that decision and I would give information as to why I made a certain decision to the people involved and the people around. They need to know why. That’s not happening.”

The evening of the Lombardia announcement, multiple journalists began to hear whispers that Pidcock had been sacked by Ineos Grenadiers, a rumour dismissed by his agent at the time. That next week there was a huge push from Q36.5 to bring Pidcock into the fold, but any potential deal fell through and – for now, at least – Pidcock looks set to remain an Ineos Grenadier with three years left to run on his contract.

The anatomy of Skyfall

Whatever role Pidcock has played in Ineos' dysfunction, the team's troubles are certainly not all laid at his feet.

There is notable displeasure with the new hierarchy of Allert and Drawer. “They’ve gone down the typical route of thinking that it doesn’t matter if they’ve got people involved not from a cycling background if they’re good scientists or technologists, but actually it does matter," one source said. "Look at UAE: everyone in their management team knows cycling and look at the success they have. You need people at the top who understand what the sport is about, who know this business inside out. They haven’t got that. The whole thing is a complete and utter mess.”

This same person admitted that Drawer at least has a vision he is trying to execute, willing to shake things up and make changes. "It's at least a solution."

Allert, on the other hand, came under specific criticism from one WorldTour colleague: “They have failed terribly and it starts with the general management. Someone didn’t do their due diligence [on Allert]. He’s a good talker, but he’s a disaster.”

That view is not universally held. Ben Williams led the performance team at Ineos Britannia sailing since 2018 and joined the cycling team in late 2021 for the following two years. He left Ineos Sports Group in August 2023 and is now the director of high performance at the Brooklyn Nets basketball team.

“People always have their own account of things, but my account is that John and Dave have a very clear vision of what they want to happen," he said to Escape when told of complaints about the team's management style and structure. "It’s very easy to judge strategy in the early years when things are new and relationships are developing, but I very much understood the long-term project [of the cycling team] and that it wouldn’t happen overnight. You have to accept that high-performance sport is very difficult and you have to be patient."

But even Williams acknowledged the team is in a transitional period. "Ineos Grenadiers is coming to the end of an era of having a powerful, strong, and winning team, and some athletes are getting older – they can’t go on forever," he said. "At some point, you have to reset, find new ways to win."

The question is how well the team is equipped to do that. The corporatisation of the team brings to mind Geraint Thomas’ words to The Guardian in July when he said the team was run “like a coalition government.” He added: "Before it was a lot more straightforward with Dave at the top. There was clarity with everything. There was a simple process whereas now it’s got a lot more complicated. You need a majority. Even if you didn’t agree with stuff [before] at least there was a clear ‘boom, boom, boom’ – that’s it, move on – rather than this grey area.”

This speaks to what a former employee said was Brailsford’s modus operandi, focused on getting staff to sprint to goals as part of a nimble organisation that was best-in-class.

“Dave would be like, ‘You need to sprint this week,’ and the guys have been sprinting the entire season to work late, start early,” a former employee said. “Everyone is tired and fatigued and there's only so long you can push people to sprint before they're fucked and I think that's kind of an approach within the team.”

Under Brailsford, staff were willing – especially when paid well compared to other teams – to put in these extra hours starting early and working late, and along with the clear leadership and pull of their boss saw the reward in their efforts through the victories and dominance of the team. However, with the new corporate culture and bureaucracy getting in the way, staff reached a limit where even if they were pushed further, it wouldn’t deliver any better results.

Still, were you to canvas the entire WorldTour peloton, there would be many teams, sports directors, staff members, and riders who would trade Ineos’ specific brand of chaos for their own. The British team operates with a much larger budget than most of their rivals, and still boasts the fourth-most UCI points of any team for the most recent promotion/relegation period starting in 2023.

If there's cause for hope, it's in the form of riders like Rodriguez, who is just 23 and who in October 2023 signed an extension through 2027 to fend off interest from Movistar. According to a former staffer, Rodriguez's training and testing data show he has an aerobic capacity up there with Vingegaard and Pogačar, but his anaerobic capacity is so far off that it holds him back. According to the staffer, the team has not addressed that issue properly.

Similarly, Bernal is estimated to be back at his previous Tour and Giro-winning level from before his life-threatening crash, but the game has moved on and a solid plan is needed for how to elevate him further from his previous limits.

Decreases in performance have not been limited to Ineos' athletes. If there's been a revolving door for riders the last two years, the same has held true for sports scientists. A closer look at the timeline of those who've led the performance support team bears closer resemblance to Hogwarts' defence against the dark arts position: Scott Drawer came in for two years in 2016 and left. Paul Barrett came in for two years and left. Ben Williams came in for two years and left. And then Scott Drawer returned again.

Why?

An employee who has since left the team suggested that talented people come in, watch for a year and then try to improve things before realising they can't and so leave.

In 2023, Williams and a training scientist called Teun van Erp, whose job was to check and challenge coaches on their approach, both left. One source told us coaches did not respect Van Erp, one of the most published physiologists in the field, and wouldn’t take on board the advice he was being paid to give. Van Erp is now employed by Tudor Pro Cycling.

Williams refutes this was the case during his time with the team, highlighting the cross-sport communication and creativity between various teams in the Ineos Sport Group. Including at monthly collaborative meetings, “there was a lot of crossover between aerodynamics, hydraulics, fluids, electronics, engineering,” he said. “There was a very clear collaboration between the two sports and we’ve seen the success of that recently with Britannia qualifying for the America’s Cup."

Williams pointed to Dan Bigham's and Filippo Ganna's Hour Records – on which he worked extensively – as further evidence the team remained at the forefront of sports science. "Pre-cooling, cooling, bi-carb intake, these things that Pippo and Dan spoke about as being crucial were being used by the Britannia team,” he said. “Dave [Brailsford] has a very clear mindset that we all should share a high-performance strategy and best practice. All teams across the group made sure we were at the forefront of sports science, medicine and also from a tactical perspective. We had a strategy in place where we could have peers review our work to enable us to learn and challenge one another and pick up what other sports were doing."

The problem with that assessment is one of the marquee sports science names to depart was none other than Bigham, the team's performance engineer, and the split was over what are often termed philosophical differences.

“It’s not particularly a me versus Scott thing at all,” Bigham told The Telegraph of his relationship with new boss Drawer after announcing he was leaving Ineos Grenadiers after this summer’s Olympics to join WorldTour rivals Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe. “It’s more just how I see performance. How I want to do performance is not particularly aligned with how Ineos wanted to go about it. I wanted more autonomy, more ability to action my ideas. And I wasn’t really getting that at Ineos.

“I feel that a lot of performance we’re leaving on the table and that frustrates me because it’s clear as day we should be doing things a lot better. Let’s be honest, Ineos are not where they want to be, not where they need to be and the gap is not small.”

Such is the space between where Ineos used to be and where they are now that in May Allert called for an abandonment of the team’s famed marginal gains approach in search of maximal ones.

The "smart people" who left, in the words of the former staffer at the top of this article, "were the key people that built Sky/Ineos up into what it became. Then there was a raft of people left behind to step into the vacated roles, who were maybe hanging onto the coattails a bit, or maybe weren't the decision-makers or privy to the information that built those decisions, instead relying on the processes they witnessed but not the change that got them the process, instead just repeating the same things without understanding it was the challenging of what was happening that won them bike races. A copy and paste rather than figuring out what was coming next.”

Of course, performance doesn’t solve everything. You also need the riders. Unfortunately, in today’s peloton, if your name isn’t Tadej Pogačar, Jonas Vingegaard, or at a push Remco Evenepoel, you look as likely to win the Tour de France as someone off the street who's been dropped onto the start line.

It’s an open secret that Ineos has been sniffing around Evenepoel for the last couple of seasons, trying to lure the Belgian to their team with a big-money buyout – Evenepoel is under contract through 2026 – in a deal that would also line the pockets of Soudal-Quick Step team boss Patrick Lefevere.

These manoeuvres, and the contrast to penny-pinching elsewhere, irked team staff, according to one former employee. At the Tour de France in 2023, they said, team staff had to deal with the slow response to replacing a vehicle with broken aircon, bureaucracy forcing them to melt in the July heat even as their billionaire backer meant money and impetus weren’t a problem when it came to trying to sign a shiny new rider in Evenepoel.

There are broader repercussions to this perception – and underlying reality – that Ineos is not the performance machine it once was. Repeated efforts to swing a deal carry a whiff of desperation, focusing the cycling world on the team's growing challenges in attracting top riders.

“I would question some of the recruitment,” former rider and Ineos lifer Luke Rowe – who will surprisingly retire into a sports director role with Decathlon-Ag2r La Mondiale next month – said on his Watts Occurring podcast. “To win the biggest bike race in the world you need the best individual and that’s something that Tim Kerrison always said when we were at training camp in Tenerife. He said we’ve got all the squad here but we need our best horse at the top of his game, which at the time, for a long time, was Froomey, for example."

Speaking about today's team, he continued, “We haven’t got the best guy in the world, we don’t have the second best guy. It’s been a slow and steady decrease from a couple of years ago. Me and you [referring to his co-host Geraint Thomas], we know the organisation, we know the people running the team, we know Jim and Dave above that, and these are not the type of people to see it go by the wayside."

“We’ve got these big goals and aspirations but let’s just get back to winning some bike races,” Thomas replied. “Let’s face it, Pog and Vingegaard are gonna be hard to topple but there are still a hell of a lot of other bike races.

“That winning mentality we had is so hard to get and so easy to lose. I wouldn’t say it’s lost but it’s waning.”

One explanation for the mystery of the missing talent is the bonus clause in Pidcock’s contract. That clause, confirmed by multiple people with knowledge of it, awards Pidcock a significant bonus for winning any WorldTour race or any World or Olympic title, regardless of the discipline, which means the 25-year-old is due a substantial cheque this winter for his Olympic mountain bike win and Amstel Gold victory.

In early November, Eurosport commentator Brian Smith wrote in a thread on X/Twitter that Pidcock's bonus structure is one of the principal reasons behind Ineos failing to sign Vuelta a España sensation Pablo Castrillo, who instead joined Movistar.

“There’s people in the organisation saying, ‘If this happens or this happens [referring to Pidcock activating his clauses], our budget is going to severely restrict the number of riders we can bring in’,” said the source close to Brailsford and Ellingworth. “Two million to one rider simply stops you buying another rider.”

Pidcock’s agent refused to comment on the record about the bonuses, his rider’s relationship with Cummings, or his wider relationship with the team. Pidcock, meanwhile, appeared at Ineos’ November camp in Manchester, so it would appear he is staying with the team – at least for now.

While there are concerns over the team’s performance ability, the other gaping hole is the absence of the sort of development pipeline that is funnelling the cream of the upcoming crop into the jerseys of the peloton’s two heavyweights: UAE Team Emirates and Visma-Lease a Bike.

Back in July, Drawer informed Cyclingnews that Ineos would finally have a development team for the 2025 season onwards. He said: “We already have a small development programme called ‘Ascent’ and we’re going to scale that up. Our owners are hell-bent on developing our own talent. We’re not going to buy the top guys in, we’re going to develop our own.”

Several agents, however, told Escape that no riders have been recruited for any development team. “It’s week four of September, and if there is a plan for one, then no-one knows about it,” one said. “[Ineos] are massively the black sheep because without a development team, you’re limited to the number of younger riders you can bring through. Maybe we’ll see it in 2026, who knows. But you look at how well it’s working for a number of rival teams and it’s outrageous that Ineos still doesn't have one.”

Former Team Sky rider Peter Kennaugh was as puzzled as anyone about why Ineos doesn't have a development team. Kennaugh is now team manager of Trinity Racing, a Continental team that has helped launch the careers of Pidcock, EF’s Ben Healy, and Ineos’ Ben Turner, as well as various other young riders now in the pro ranks, and is ideally situated to be part of that pipeline, if one existed.

“I’ve not heard anything [about the Ineos U23 team]. I’ve said it for years while working for Trinity that there is a British WorldTour team right there and I find it amazing how they just allow all these other teams to jump ahead of them," Kennaugh told Escape in late September. He said Ineos has "zero relationship" with Trinity for recruiting purposes, and has also entirely missed the trend of other WorldTeams starting their own programs.

"It’s literally because they’ve all got development teams, they’ve got this ability to sign up-and-coming talent,” Kennaugh said. "It’s probably the biggest reason why [Ineos] started to fall behind. If you look at riders who are 18, 19, 20, no-one wants to go to Ineos – all the talk is about going to Visma, Bora, UAE. It’s completely different to how it was five, 10 years ago. If you don’t have that [a development team], how are you going to get the best riders?"

In each of the last two transfer cycles, roughly half of Visma's incoming riders have come from its development team, including a 19-year-old Briton, Matthew Brennan. UAE Team Emirates can win old-fashioned bidding wars, like they did with Isaac Del Toro, but its Gen Z team is also producing riders like Pablo Torres, who recently signed a deal with the parent WorldTeam through 2030.

Meanwhile, at Ineos, said Kennaugh, "When you look at the signings they make, it’s not like they’re juggling things up or starting again. It’s the same old: re-signing riders who have been there for over five years. Nothing’s going to change as you already know what you’re going to get. I can’t see how they get out of [the mess].”

As reported in late October by journalist Dan Benson, Ineos was apparently in talks with Lotto Kern-Haus PSD Bank to forge a relationship between the German development squad and the British WorldTour outfit. By November, he’d spotted a post on Facebook that alluded to a partnership and soon after it was officially announced. In theory, the deal helps shore up Ineos' pipeline, but the German-focused Lotto Kern-Haus is a curious fit: in the team's 20+ years of existence, it has mostly focused on German riders, and it lacks the pedigree of other development teams. Only a few of its riders have gone on to race at the WorldTour and its most prominent former members are Max Walscheid, Jonas Rutsch, Kim Heiduk (at Ineos), Laurent Didier and Luke Roberts.

Not only did Drawer's July claim that Ineos would have a formal development team for 2025 take months to actually come to pass, that delay has still not been explained, which is something of a pattern according to a former high-level staffer. "If you don’t give an explanation, it’s all vague and then it starts to live a life of its own and everyone starts questioning things. Riders call me and panic but I can’t give them an answer and that’s not good.

“We massively miss a person like [Brailsford],” the former staffer continued. “With Dave there was a vision, a strategy, a way of working, and clear communication. It was like day and night to now. You can’t compare and everyone sees that. Even in the hottest moments, Dave would say, 'This is what’s happening.'”

But not all the problems can be blamed on Allert and Drawer. They're newly-hired hands, brought in to clean up the missteps of the past couple of years. And even restoring Brailsford might not turn around the team's fortunes. True responsibility lies higher up the food chain.

A path forward or an ending?

At the start of 2022, Ineos Grenadiers had decided to diversify, to look beyond just the Tour de France. Almost immediately this strategy proved successful, with Van Baarle scooping up a Paris-Roubaix cobblestone, although it turned out to be the exception.

Two years later, 2024 saw a return to old ways, as management decreed the team was to once again focus all of their efforts on winning the Tour de France at “whatever the cost,” as one former staffer paraphrased the order that had been passed down. According to them, the edict was made to please Ratcliffe.

Ratcliffe is a serial collector of sports teams and has had at best mixed success with those ventures, which Ratcliffe alluded to in February after his successful bid to buy a controlling stake in Manchester United. "In having bought other clubs in Lausanne and Nice, we have made a lot of cock-ups," he told reporters. Then, he sounded a warning of limited patience for any more. "At Ineos, we don’t mind people making mistakes – but please don’t make it a second time," he said. "We're much less sympathetic when they make the same mistake twice."

But the Grenadiers are Ratcliffe's first foray into cycling, which means there's a lot of room for rookie mistakes, and Ratcliffe appears to be making some of his own.

For example, while Sky was started as an avowedly British team with the express goal of winning the Tour with a British rider, Ratcliffe apparently had a bizarre desire, we were told, to win the Tour de France with a rider from his home county of Lancashire, which meant that Pidcock – who sits on the other side of the Roses rivalry border in Yorkshire – was either not their guy or the geographical boundaries of who could win the Tour for the team would have to be quietly relaxed and widened.

More to the point, if Ratcliffe is serious about winning the Tour de France again, the deal he signed with Pidcock either shows a naivety when it comes to being able to run a successful cycling team, or misplaced trust that figures such as Brailsford – who had sign-off on deals at the time of the Pidcock contract – still have the magic which made the squad so successful for so long.

Elite sport is not something that can be treated as a plaything in an owner’s hand or delivered via helicopter or chauffeur. Even deigning to limit yourself to who can win for your team is a good way to make it more likely that you won’t. Team Sky understood this better than anyone: Brad Wiggins made way for Froome, Froome made way for Thomas, and Thomas made way for Bernal.

The belief internally, one former employee told us, is that unless the team begins making strides to try and win the Tour de France again, Ratcliffe could soon run out of interest in signing off the team's estimated annual budget of €50 million a year. Although, at 14 times cheaper than the operating budget of Manchester United, cycling may provide some relative respite from the billionaire’s new favourite headache.

"There are probably 10 to 20 things you can pin it on," one former staffer said of what is the root cause of the team's malaise. Thomas has said similar on his podcast: “I don’t think there’s one thing, there are loads of things but they all add up. There’s not one silver bullet as to the reason why we’ve struggled this year for results. For now the main goal should just be as a team, we need to be the best and most strongest, most unified, we’re in it together, we’re all moving in the same direction together."

One final perspective speaks to the sort of culture that the likes of Brailsford would likely bristle at. “Compared to many other teams Ineos pay well,” the former employee said, which raises a question: “Do staff members not want to challenge the way things are done because it means more work? Or more stress? Or more potential for change that puts them in a compromised position where they could even lose their job, when sitting tight keeps them in a cushy, well-paid role? Is what links all of the riders and staff who have left the desire for what brought them to Ineos in the first place: being part of a team at the forefront of the sport that wins?"

Empires always fall. Ineos Grenadiers has gone from winning the Tour de France in seven out of eight years to having not come close for the last five editions. The rise to utter dominance has been matched by a precipitous decline in both trajectory and velocity. The upstart-challenger approach that brought them glory has been replaced by an institutional rot of people and processes hanging on to the past. The new money originally attracted by the success has ironically got in the way of performance with their own corporate systems that function in a world utterly different from that of the professional peloton. Management, rider recruitment and performance all require revolution before they can begin to chase down the teams now leading the pack.

But all is not lost.

Last week, at the beginning of November, Ineos Grenadiers gathered in the team's spiritual home of Manchester, UK, to plot their 2025 campaign and also bring a group of people together after a bruising year.

Maybe wanting to show the sky wasn't actually falling, and to project a togetherness to the outside world, Ineos Grenadiers decided to upload dozens of photos across numerous social media posts depicting a group of people enjoying spending time together: partying, bowling, attending seminars from performance coaches and kicking footballs around Manchester United's training ground.

Amongst this group were six freshly-signed riders and 30 new staff, which amounts to a third of the team's personnel turning over as we approach a new season. While many faces have changed, the goal remains the same: restore the glory of the past.

What, then, is the solution? And, just as crucially: who makes it happen?

“Barring the miraculous uncovering of a Pogačar or Vingegaard-esque talent that can excel in any environment,” one former employee explained, “is management with a vision who can execute on that.”

Sounds a lot like someone similar to Brailsford; is he coming back?

"I think he's quite happy in the football realm," came the tired reply.

Did we do a good job with this story?