Jim Crumpler has been bikepacking since before the term “bikepacking” was even really a thing. For decades now, he’s been exploring the world by bike – often with his wife Libby – both with shorter, local touring rides in Australia, and with longer, extended adventures across Europe and beyond. In that time, Jim’s seen plenty and learned a lot about riding long distances while carrying lots of gear.

He’s refined his packing technique to a fine art. He’s become adept at overcoming the many challenges that bikepacking throws your way. He’s even rebuilt wheels in hotel rooms after they succumbed to the vigours of touring.

But Jim’s latest ride – a month-long solo jaunt from Rome to London – brought with it an entirely new challenge for the IT consultant from Ballarat, Victoria: managing a damaged heart that, less than two years earlier, stopped entirely after a ride with friends.

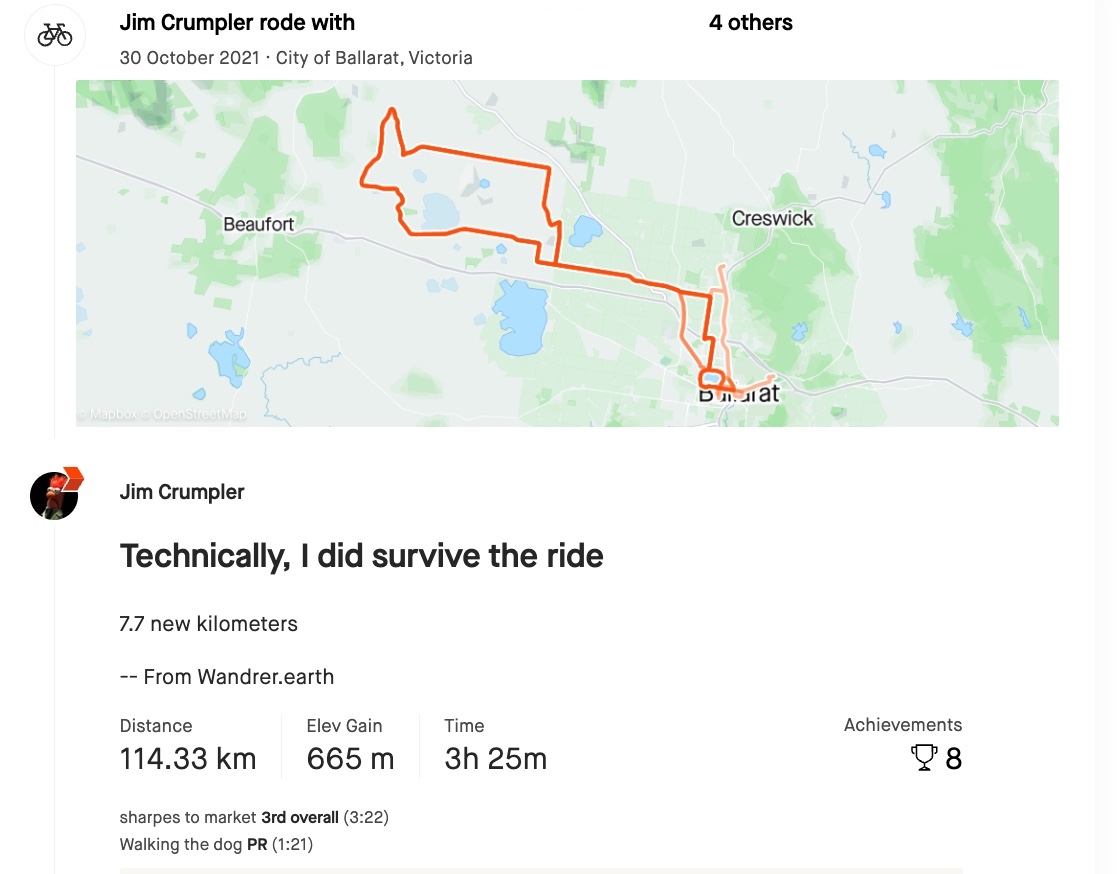

It was October 30, 2021 and Jim and co had just finished a 115 km ride from Ballarat out into the country roads out west, before looping back into town. Ride done, they parked up in a cafe in Ballarat … and then Jim’s heart “just stopped dead”. For 20 minutes.

“The survival rate is 5-10%, and luckily for me, my cycling friends (including a doctor), and another doctor in the cafe, performed excellent CPR until the paramedics turned up,” Jim wrote on Facebook a month later. “It then took four shocks, and a few adrenaline doses until my heart finally started beating by itself again.”

He spent the next five days in intensive care and a total of two weeks in hospital. Three of his ribs and his sternum had been broken during the CPR that saved his life (a common occurrence). A pacemaker was installed. “I lay on the operating table (awake), while an ICD was implanted and wired into my heart,” he wrote. “Usually I love information and knowing how things work, but this really didn’t help and I was scared shitless.”

Jim spent his 50th birthday in hospital.

While Jim was soon able to get back to gentle exercise, he’d spend more than a year trying to understand why his heart stopped like it did.

“I think it’s from sarcoidosis, which is some type of autoimmune problem,” he tells me via video call. “The doctors did a lot of fiddling around to work out why it happened. And then one of the comments back then was ‘Oh, it looks like you’ve had five heart attacks in the past.’ Well, I must’ve missed those!”

It turned out there was a bunch of existing damage to Jim’s heart, which, on the day of his cardiac arrest, prevented electric signals from propagating through his heart as they should have. But as for the initial cause of that damage? The doctors were never able to give a full explanation.

But, with a pacemaker/defibrillator installed, Jim was given the all clear to build up his riding again and return to the sort of cycling adventures he’s long enjoyed. But it wasn’t as simple as just getting back on the bike and going.

“It’s pretty scary,” Jim says. “In the past there’s be an association between doing some hard cycling and dying, pretty much, so that bit is my own personal battle to say, ‘Yeah, ‘I’m going to do this.’”

On Facebook, Jim described his recent European solo adventure as a “physical and mental health boot camp, and a test to see what the new me was capable of”. The inspiration for the ride itself came from an old cycling friend from Melbourne.

“He lives in London now and he’d pop up on Zwift and we were messaging each other … and he goes, ‘Let’s do a ride!’” Jim says. “And he tried to convince me to do the Nullarbor and I said, ‘No, that’s gonna be really boring.’ So, given he lives in London, we thought ‘Oh we’ll ride to his place for a beer’, with the starting point being … we came up with all these ideas, and one was starting in Helsinki and other ones just started somewhere in Spain.”

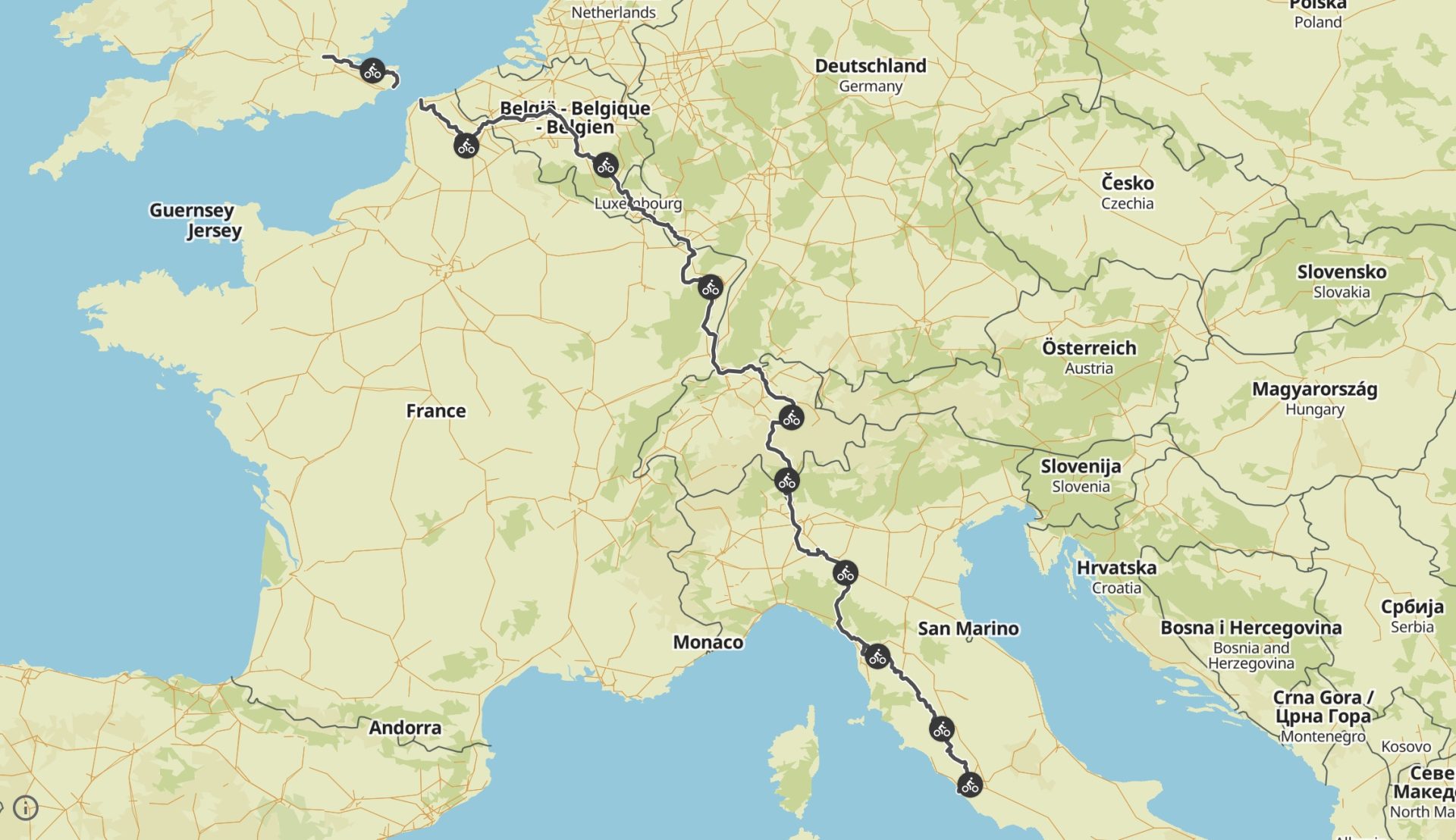

In the end, Jim chose Rome as a starting point, following the reverse of an established international cycling route called EuroVelo 5, a route that itself was inspired by a road once travelled by the Archbishop of Canterbury, ‘Sigeric the Serious’, in the 10th Century.

Jim wouldn’t normally do a ride like this on his own, and that wasn’t the plan to begin with here either.

“We had probably about six people interested, and pretty much everyone bailed, including the guy that originally convinced me to go,” Jim says with a laugh. “So I ended up going by myself. I don’t bail.”

Jim says that the ride itself was a little lonely at times, but that it forced him to speak to a lot of people along the way, which he appreciated. But there was a bigger challenge. As well as riding around eight hours a day, Jim had to handle all of his own logistics.

“How do you go into a supermarket without getting your bike stolen?” Jim says. “There might be $10,000 worth of gear hanging off your bike and you can’t bring it all in. So you gotta just grab your passport and some important electronic gear and take it in and hope the rest doesn’t get flogged. Normally, when you’ve got others, one person sits outside and one person runs in.”

And then there was accommodation.

While booking each night’s accommodation in advance might have saved time, doing so would have come with its own significant downside.

“In my experience that just doesn’t work; it becomes really stressing,” he says of having to ride a predetermined distance everyday. “There’s so many things that are unpredictable with mechanicals and heat and health.”

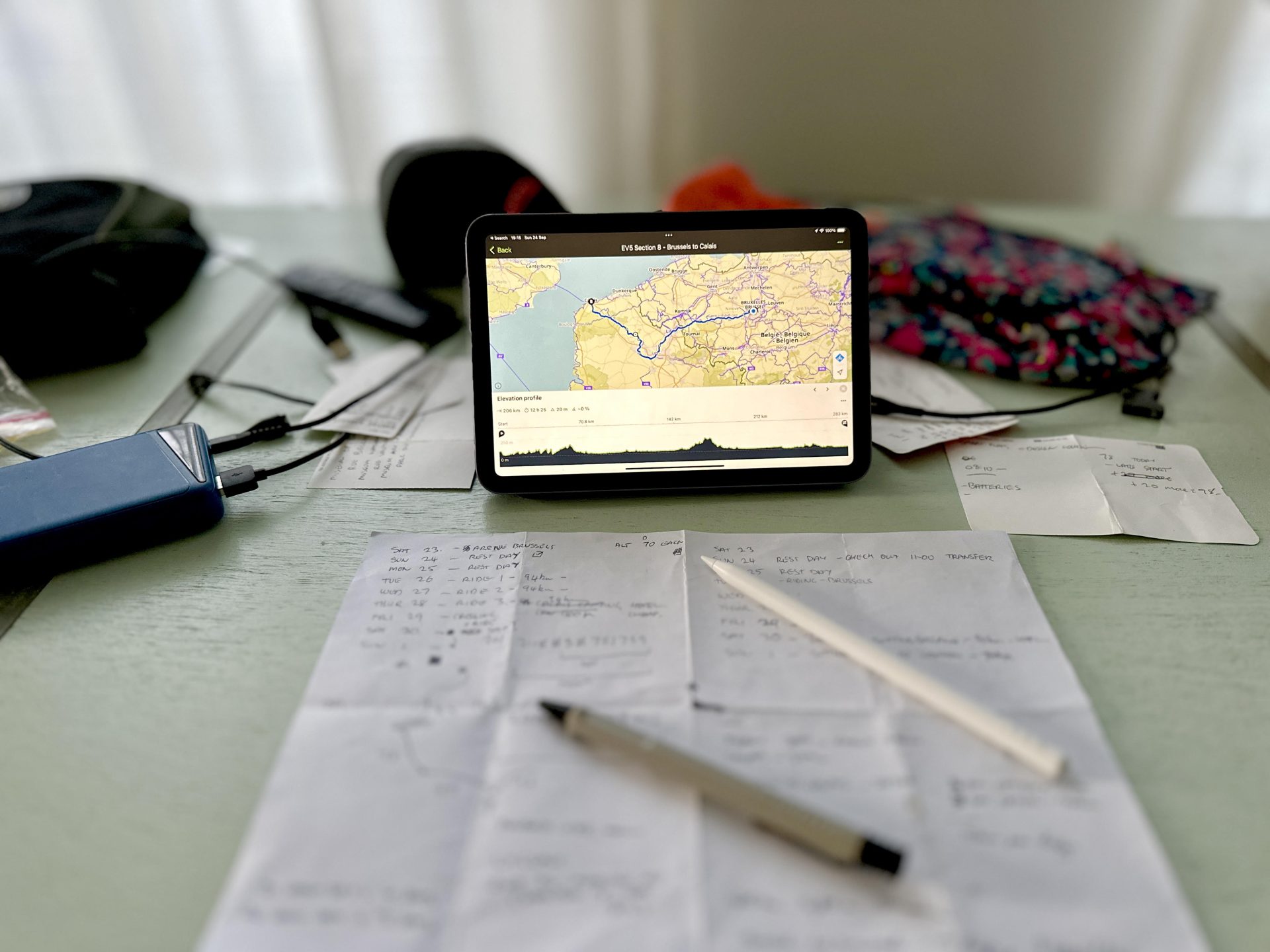

Instead, Jim organised his own accommodation every day, as he went.

“You kind of get halfway through the day and you go ‘This is how I think it’s going. I’m feeling good. I reckon I could do 95 km today,’” he says. “And halfway through the day you start aiming for a particular town, then you start researching at lunchtime. You might pull out the iPad and do a bit of research for accommodation, trying to find a tent site, and you start directing there. And if you can find something, you aim for that.”

Jim tried to keep accommodation costs as low as he could, opting to camp wherever possible. If he couldn’t find a campsite, or if he’d been camping in the rain for a few days and needed a break, he’d find a cheap hotel or B&B.

“Usually in the hotel you spread your tent out everywhere and dry all your crap,” he says. “You’re trying to find little heated towel rails to dry all your clothes.”

While Jim is right at home on a carbon road bike for racing crits, he knows from experience that touring demands something a little more appropriate.

“This was a heavy barge of a thing,” he says of the bike he took on his European adventure. “It’s a classic touring bike – it’s a Co-Motion, which is a custom bike manufacturer in the US; I think they’re somewhere in Oregon. It’s a Rohloff- based thing, which is an internally geared hub belt drive – a heavy steel thing that’s designed to carry craploads of weight.”

With a history of adapting and modifying bikes, Jim wasn’t afraid to tinker with his Co-Motion either.

“This one was supposed to be, you know, 700C wheels and they were too narrow,” he says. “So I put 27.5s in it and actually bashed these dents into the frame to try and fit the tyres in; I dimpled the chainstays and made the tyres fit.”

Loaded up, the bike weighed around 40 kg, set up with a very upright position to reduce neck and arm fatigue. The low gears allowed him to spin freely and minimise fatigue.

“What is interesting after doing this for a month, riding 2,500 km, I came back home and I did one gravel ride and my legs hurt,” he says. “Whereas the entire ride [in Europe], my legs, my quads didn’t hurt.”

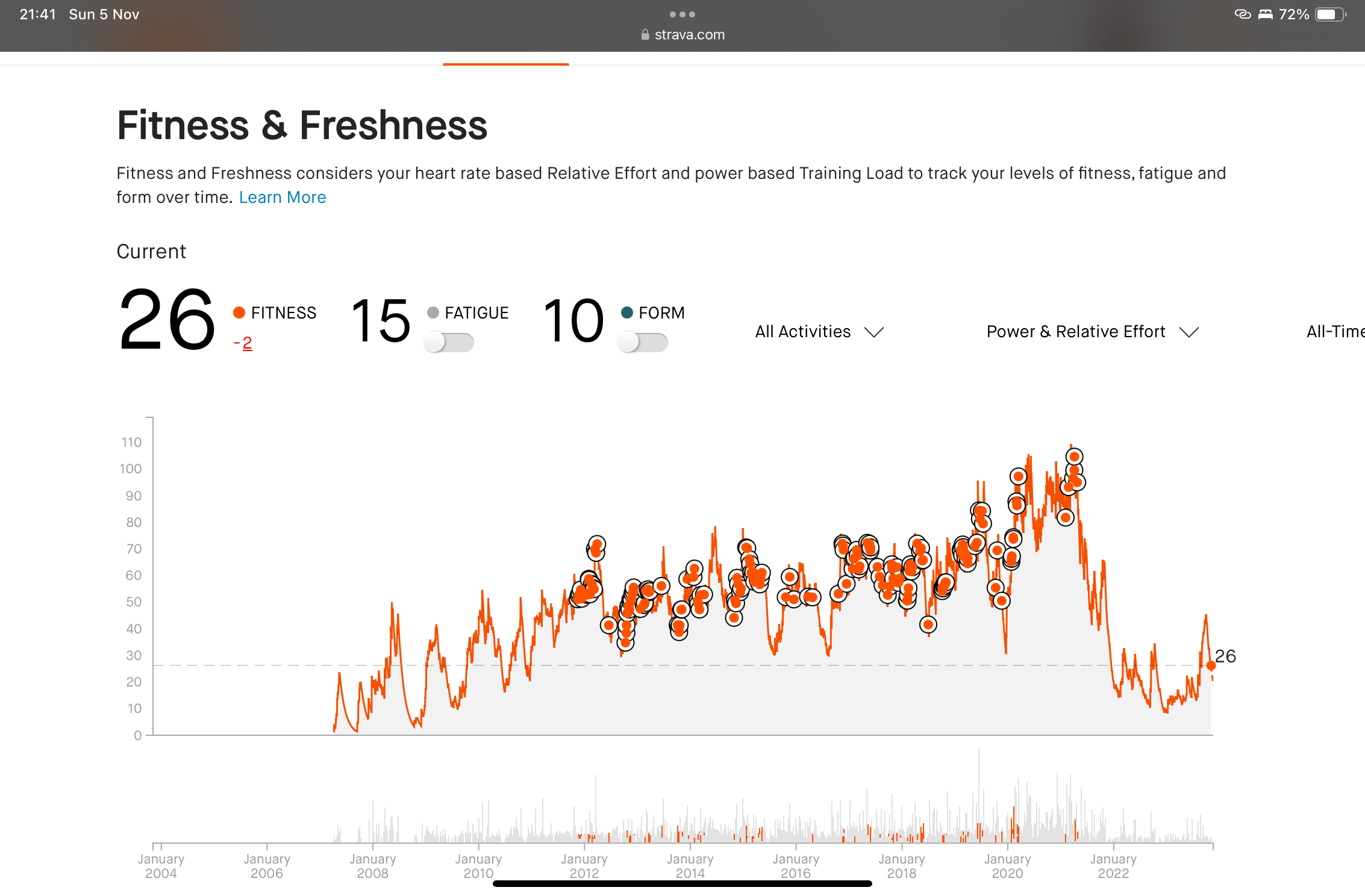

While Jim’s heart attack didn’t stop him from embarking on his adventure, it certainly affected his planning and day-to-day approach. For starters, he was the least fit he’d been in 20 years.

“I just thought I’d go anyway,” he explains. “And you’ve always heard the term ‘ride into fitness’. It’s a real thing. You spend the first two weeks just taking it easy.”

Jim had some other constraints to work within.

“I’ve got an exercise cardiologist who gave me three rules, which is: don’t get my heart rate above 135*, do not get dehydrated, and watch your electrolytes.”

He broke all three of those rules on the first day of his ride, thanks to the fact he wasn’t heat-adapted to the warm weather in Italy.

“I got straight off the plane, it’s probably 38º C or something silly in Rome, and I thought I’d just ride to the other side of the city from the airport,” he says. “I got dehydrated, probably had heatstroke, my heartrate wouldn’t come down all night.”

(*This is lower than normal because the beta blockers he’s taking drop his heartrate).

Jim settled into a more manageable rhythm, but it took a while for him to feel truly comfortable.

“The first week I was absolutely rooted,” Jim says. “I was in Italy, it was so hot, and I really suffered, and I could only go about 65 km a day. And it was pretty hilly and all the towns are on the top of hills.

“I think I managed to do five days and then I was pretty stuffed, so I had a rest in Siena. And then from there, I could get further and further every day. After about two weeks, I was doing about 95 km a day. And I could do nine days straight.”

When it came to managing his heart, Jim also had his meds to consider.

“I had this whole bag of medications and one of them … I actually planned this in advance, I knew this would occur, but my blood pressure would drop due to my expected weight loss over this thing,” he says. “We knew that if my blood pressure had dropped due to weight loss, that I had to change my dosage for some of my drugs to not get dizzy and pass out – that actually did happen.

“Instead of capsules, I had little tablets I could cut in half. So here I am, like three quarters of the way through the ride, sitting on a park bench in the middle of Belgium somewhere, trying to chop tablets into quarters so I didn’t pass out.”

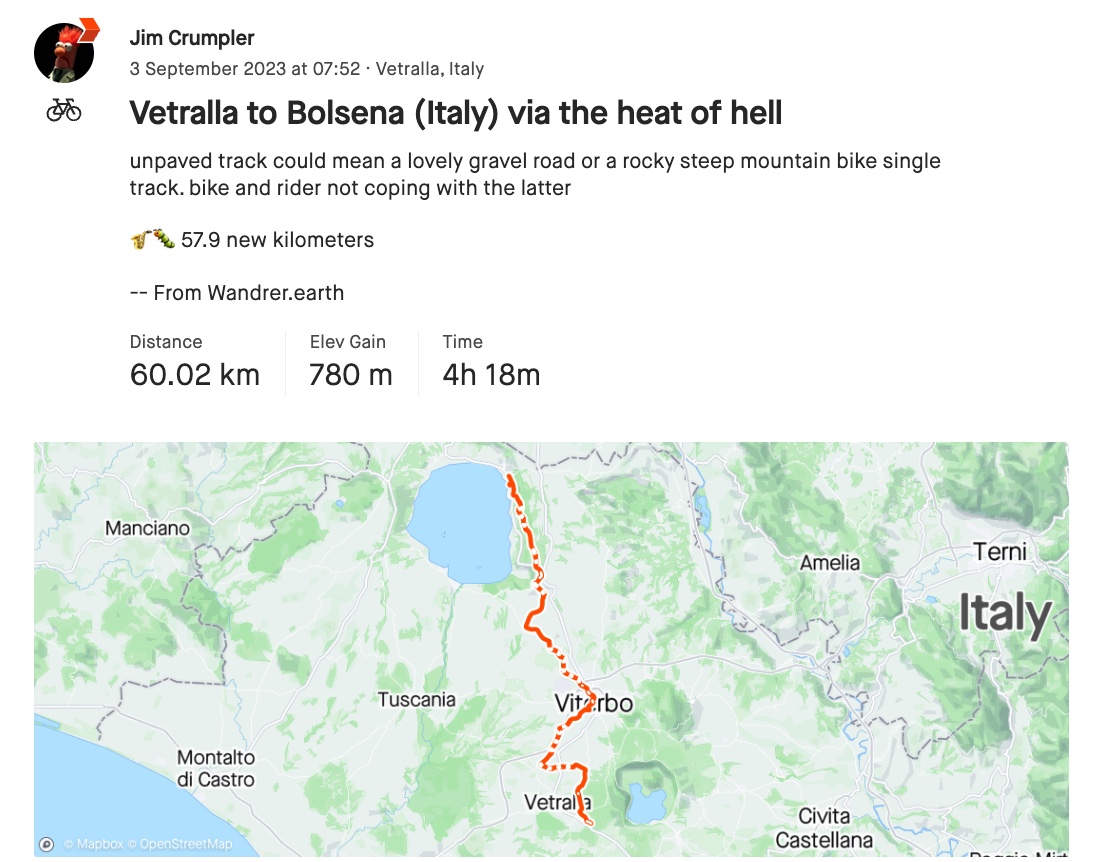

In all, Jim covered 2,200 km across seven countries with 19,000 metres of climbing. Along the way he navigated some 4,000 turns “on gravel, paths, minor roads, forests, cobbled laneways and single tracks”. In all, his ride lasted a month with five rest days spread throughout that month. His average speed each day was around 13 km/h, which included all of his breaks.

Moving forward, Jim knows he has to be mindful of his damaged heart, but he’s not stopping riding any time soon. In fact, at the time of writing, he’s currently out on a multi-day gravel adventure with friends in Western Victoria.

“I feel kind of normal – I’m just very conscious that I have to be a little bit careful,” he says. “On my Garmin now the heartrate’s always displayed on the screen and I’m always wearing a heartrate strap just to watch it to make sure I don’t accidentally get excited and go too high.”

That means Jim won’t be racing crits anymore, “but I can still do gravel ‘races’ like the Mallee Blast 1000 (or 500) which are my-own-pace multi-day bikepacking rides.” And as he’s shown, longer, slower rides – like his recent solo journey from Rome to London – aren’t just manageable, they’re the perfect way to continue doing what he loves after an almighty scare that he was lucky to survive.

“I was unfit, training beforehand was a challenge, my heart muscle is permanently damaged, root cause was never really found, and cycling was the activity that seemed to trip it up last time,” he wrote on Facebook in summing up his ride. “The cardiologists were confident this would be fine, but to say I wasn’t terrified would be a lie.

“I’m really happy with how it went. It’s a little intimidating, but very rewarding. I have an idea of my capabilities and limits again.”

What did you think of this story?