Thomas De Gendt suffered a nasty crash on stage five of the UAE Tour Friday. The Belgian Lotto Dstny rider, racing his final professional season, came down mid-stage, landing heavily on the tarmac. Thankfully, having passed a concussion test, he finished the stage with only cuts and bruises after getting a spare front wheel from his compatriots at Soudal-Quick Step.

The sight of De Gendt’s bike leaning against a roadside barrier, tyre half dismounted, sealant everywhere, along with a tangled and broken foam insert spurred a collective “WTF” comment in Escape Collective‘s Slack and across the internet. So what exactly did happen? The most likely explanation is an out-of-spec hookless tyre and rim combination was at least a key contributing factor in the crash and maybe its direct cause. And that highlights a major issue that anyone riding a hookless road wheel system should know about.

Soudal staff stopped to assist the former Quick Step rider, as De Gendt’s own Lotto team car was farther up the road servicing a teammate in the breakaway. De Gendt took to Twitter after the stage to thank the Soudal team, and indicated he didn’t know what exactly had caused the crash, asking if anyone had footage of the incident as he “would like to know what I hit with my front wheel.”

But it is highly probable he didn’t hit anything; rather a mismatch in tyre and rim dimensions may have caused his tyre to suddenly blow off the rim. As seen in the video above, the crash takes place on one of the Emirates’ typically wide, smooth highways. There’s no sign of debris or a pothole, and De Gendt appears to jerk abruptly to his right before falling heavily, which doesn’t look like the kind of crash caused by anything in the road.

The answer isn’t entirely clear; it is always possible De Gendt may well have hit something on the road, but It’s equally plausible De Gendt’s own hookless wheel and tyre combination was the primary factor in the crash, and at very least exacerbated the issue if it was the case De Gendt did hit something.

Unlucky? Yes. Accident? Likely not.

Lotto-Dstny are racing Zipp wheels and Vittoria tyres this season. Specifically, De Gendt was racing with a Zipp 353 NSW and a 28 mm Vittoria Corsa Pro, as confirmed by the team. Both Zipp and Vittoria are highly reputable brands, and as such, it’s easy to assume this was a freak, unlucky accident rather than some manufacturer error. If you did assume that, you are probably half-right: it is most likely there was no manufacturer error here, but this was almost certainly no unfortunate accident.

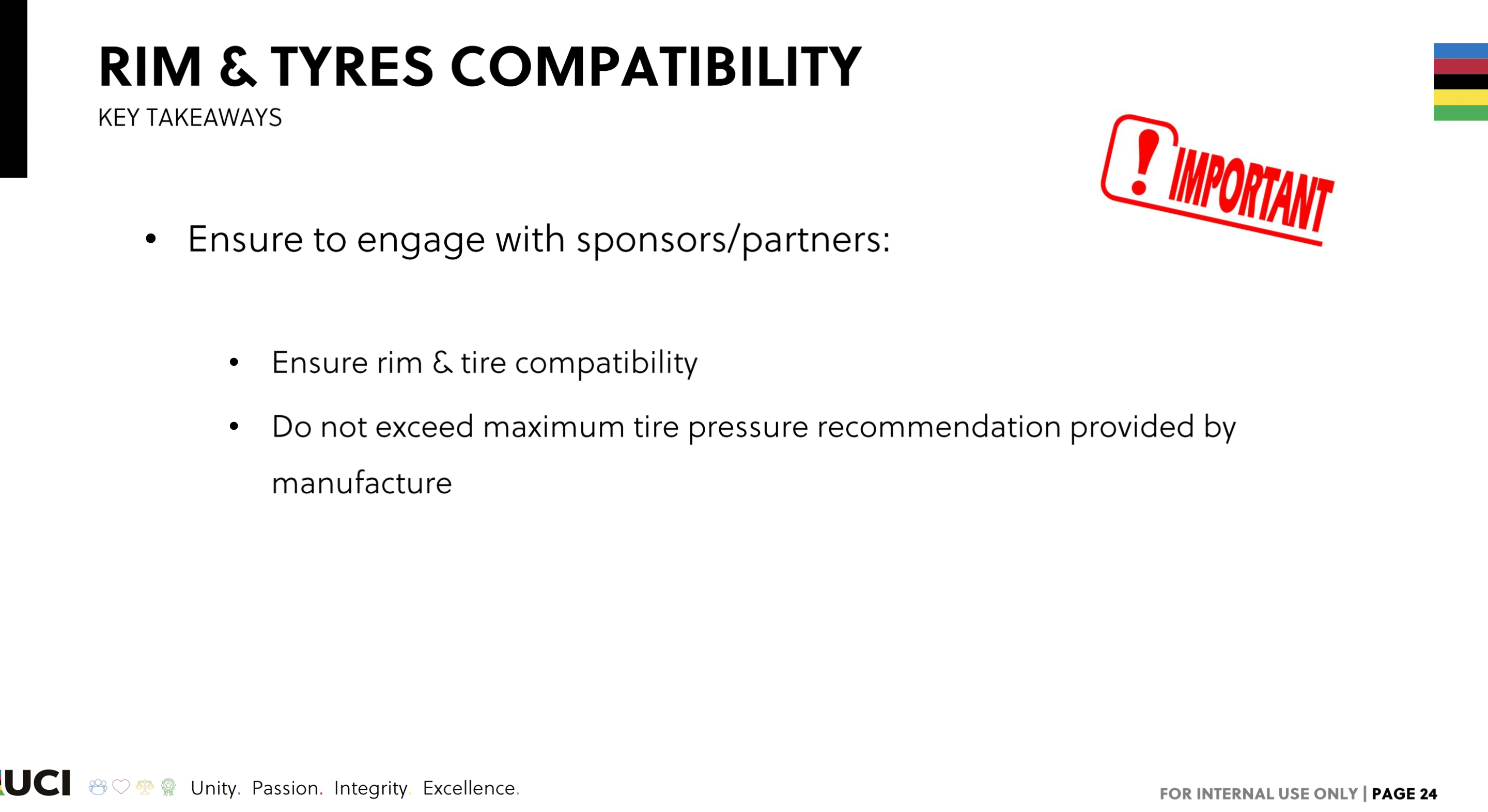

The Zipp 353 NSW features a 622×25 Tubeless Straight Sidewall (TSS) front rim profile, commonly known as a “hookless” rim with a 25 mm internal width. The redesigned Vittoria Corsa Pro, released just last year, is hookless-compatible. So, nothing to see here then? Well, not quite.

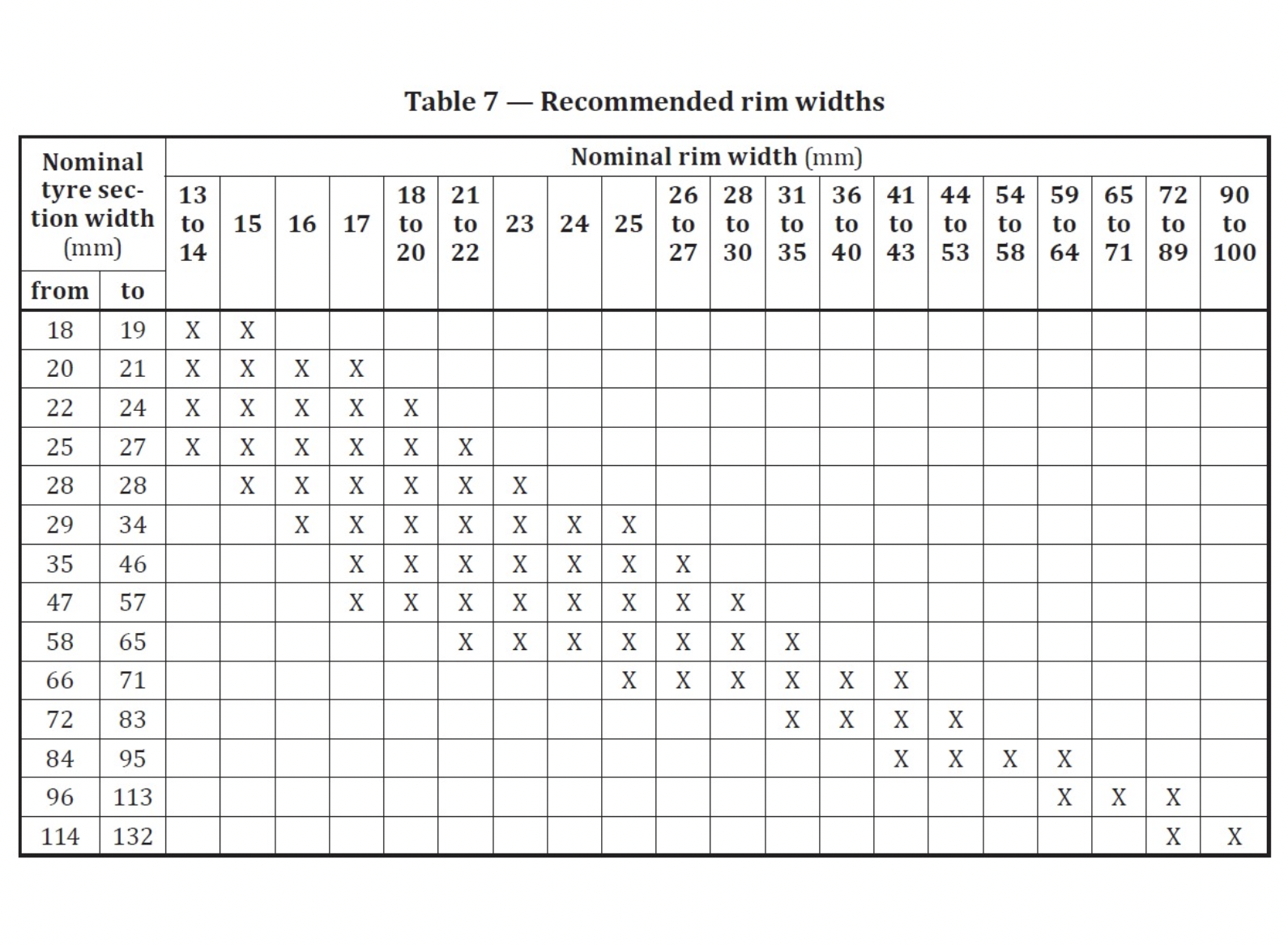

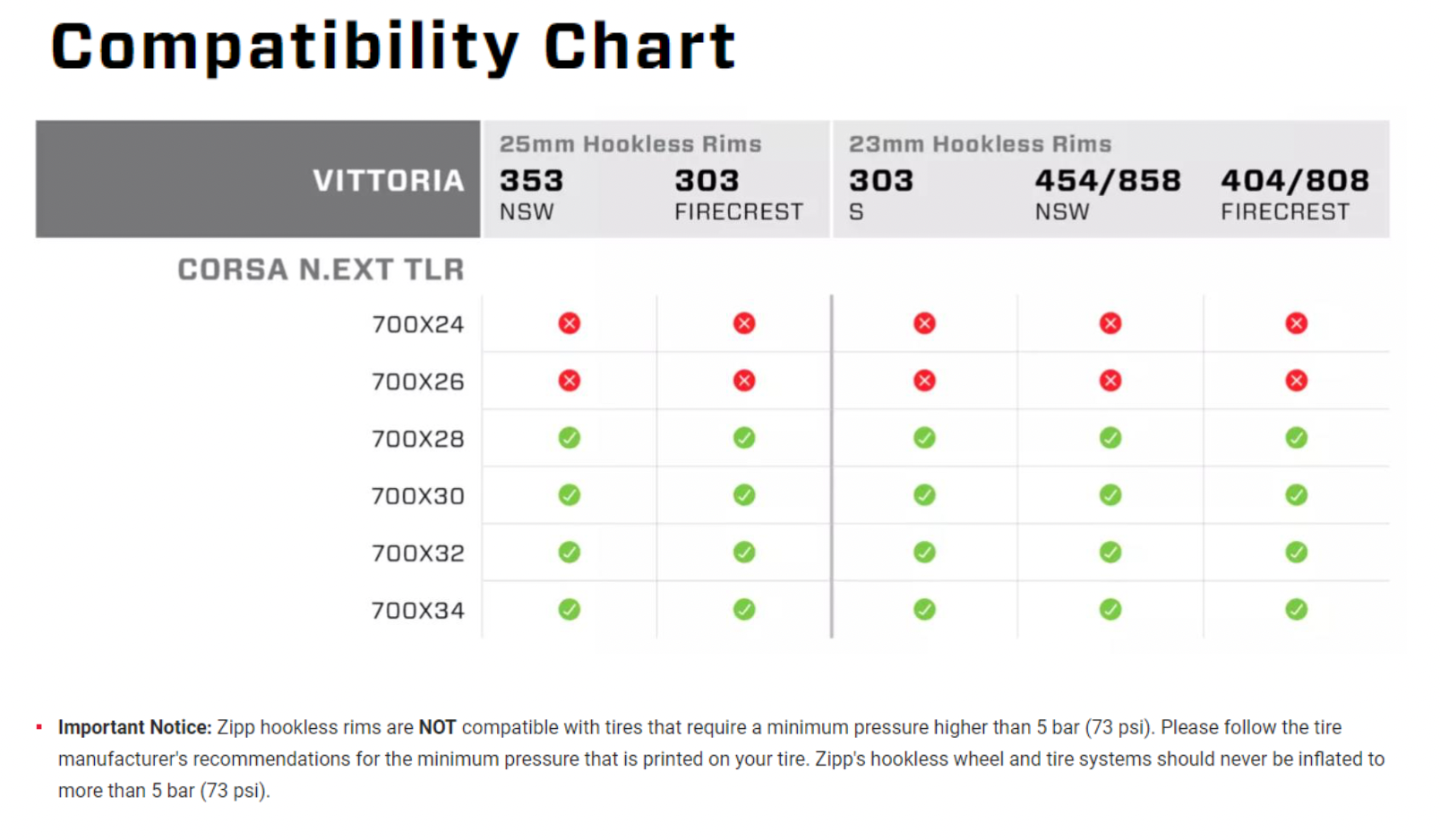

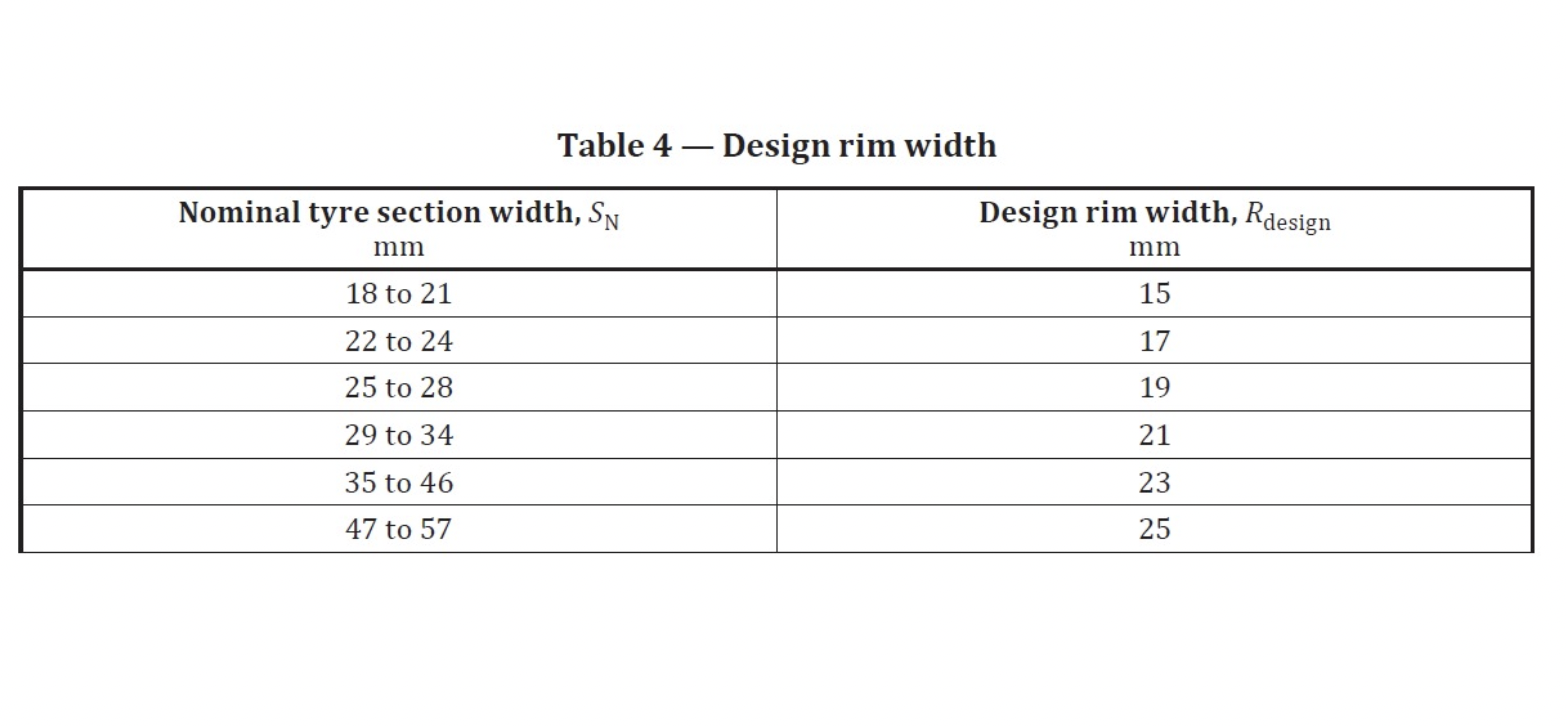

Listeners to the Geek Warning podcast might recall the crew breaking news of an update to the ISO standards in one of our very first episodes almost 12 months ago. That update to the standards, shown in the above chart, mandated that the new minimum tyre width for a 622x25TSS rim is now a 622×29 (road 29 mm) TSS, aka hookless, tyre.

In plain English, that means you should not mount anything smaller than a 29 mm hookless tyre on rims with a 25 mm internal rim. There are, of course, the usual Tubeless Straight Sidewall tyre pressure caveats also: namely, do not ever inflate a hookless tyre above 72 PSI / 4.9 bar. Further, it must also be noted this 72 PSI / 4.9 bar limit actually drops as marked tyre width increases. The pressure limit for 30 to 34 mm tyres is just 65 PSI.

It is possible De Gendt’s crash was caused, or at least exacerbated, by diverting from one or both of these standards. We don’t know what pressure De Gendt’s tyre was inflated to; it might well have been perfectly fine, although a variance of as little as 10% – well within the margin of error on many home floor pump gauges – can cause a failure.

What we can be sure of is that the Lotto Dstny wheel and tyre combination is not compliant with ISO standards 5775-1-2023 relating to “Tyre designations and dimensions” and 5775-2-2021 relating to bicycle rims. According to these ISO standards, the 28 mm tyre De Gendt was using is too narrow for mounting on the 25 mm internal rim width on the 353 NSW rim. One could argue one or both of the manufacturers should have checked which combinations the team planned to use, and perhaps they did, but the team has ultimate responsibility for its riders’ setups.

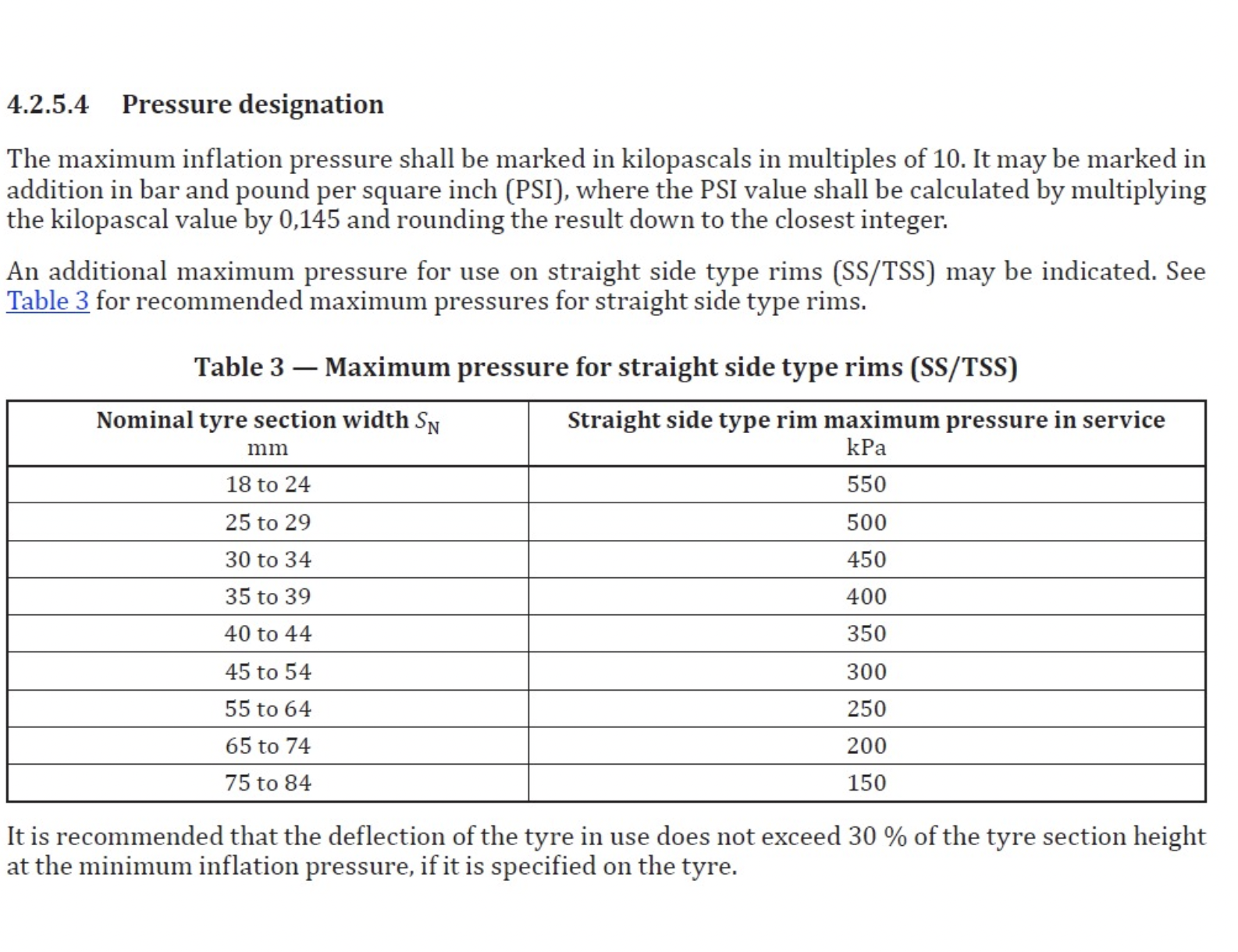

Furthermore, the UCI highlighted these rim and tyre combination mismatches to teams prior to the 2024 season and reminded them of the need to engage with suppliers and adhere to ISO standards. Escape Collective understands the UCI are planning to clamp down on such out-of-spec tyre and rim combinations, a possibility welcomed by many industry insiders we spoke with.

The wrong tire/rim focus

So if the tyre doesn’t fit the rim and the UCI has reminded teams of said issues, why are these mismatches still happening? Well firstly, it will comes as little surprise that there is a hefty dose of confusion in the hookless compatibility space. For example, contrary to the ISO standards, Zipp indicates a 28 mm tyre is compatible with the 25 mm internal-rimmed 353 NSW. This compatibility chart likely predates the ISO update last year, but regardless, Escape Collective understands those standards were updated in response to such failures and, again, the UCI may be about to prohibit non-standard-complaint combinations in UCI-sanctioned events.

The other issue is the design and intended use for various tyre widths and what I now believe is our somewhat inverse tyre selection method. As many of us have trended towards wider tyres in recent years, motivated by the promise of increased comfort, grip, and/or decreased rolling resistance, few of us have considered how said tyres interact with our rims beyond the fabled rule of 105. Briefly speaking – to avoid another rabbit hole – the rule of 105 states that the rim should be 105% of the external width of the tyre for optimal tyre and wheel combined system aerodynamics.

It’s a rule of thumb that, in the most recent episode of the Performance Process podcast, JP Ballard of Swiss Side claims has no merit. More importantly for this conversation, it’s a reminder of how we’re often focused on the wrong metrics when choosing tyre width. While many of us obsess over the measured tyre width and how it compares to the external rim width, relatively rarely do we discuss the internal rim width and how that relates to the correct tyre options for our rims.

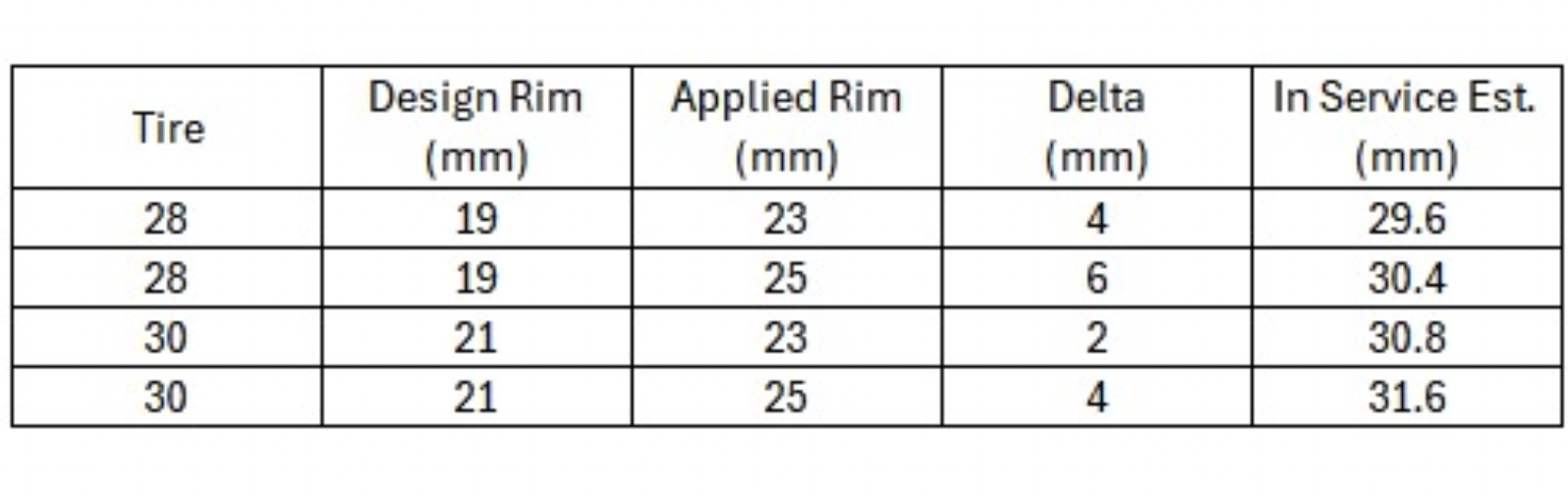

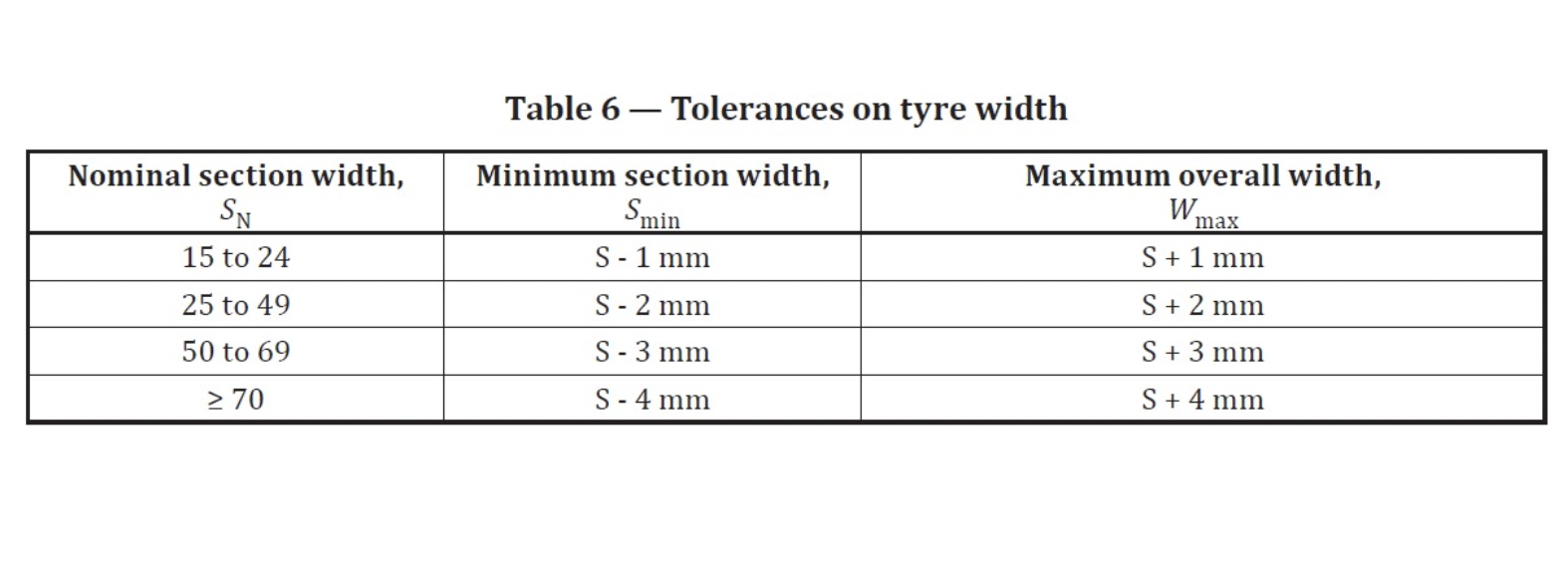

Why so? Let’s go back to the ISO standards, which all tyre manufacturers must adhere to in designing new tyres. The standard provides specific Nominal Tyre Section and Design Rim Width dimensions that each tyre must be designed around. For example, 25-28 mm tyres are designed with a 19 mm internal rim width, meaning that 28 mm tyres should measure 28mm wide on any 19 mm internal-width rim. Mounting a 25 or 28 mm tyre on a rim with a wider internal dimension, say 23 mm, will result in said 28 mm tyre expanding to 29.6 mm, as highlighted in the “In Service Estimated” width column in the table below. (Measured at 24 hours post-inflation as tyres stretch when inflated and so the 24 hour timing is to ensure expansion is considered.)

I probably don’t need to explain why it is an issue when we overvalue the aerodynamic interactions or perceived rolling resistance gains of various tyre dimensions without a moment’s thought for the dimensions that ensure said tyre mounts securely to our rims.

With this in mind, it’s also a good time to revisit De Gendt’s setup, a 28 mm tyre on a 25 mm internal rim. It’s only one mm outside ISO compatibility standards, but there’s a 6 mm delta between designed rim and applied rim widths. The result is a 28 mm tyre measures 30.4 mm on an in service estimate, beyond the +2 mm maximum overall width tolerance the ISO advises. Note, there is also a -2 mm minimum section width tolerance, highlighting the fact that tyre-to-rim interaction is not just a future wider rim/existing tyre width issue but also older rim and modern tyre mismatch issue, as I have discovered on a wheelset currently in for review.

Back to De Gendt’s (and more accurately, Lotto Dstny’s) setup, mounting Vittoria’s seemingly well-designed and safe 28 mm Corsa Pro tyres onto Zipp’s well-designed and safe 25 mm internal rims creates a user error mismatch due to the aforementioned tyre expansion. This is a problem, as a tyre stretched this far beyond its design spec can ride up the rim sidewall. This isn’t such an issue on Crotchet (marked C, think tube type, and sometimes called crochet) rims or Tubeless Crotchet (TC) rims where the rim’s “hook” effectively prevents the tyre bead from riding up the sidewall. On Tubeless Straight Sidewall it is a problem: as the tyre bead rides up the rim it has nothing to stop it riding up to the point of exploding off the rim.

Believe it or not, hooks are essentially a design redundancy element. A properly sized tyre (for the rim it is mounted to) that is correctly inflated does not “hook” onto the rim for retention. It is only the over-inflation or incorrect tyre/rim combination that sees the hook called into action.

The way forward

We could discuss the merits bemoan the use of “hookless” until the cows come home, but in all likelihood it is not going away. I sat down a few weeks back to vent my much graver concerns about hookless in general. I’d titled it “do-one, hookless,” but as I researched the article, I realised hookless per se isn’t the issue.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m still not a hookless fan and remain unconvinced on the claimed benefits. And there is an entirely separate discussion to be had on rolling resistance, aerodynamics, and performance concerns, but if the tyre answer to those is 28 mm, the wheel answer is not one with a 25 mm internal rim. This is the message we either missed or the industry failed to send as tyre widths trended up. We all wanted the promised gains of wider tyres, but no one really told us that only those with the right rim widths could avail.

My research so far has somewhat put my mind at ease if I can stick to reputable manufacturers and use not just the correct lower tyre pressures, but considerably lower than the limit the ISO standards permit.

That said, the rollout of the hookless standard in road cycling has some worrying issues for all riders: the varying pressure limits and home pump gauge accuracy issues, the relatively small safety margin for over-inflation, and perhaps most scarily, the evidence suggesting some rims do not comply with the very specific dimensions required for hookless to work safely. More shockingly, Escape Collective understands some “less than ideal” Tubeless Straight Sidewall rims measuring perfectly to spec may flex out of spec under pressure from an inflated tyre, almost certainly leading to failure, a problem exacerbated by even minimal over-inflation.

All of that is compounded by the broad lack of understanding in the market. Again, De Gendt’s crash – on wheels from a reputable manufacturer doing hookless rims right, paired to hookless-compatible tyres from a reputable manufacturer – is not a fault of hookless itself but of not following standards. It’s a consequence of teams and riders not following, not understanding, or perhaps not knowing the standards. And if UCI ProTeams, with experienced professional mechanics who can consult directly with equipment partners, can make these kinds of mistakes, then many amateur racers and riders, and home mechanics, certainly can as well.

But if standards are to be followed, they have to be widely known, and clearly, they are not. One issue: there is no central, simple compendium of information on hookless safety. Furthermore, having read this article if you’d like to familiarise yourself with the ISO standards referenced here, those will cost you CHF129 per document. That’s before having to delve into 46 pages of technical speak and the fact many might not have even heard of them before now. Right now, riders (or teams, in De Gendt’s case) are responsible for knowing a complex array of compatibilities that rely on an interplay of factors like a tyre’s printed/design width, rim internal width, and pressure, even as the information they need is not readily available.

I don’t recall ever being asked what size rim I had when seeking new tyres either online, at a bike shop, or from a manufacturer. On the other hand, I don’t recall ever visiting a motor vehicle tyre centre without a staff member checking the specific size of the tyres my vehicle required based on rim size and total system weight and informing me (not asking me) of the tyre size required. It seems to me we could benefit from a similar approach with our bike tyres.

More generally it could be a consequence of our obsession with stamped tyre widths and the promise of wider is better rather than letting the wheel in question dictate the tyre width we require. Hookless is here to stay, we could keep complaining about it (we will) but if we want to ensure those hookless tyres stay on our hookless rims it’s about time we rethink our obsession with tyre widths and start considering compatibility first, and performance second.

What did you think of this story?