The UCI has a thing about how the sport looks. Many of us do. The UCI differs because it can and often will actually do something about it.

Dylan Groenewegen and Italian accessories manufacturer Scicon were the latest to feel the UCI’s wrath as commissaries stepped in mid-stage 3 of the Tour de France and forced the newly crowned Dutch national champion to remove his new cycling glasses. Why? Officially, it is because the glasses are not commercially available. Unofficially? Presumably because the 3D-printed, Batman-esque nose covering attached to those glasses offended the UCI fashion police.

Fast forward 48 hours and the nose cover is now for sale online – for a cool €350 in addition to the glasses – and Groenewegen, aka the Dark Knight, had his mask back for stage 5.

But wait, does the UCI have jurisdiction over what glasses someone chooses to wear? New glasses come and go, and Scicon themselves have a seemingly endless list of models, but the UCI doesn’t seem to have paid much attention to them previously. In fact, its own Prototype Application Form doesn’t even list cycling glasses as equipment or textiles for which authorisation or approval is required.

That form, as it turns out, may soon be out of the sport itself, as the UCI considers regulation updates which would spell the end for prototypes in races.

'I want to look like Batman'

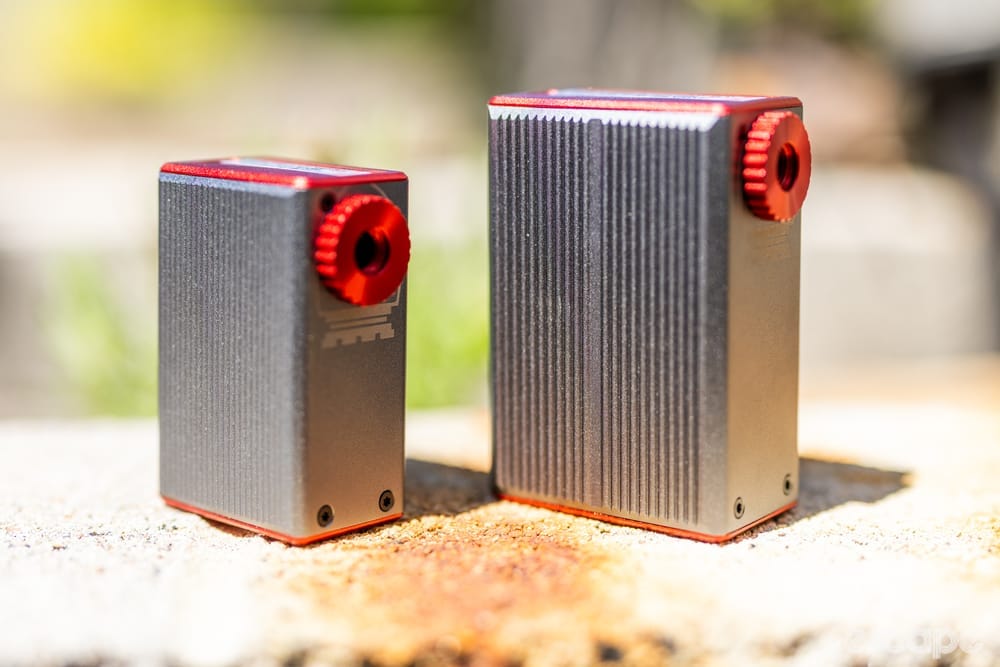

First of all, it’s not actually Groenewegen’s glasses that the UCI took issue with but the nose cover attached to the detachable nose pad. Scicon told Escape Collective that the concept stems from requests from pro riders to produce a cover to eliminate dirt and water ingress on wet days. Developed specifically for those wet days and the Spring Classics, that nose cover was first spotted on Tim Wellens on a recon day ahead of this year’s Strade Bianche.

The new nose pad is 3D-printed and specific to each rider’s nose. Scicon 3D scans a rider’s nose before an engineer spends a claimed eight hours per nose pad turning said scan into a 3D file and printing it. As for the benefits, Scicon claims it “found some aerodynamic benefits,” to the tune of a seemingly implausible “2-3 km/h, especially on the downhill,” but the brand did also admit “it depends” and it is “also about fashion.”

Entrer Dylan Groenewegen, who, having seen the glasses, told Scicon “I want to look like Batman.”

So what gives? And how can the UCI intervene mid-stage to force a rider to remove what is a trivial piece of equipment and arguably a safety item, only to roll back and allow the same rider to wear the same glasses in the same race just 48 hours later? Lo and behold, said rider went on to win a stage in the same race just another 24 hours after that – wearing, you guessed it, the same glasses.

What gives is the UCI commercialisation rule. Asked why the UCI had Groenewegen remove the glasses only to do a U-turn 48 hours later, Scicon told Escape Collective it hasn't encountered issues with the UCI in the past with new glasses but the commercial availability of this nose pad was “the main problem.”

Prototypes only

For those just joining us, article 1.3.006 of the UCI regulations states “Equipment shall be of a type that is sold for use by anyone practising cycling as a sport.” Specifically, the UCI defines equipment as “any product a rider will use in the UCI-sanctioned event including but not limited to clothing, safety equipment and bicycles.”

There is one exception, though, that is for prototype equipment, defined as “equipment which is in the final stage of development and for which commercialization will take place no later than 12 months after the first use in competition.”

If it's not enough that this definition practically reduces in-race “prototype testing” to a glorified marketing activity for products that are already destined for commercial sale rather than truly developmental testing of new products that may or may not prove worthwhile, the UCI also mandates that the use of prototypes is subject to pre-authorization from the UCI’s equipment unit before any use in competition. Said authorisation request must be submitted to the UCI on its Prototype Application Form along with the manufacturer paying the associated fee ranging from $250 to $1000 based on the product category. As Ekoi found out the hard way to Team Nice Metropole’s expense earlier this year, said form must be submitted a minimum of 45 days before its first use in UCI-sanctioned events. Reportedly, Ekoi missed the submission deadline by a matter of hours.

So, that’s that. The Scicon Mbappe mask wasn’t available to purchase and presumably wasn’t registered as a prototype. Mystery solved? Not quite.

Again, the UCI does not list glasses (of any form) among its list of specific category options on the Prototype Application Form. There isn’t even a generic catch-all “safety equipment” option on the form and as such seemingly no mechanism for registering prototype glasses.

Ignoring the fact that the head honchos at the UCI have once again picked the absolute tiniest hills to die on, a lack of a prototype application option for glasses does not absolve Scicon and Gronenewegen of any wrongdoing.

As mentioned above, safety equipment, a category which, again, glasses likely do fall into, is specifically mentioned in the list of equipment to which the commercialisation rule most definitely does apply. Therein lies the potential for confusion: glasses must be commercialised but, unlike seemingly everything else, they are not listed as a prototype option.

Add into this confusing mix the UCI’s questionable jurisdiction over which glasses a rider chooses to wear and the lack of precedence for the UCI intervening to ban glasses in the past – notably the similarly nose-covering Oakley Katos worn by stage 5 winner Mark Cavendish, among others – and it all feels a bit ridiculous.

Heck, if we want to be ridiculous, one must question where the logical conclusion of this approach is. Are the designer watches many riders now wear in the peloton considered “equipment?" Presumably most are commercially available, but is the UCI checking Tadej Pogačar's Richard Mille, and what of custom timepieces? More specifically with regard to cycling equipment, what of Mark Cavendish’s Nike cycling shoes? Nike hasn’t made performance cycling shoes in well over a decade and I don’t recall (nor could I find in researching this article) Cav’s kicks for sale online. It’s rumoured they were once manufactured by DMT, but again, a look online doesn’t throw up any matching designs.

The issue with all this is that it once again highlights a sportwide issue in that the UCI rules on commercialisation and prototypes are thoughtful, well intentioned, and failing.

There’s more

Groenewegen’s glasses are not the only product to fall foul of the commercialisation rules this week. Time trial day at Le Tour is one of the biggest and most expensive tech days of the year. Teams roll out all manner of wind-cheating and time-saving new equipment – often still, officially, in prototype phase. The manufacturers register the equipment with the UCI, and both sides lament a system that neither achieves the UCI’s intended “fair and equitable access to equipment for all” objectives nor allows the manufacturers to truly test or continue R&D work right up to the last possible moment.

Escape Collective is already aware of several items planned for use in the time trial which simply were not ready in time for the UCI’s 45-day prototype notice period. So what happens? The manufacturers are forced to list products for sale with de facto unavailable price tags, even if the rules prohibit such practice. At the core of that problem is the fact no one decides what is “de facto unavailable” pricing. Theoretically, these products might not even be truly consumer-ready or at least not “production models" in any real sense of the term.

Of course, the manufacturers are hoping for exactly that: that the often-ludicrous price tags are enough of a deterrent to put anyone off actually ordering them. But the UCI does mandate they are available “through a publicly available order system,” that any orders must be confirmed within 30 days, and that they must be “made available for delivery within a further 90 days.”

Presumably this whole thing is a nightmare for the UCI, although a nightmare arguably brought on by its own attempts to regulate the somewhat-unregulatable, and its sometimes-lacklustre attempts to do so.

No light

Perhaps somewhat worryingly, Escape Collective understands the UCI is considering further updates to the commercialisation regulations, with a UCI Management Committee meeting scheduled for September set to consider dropping the prototype option entirely. Potential new regulations could enforce immediate and mandatory commercialisation for all equipment prior to use in competition. In other words: if it ain’t for sale on race day, it is not permitted for use in UCI-sanctioned events.

That escalation may seem trivial, even necessary if the UCI wants to truly invoke commercialisation, but several manufacturers Escape spoke to were keen to point out the major issue it presents: mandatory and immediate commercialisation prohibits final testing of new prototype products in competition.

One manufacturer Escape spoke to on condition of anonymity explained: “the current framework allows for a final-proof test of any equipment prior to offering it as a finalised commercial good,” which enables the brand to discover any issues that didn't appear earlier and make refinements to the product before introducing it to us, the buying public.

But would the products we buy change, or potentially suffer without that additional testing? The same manufacturer told us, “we'll be in a very difficult situation if we find deficiencies in a racing environment with shops and distributors holding stock around the world. Regardless of how rigorous pre-race testing is, things happen in races that can't always be replicated in the lab, and having time to fully digest these issues, replicate them in the lab, create additional prototypes to mitigate a potential issue, and finally test and confirm them in both the lab and in use is an essential step in our development process".

Representing another perspective, Scott Sports told Escape in conversation at Eurobike that it never has athletes race or ride prototype equipment and all new products must pass stringent, and individualised, stress testing before a team of engineers and former riders field test new products extensively. Only after several rounds of lab and road testing does a prototype move to the next phase and its pros only ever ride production-run equipment. In short, Scott is effectively indifferent to the UCI’s plans for prototyping.

Another source Escape spoke to at Eurobike expressed concern that road cycling (the same rules do not apply to other disciplines, although the rules in track cycling are significantly more stringent) as a whole could be the real loser as manufacturers turn to non-UCI sanctioned disciplines like triathlon and gravel as areas with greater innovation potential. Drawing that to its logical conclusion, the source questioned whether manufacturers will want to invest in WorldTour teams in the future if the UCI is so restrictive they effectively cannot innovate with freedom. Or in other words … give us all new reasons to spend more money on new bikes.

We have of course heard this doom and gloom scenario touted over many years. The reality, though, is that brand’s simply cannot give up the marketing value the World Tour offers as detailed by CEO of Factor, Rob Gitelis, when earlier this year Escape investigated why modern bikes are so expensive.

“the real issue is it just gasses the whole "cool" factor from the sport/equipment which is exactly what they want to do”

To that point, Escape has also previously investigated what would happen if the entire peloton used identical equipment. While the general consensus was that a so-called ‘spec series’ is generally a good idea in theory, it would likely prove markedly less so in practice and catastrophic for the sport. Even the idea it might help with getting more kids into the sport was rebuffed by a lead development coach who explained most kids love the tech and what is actually needed is just more $500-$1,000 quality racing bikes.

All that said, as many see it, road cycling’s prototype model has arguably already descended into mostly just marketing activity in recent times. Furthermore, the UCI argues that such strict processes target its goal of ensuring “fair and equitable access to equipment” for all, ensuring that the wealthiest teams and manufacturers cannot simply roll out new performance-aiding products for the biggest events and quash the chances of lower-budget operations.

There are also no guarantees the considered updates ever see the light of day. The UCI may consider them, but not adopt them, as is their right. Seemingly the only guarantee with the UCI rules is that, unfortunately, this is very unlikely to be the last time the rules and their implementation have us rolling our eyes back in our head.

Did we do a good job with this story?