It’s May 2021 and Colnago has just sold a video of a bike for more than US$8,500. Not an actual bike, a video of a vibrantly coloured C64 that just spins around. Anyone can download the video themselves, but one person has just paid a lot of money for documented proof that they own the original copy of that spinning C64.

It’s all incredibly weird. Colnago explains that the video is actually a “non-fungible token” – an NFT – that uses something called a blockchain to track ownership. The Italian bike brand is the first big name in the world of cycling to climb aboard a hype train that’s been building speed around the world in the months prior.

The public response is one of confusion and derision. Most people think NFTs are a dumb waste of time and money that are bad for the environment. And yet Colnago will be just the first in cycling to adopt the new technology. Many other brands and individuals in the sport will follow, joining a baffling global trend.

Fast forward to late 2023 and the NFT market has bottomed out in spectacular fashion. The market was already in decline when, elsewhere in the Web 3.0 space, the giant cryptocurrency exchange and hedge fund FTX declared bankruptcy in late 2022. By the time FTX CEO Sam Bankman-Fried was found guilty of seven counts of fraud and conspiracy for his mismanagement of FTX earlier this month, an independent report found 95% of all NFTs are now essentially worthless.

So is that it? Are NFTs done? And more specifically for our purposes, have we seen the last of cycling’s brief dalliance with NFTs and blockchain technology more generally? Has a trend that many thought dumb turned out to be, well, dumb?

Before we answer those questions, let’s revisit the shortlived era of the cycling NFT and see where things are at now.

Colnago, the first mover

There were two bids on that Colnago C64 NFT that sold back in 2021. And when user MTD-01 won the auction for 3.2 WETH (wrapped Etherium, a cryptocurrency token) many incredulous onlookers correctly identified – often with great glee – that MTD-01 could have spent US$2,000 less and bought an actual C64 with a custom paintjob – a bike they actually could ride.

If MTD-01 had hopes of buying that Colnago C64 NFT and then selling it on for a profit, those hopes don’t seem to have been realised. The NFT was transferred to another user, “ColnagoLover” shortly after purchase but hasn’t been sold at any point since its original purchase.

The spinning C64 NFT.

As we’ll soon learn though, Colnago wasn’t just the first big cycling brand to dip its toe in the NFT waters – it’s one of the few that’s actually persisted in the Web 3.0 space ever since.

Bike Club NFT

In November 2021, six months after that Colnago C64 NFT auction, a new community called Bike Club NFT started making headlines. Billed as the world’s first blockchain-based cycling club, Bike Club NFT invited people to join by purchasing an NFT that would unlock various perks, including industry discounts and video chats with pro riders.

Each member’s NFT would also include a special avatar for use on social media, designed by illustrator Richard “Rich Mitch” Mitcheltson. A number of big names in the cycling sphere were involved, not least pro racer (and Escape Collective founding member) Jack Haig, and commentator Matt Stephens.

Where the response to the Colnago NFT was one of confusion and derision, public attitudes towards Bike Club NFT seemed even more hostile. Many were critical of the environmental impact of the Ethereum blockchain the organisation originally used. And while the project attracted had 1,000 members by late March 2022, the founders would soon step away from NFTs following the community backlash. Bike Club NFT became just Bike Club.

Speaking to Escape in 2023, Paul Willerton – one of Bike Club’s founders* – says he’s not surprised there was such a backlash to the NFT component.

“Digital assets didn't jive as well in certain places like the UK, for example,” he says. “There were certainly people over there, like Rich Mitch, who did see and were excited by the potential of it.”

(*Willerton is a partner at DeFeet Socks, which claims to be the “first cycling brand to attach items to the blockchain”, to help customers authenticate their purchases.)

Willerton says that people’s concerns about Ethereum’s environmental impacts were largely unfounded and that he regrets bowing to community pressure to step away from NFTs.

“The reality is, the idea that blockchain is bad for the environment or too power-consumptive is a false narrative,” he says. “Bitcoin mining can be and is being used as a lot of waste energy that would just be released into the atmosphere, like flares from oil fields, and so on – that can all be captured and used to resolve transactions on the Bitcoin network.

“In the timeframe that we were doing Bike Club, Etherium transitioned from proof-of-work, which uses a lot of electricity and CPUs, to proof-of-stake. So it became dramatically less power-consumptive. But all the blockchains are taking just leaps and strides to becoming green solutions.”

The Discord server at the heart of Bike Club is still around, but in the words of Shane Cooper – another Bike Club co-founder, and the founder of DeFeet – “nobody’s really talking”. While other co-founders have stepped away from Bike Club, Cooper and Willerton are still hopeful about reviving the community.

“We've talked about different ways for how we want to re-approach this,” Willerton says. “We're not done by any means. It would be nice to have more-accepting public sentiment, as we open that back up. We're open to looking at partnerships with different media groups who do want to offer this as sentiment changes.”

Speaking of media groups …

The Outerverse

Around the time that Bike Club was stepping away from NFTs, Outside – the former employer of this author and many other Escape staff members – launched its own foray into the world of Web 3.0.

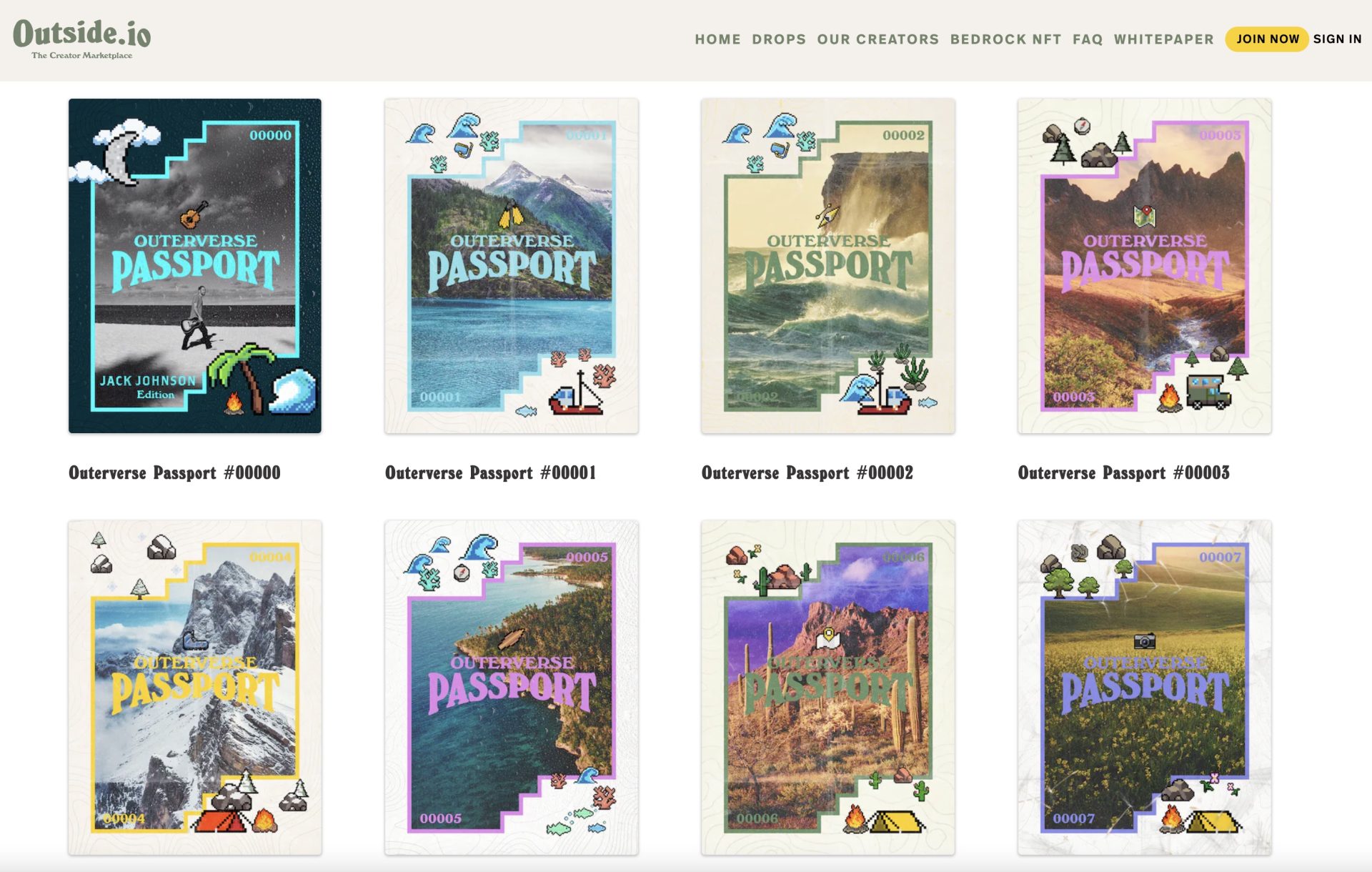

Rather than just launching an NFT collection, the Outerverse was an NFT marketplace which Outside pitched as “the first outdoor and active lifestyle NFT Marketplace committed to promoting wellness, diversity, and sustainability with the help of blockchain technology.”

It was an ambitious sell: a digital-only offering that was supposed to be both an antidote to Facebook/Meta’s vision of the Metaverse and a way of getting more people outside, away from their screens. Many people found it confusing.

The inaugural Outside NFT, dubbed the “Outerverse Passport” went on sale in July 2022 for US$300 and was supposed to give access to future NFT drops and provide “real-world benefits for the outdoors – free gear, tickets, exclusive content and discounts to your favorite outdoor brands”. Of the 10,000 Outerverse Passports available for sale, only a few hundred sold.

Of the people that bought one, many complained of technical issues. Some had trouble claiming the three-year Outside+ membership that was included with the NFT; others had difficulties transferring their NFTs between crypto wallets. Many were left feeling like Outside abandoned them and didn’t offer what they originally promised.

In October 2022, Outside launched a cycling-specific NFT drop, the Biking For All collection. That, too, failed to meet expectations. Of the 10,000 NFTs available, less than 7% sold. Outside shut down the Outerverse in November 2022, with CEO Robin Thurston admitting in a staff meeting that the project didn’t go to plan.

That decision came the day after three Escape staff members (your present author, Caley Fretz, and Dave Rome) were included in the 12% of Outside staff to be made redundant – the second significant round of lay-offs that year.

While the NFT gamble didn’t pay off for Outside, it wasn’t the only organisation trying its luck.

NFTs in the pro peloton

At the team presentation for the 2021 Tour de France, the riders of Bahrain Victorious stepped onto the presentation stage wearing a new team jersey. In a departure from the normal order of things, these weren't jerseys the team would wear during the race. In fact, the jerseys were destroyed immediately after the presentation.

With the physical jerseys gone, Bahrain Victorious minted a single NFT of the jersey which it auctioned off, with the proceeds (0.2 WETH / US$400) going to the Royal Humanitarian Foundation. As Escape’s Iain Treloar wrote at CyclingTips at the time, a greater contribution to the charity could probably have been made by selling a limited run of the actual real-life jersey, not to mention selling the original jerseys the riders had briefly worn (but were instead destroyed).

The following month, in July 2021, pro team Movistar entered the fray, selling NFTs of Alejandro Valverde’s rainbow jersey from 2018 and of the Canyon Speedmax WHR Alex Dowsett rode to the UCI Hour Record in 2015. Curiously, those Movistar NFTs are no longer available, having been removed from NFT marketplace OpenSea “based on a claim of intellectual property infringement.” It’s not clear how many (if any) managed to sell.

In November 2021, around the time Bike Club NFT was launching, Wout van Aert became one of the first pro riders to launch his own NFTs. In combination with his Jumbo-Visma team and NFT company Momentible, the Belgian made three unique NFTs available, each celebrating a big victory with a piece of animated artwork.

While many derided Van Aert and co, the project was a success. Van Aert’s 2020 Strade Bianche NFT sold for 4.48 WETH – approximately US$18,800 at the time. The NFT celebrating Van Aert’s Mont Ventoux stage win at the 2021 Tour de France fetched 4.2 WETH (around US$17,600), and the one commemorating his Champs-Élysées win at the same Tour sold for 4 WETH (~US$16,800).

Van Aert's Champs-Élysées NFT.

As with the Colnago NFTs, none of Van Aert’s NFTs appear to have been sold beyond that initial sale. That said, even managing to sell the NFTs to begin with is a success compared to some other ventures.

Project Fuerza

In July 2022, a new project named Project Fuerza caught the attention of some in the cycling scene by selling NFTs in collaboration with a bunch of big-name pro riders. Created by renowned cycling coach Hunter Allen, Fuerza claimed to be the “first in the world to combine human biometric data into the artwork”. More specifically, buying a Fuerza NFT wouldn’t just give you a piece of digital art inspired by a specific race the rider had done; you’d also get the rider’s data file from that race.

The launch of Project Fuerza was headlined by an extremely ambitious Peter Sagan collection* including several NFTs priced at more than US$1 million. The most expensive of those NFTs was entitled ‘Champagne’ and was priced at 7,474 ETH – approximately US$11.9 million at the time.

(*An article about the Sagan collection, published on the Outside-owned CyclingTips in November last year, angered Outside management, who were in the midst of trying to salvage the struggling Outerverse project. The article was pulled off the website, but can be found elsewhere online.)

Sagan wasn’t the only pro cyclist involved in the Fuerza project. Mark Cavendish (who’s actually had several NFT projects), Geraint Thomas, Rohan Dennis, Dan Martin, and Zdenek Stybar were just some of the many who also had their own collections. While none of these other athletes had NFTs priced as high as Sagan’s, all Fuerza cyclists had one thing in common: their NFTs didn’t sell.

In a recent email to Escape, Fuerza founder Hunter Allen confirmed that of the roughly 1,500 NFTs created, not one of them sold.

“Not a single sale,” he said, before adding: “Project is still alive and there. And with Sagan retiring, his NFTs are even more rare now.”

Project Fuerza was still creating cycling NFTs until late August 2023 and they’re all still available (for reduced prices*) on OpenSea. But the project has more or less stopped.

(*That hyper-expensive Sagan NFT, ‘Champagne’, doesn’t appear to be available anymore, and most of the Sagan NFTs are now priced at between 1-5 ETH – roughly US$2,000-$10,000. One NFT, commemorating Sagan’s second Worlds win, is currently on sale for 322 ETH or US$645,000.)

Grand Tour cash-grab

Race organisers got on the NFT bandwagon too. In May 2022, the Giro d’Italia announced it had created a collection of Giro-themed NFTs with NFT marketplace ItaliaNFT, including digital versions of the race’s jerseys (US$49 each), the race trophy (the one available sold at auction for US$1,300), and even of the Giro d’Italia logo.

Seemingly unperturbed by public sentiment, Giro organisers offered race-themed NFTs again in 2023. The single NFT for the maglia rosa (which included a real-world Giro VIP experience, physical jersey and more) sold at auction for US$500. The single 2023 Giro trophy NFT was bought at auction for 0.6 ETH (US$1,200) and included a physical copy of all four of the Giro’s jerseys, each signed by the respective winners.

The 2023 Giro d'Italia Trofeo Senza Fine NFT.

Not to be outdone by its Italian cousin, the Tour de France threw its hat in the ring earlier this year with a bunch of collectible NFTs to coincide with this year’s race. Customers who were willing to buy or trade or play online games to collect an NFT for all 21 stages of the race, would have a chance to “win a VIP experience on the Champs-Élysées final stage”.

Smaller races have gotten in on the act, too. Like the Tour of Turkey which, in 2022, handed out NFTs to stage winners and made a limited number available for sale to the general public.

NextHash

But where much of cycling’s flirtations with NFTs and crypto have been relatively harmless – if a little ignorant of community sentiment – the Qhubeka NextHash sponsorship debacle was something else entirely.

In mid 2021, after many months of uncertainty about the future of the African team, an apparent lifeline came from an unlikely place: NextHash, a mysterious crypto company with seemingly more offices than employees. Predictably, the news of NextHash’s sponsorship of the Qhubeka team was met with great concern – concerns that turned out to be well-founded.

After touting a forthcoming NFT collection, NextHash failed to pay the majority of its sponsorship, contributing to the closure of one of the peloton’s most beloved teams.

If the cycling community was already sceptical of NFTs and the crypto world to begin with, the NextHash saga only reinforced those feelings.

And then came the crash

Cycling’s dalliance with NFTs was a brief thing; a short but confusing whirlwind of confusion and head-shaking. Over the course of a couple years, several organisations and individuals had planted their flag in the new and exciting world of Web 3.0, hoping to get an early-mover advantage. Looking back now though, whatever momentum there was – whatever global NFT wave they were riding – would all soon disappear.

After the NFT market grew rapidly in 2020 and into 2021, it peaked in August 2021 with a total monthly trading volume of US$2.8 billion. In May 2022, the Wall Street Journal reported that the market was collapsing. And by July 2023, the NFT market was doing just US$80 million in trade – 3% of its peak from a couple years earlier.

Which brings us back to the independent report we referenced right back at the start; the one saying that 95% of all NFTs are now worthless. Written by the team at Web 3.0 community dappGambl, the report also revealed that 79% of all NFTs have not been sold, a clear indication that supply has easily outstripped demand. In the words of the report’s authors: “a significant portion of the NFT market is characterized by speculative and hopeful pricing strategies that are far removed from the actual trading history of these assets.”

Project Fuerza’s Peter Sagan NFTs, anyone?

The future

So what now? The NFT market has collapsed and the FTX debacle has helped to destroy most of whatever public enthusiasm remained for NFTs and crypto more broadly. So have we seen the last of NFTs here in cycling?

Well, if the daapGambl report is to be believed, “NFTs still have a place in our future.” The report’s authors say the sort of hype seen in 2021 was never going to last, but that once things settle down “we will start to see an evolution within NFTs.” That perspective is shared by Paul Willerton of Bike Club.

“I don't think it's over,” he says. “It was a big setback, though. The whole FTX thing … we have to get through this period in the press before we're gonna see a bunch of green shoots and [can] bring the public back into the space. It was pretty devastating.

“The important thing that people have to understand is that it was not that the technology failed. The blockchain didn't fail, Bitcoin didn't fail, Etherium didn't fail. They went on, as if nothing ever happened. What failed was trust in human beings and institutions, because that was where the fraud occurred.”

(It’s worth noting that FTX isn’t the only Web 3.0 giant where questionable human behaviour has occurred recently. Just last week, the world’s biggest crypto-exchange, Binance, and its CEO, Changpeng “CZ” Zhao, pleaded guilty to money laundering. CZ has resigned and Binance has been forced to pay a total of US$4.3 billion in fines.)

According to Willerton and daapGambl, if and when NFTs come back, they’ll do so in a different form. They won’t just be about owning a piece of digital art. Rather, in the words of the dappGambl report: “NFTs are likely to increasingly pivot from mere collectibles to assets with tangible utility and significance. In this ever-evolving space, the future of NFTs will be shaped not by speculation, but by genuine value and utility that they bring to their holders.”

Willerton agrees.

“I think when human beings see an NFT, they see a JPG or a digital piece of art and they say 'How can that be worth anything?'” Willerton says. “But what they're not seeing is the uniqueness and privacy of that address and what that opens up.”

Willerton and his Bike Club co-founder Shane Cooper are excited by the possibilities that still exist in the NFT/blockchain space.

“You could issue a title NFT that says you're the official owner of this bicycle, and it creates provenance,” Cooper says. “And so if, let's say Mark Cavendish has a bike, that provenance can carry on 25 years from now. ‘That was his bike and these were the races.’ They can do so much in record-collecting and title ownership and proof of ownership. That's what excites me.”

Colnago has actually been playing in this space for a couple years now.

Since 2022, new Colnago frames have been sold with an attached NFC tag (NFC is the technology used by contactless bank cards). By scanning that tag with their smartphone, a rider can link their new bike with their crypto wallet, proving their ownership of the bike (and that they have a legitimate Colnago product).

Manolo Bertocchi, marketing consultant at Colnago, tells Escape that Colnago has adopted blockchain technology to “solve some problems that happen often in the life of a bicycle”.

For starters, there’s theft deterrence. “I can steal a bike and, if I’m caught, no one can prove that the bike is not mine,” Bertocchi says. “There isn’t anything such as the public register [linking an individual and the bike]. With this technology we are creating exactly this: a public, accessible, safe and stable registry, which allows people to claim that the bike they bought is a) original and b) belongs to them.”

That originality and authenticity is a big part of the puzzle for Colnago. “High-end bike producers lose millions each year in lost sales due to the presence of counterfeit products in the market,” Bertocchi says. “This technology allows a user to immediately identify a bike as an original Colnago.”

Which links back in with the idea of provenance and being able to trace a bike’s history.

“Today, if I buy the Colnago C40 that [Johan] Museeuw used to win his third Ronde van Vlaanderen in 1998, I have to trust the vendor that that is the actual bike,” Bertocchi says. “With the blockchain technology now, because we have registered the bikes that were in France on the second rest day of the Tour de France 2023, the team can safely sell them or show them and demonstrate that that V4Rs was actually used by – say – [Tadej] Pogačar during TdF 2023.”

Cooper and Willerton also see potential when it comes to the way NFTs/blockchains could be used in the bike sales pipeline. They argue that the technology could help streamline the process for bike brands.

“If you’re Trek or Specialized, or whoever, and you believe that you have a road bike model that's going to be successful in 2025,” Willerton says, “at some point in 2024, you're going to have to go to your factory, and put in an order for X amount of each size of that frame, and then build those bikes. You may lay out 50% of the money, you may send them 20%, whatever.

“That's six months or a year ahead of time, then you have to land those products, distribute them to your retailers, and somehow they need to move that product at something close to a retail price in order for this to be a successful endeavour for everyone.

“Well, in the case of an NFT, it is possible to pre-sell that bike so that the customer can hold it in a digital form in their wallet, and that essentially represents the future physical bike. When the bikes come in, they can then transfer that token or redeem that token or NFT for the physical bike, or they could sell it to someone else.

“It makes no difference to say Trek or Specialized in that moment, because they already received their money ahead of time, sort of like crowdfunding.”

While we’re not seeing new Web 3.0 products pop up in cycling (or in general) like we were in 2021, the sport does still have links with the technology. Beyond Colnago’s efforts, Slovenian crypto company NiceHash is a key sponsor of that country’s national team and has its logo plastered across the chests of Tadej Pogačar and Primož Roglič.

NiceHash sounds a lot like NextHash, and in a ‘Sliding Doors’ kind of way the two are linked – NextHash’s founder gained control of 35% of NiceHash when first entering crypto, failed to actually come through with the promised funds, and got sued by them in 2019.

The infamous NextHash, meanwhile, is still involved in cycling too. It is a sponsor of the UCI Track Champions League (TCL), despite its role in the closure of Qhubeka NextHash in 2021. The details of the NextHash x TCL partnership aren’t clear exactly, but NextHash is described in a press release as “the state-of-the-art blockchain platform and financial services provider” involved in the delivery of Warner Brothers-Discovery’s “first NFT collections in 2023 inspired by iconic sports disciplines it promotes.”

Those NFTs don’t seem to exist yet. When contacted by Escape with some questions about where those NFTs are, whether Warner Brothers-Discovery (WBD) had experienced any issues with NextHash, and whether they were aware of NextHash’s unfortunate history in cycling sponsorship, WBD responded with “we will politely decline the opportunity to comment.”

Gone, but not for good

It’s fair to say that NFTs have been viewed with great scepticism by the cycling community ever since they first emerged, and that feeling prevails today. Whether it’s a media company, a rider, or a race organiser creating the NFT, the response has always been much the same.

Some cycling NFTs have worked, in the sense that they actually sold (Wout van Aert’s three NFTs for example) but others certainly haven’t (like Project Fuerza). And while consumer sentiment towards NFTs and crypto more generally is arguably at an historic low, there’s no guarantee it will stay that way. It might be that, at some point in the years to come, NFTs have a second coming; that creators find a way to make them actually useful enough to override the overwhelming negative sentiment they’ve so far attracted.

It’s a tall order, and it’s going to take time. But if you’re thinking you’ve heard the last about NFTs more generally, and in cycling, maybe don’t celebrate just yet.

Did we do a good job with this story?