Few things in a bicycle mechanic’s day can fill a swear jar as efficiently as internal cable routing. A quick gear cable replacement gone wrong can result in a game of fishing without bait or a bike being turned to pieces.

This is one of those topics that I deliberated over covering. Internal cable routing is one of those dark arts of the mechanic world, where giving away such tips and tricks may be viewed as giving away the lunch of mechanics. Heck, I feel oddly protective about a few of the things shared here.

Still, I truly believe that the sharing of information raises all boats. I hope both professional and hobby mechanics can benefit from at least some of what I've written below. At the same time, the wrenching-curious can gain a greater understanding of how some jobs are done.

Internal cable routing is a topic with plenty of nuances that can only be learned through doing. This edition of Threaded covers just a few tips, tools, and tricks that I find to be day-savers when dealing with frames with internal cable routing. However your results may vary based on the specific bike, component, or situation.

It’s also worth mentioning that what’s covered is how I tackle things. Other mechanics employ many other tricks, and if you’ve got one such trick, please consider sharing it in the comments.

If you worry about missing an edition of Threaded, you can sign up here for free to get an email notification.

Knowing what you’re dealing with

Many of the latest bikes with hydraulic disc brakes and electronic gearing have largely simplified working with internal cable routing. Meanwhile, when it comes to bikes with mechanical derailleurs or brakes, it can be a true guessing game of how a cable may be placed within a frame. And in rare cases, it's a game where the rules are only realised once things are pulled apart.

Sometimes brand-provided schematics or service manuals can help reveal what’s inside before you begin, but commonly, you’ll need to figure it out yourself. For that, it’s worth knowing the various ways that cables can be run through a frame.

The most common routing method today is full-length housing, meaning the outer cable housing is uninterrupted between the lever/shifter and through to the derailleur/brake. It’s rare to find a modern full-suspension mountain bike, e-bike, or even gravel bike without such full-length housings. Dropper posts are also almost always matched with full-length housings. Similarly, bikes routing gear or brake cables through a headset will certainly feature full-length housings. And likewise, if you’ve got hydraulic disc brakes, you’ve got a guarantee that there’s a continuous hose between the caliper and the lever.

Such uninterrupted housings can typically be spotted by how they enter and exit the frame, or can be revealed by gently pulling on them and seeing if there’s movement (beware of some cable guides that physically clamp onto the housings which will prevent such movement). These housings/hoses often sit loosely within the down tube of a bike, but a small number of premium bikes will have guided tubes (e.g. guided routing) in place to make installation and replacement a straight shot where the tricks in this article probably aren't needed.

Next, we have segmented housing, where the housing is split into sections and slotted into provided cable stops/guides/holes. In most cases, you can spot segmented housing by the presence of a ferrule (aka housing end cap). However, in some cases, the ferrule may be hidden from view or simply not used.

Segmented housing means that inside the frame there’s either a bare inner cable or some form of a plastic guiding sheath. The problem is, it can be tough to know what’s in front of you and the techniques can vary slightly for each.

Patience and forward-thinking

Perhaps the best tool of all is thinking through the task before just yanking at cables. Consider what type of cables you’re dealing with, how you may be able to access them most easily, and what you’ll do if the proverbial shit hits the fan (a genuine anxiety with modern e-bikes).

While not applicable to all bikes (especially those with guided routing), the general professional approach is never to pull out an existing cable without having a replacement cable or temporary wire take its place. Most learn this lesson at least once.

You may also consider what components you could remove to make the task infinitely easier. I commonly start by looking for an access hatch at the bottom bracket area to see if I can see the cables and how much access is offered. If access is limited through such a hatch, then often you’ll gain access to the cables through the bottom bracket shell. In these circumstances, I’ll remove cranks and bottom brackets in order to overcome any guesswork from the cabling process. Some good press-fit bottom bracket removal tools can be hugely helpful here.

Also look for where the cables enter and exit the frame. Are the cable guides removable? Do they pinch onto the cable housing/hose? Or maybe it’s just a rubber plug?

And it may seem obvious to read, but whenever replacing a cable, take your time to consider the routing path, the pieces that need to be installed, and in what order. For example, if you removed a bolt-on frame cable guide, then you’ll need to consider its orientation, perhaps a ferrule, and the housing path before routing the cable beyond it.

Regardless of your problem, patience is a virtue. Other virtues are great lighting and a good work stand that will help to keep the bike still and at an angle that lets gravity assist with the routing task.

Also turn down the volume on that episode of Geek Warning and allow your senses to guide you. Noise of how a cable is or isn’t moving through the frame can be helpful. Feeling for resistance and looking at whether a cable is curling up are equally useful.

Threaded barb tools for housings and hoses

For full-length housing (and brake hoses), my go-to method involves using a threaded-barb routing tool. There are two variants of such a tool. The first is the simple RockShox Reverb-style barb that allows you to thread a new length of housing/hose directly to the old. This tool is just a few dollars, and while it works, I find I more easily get a secure hold with the wired variant.

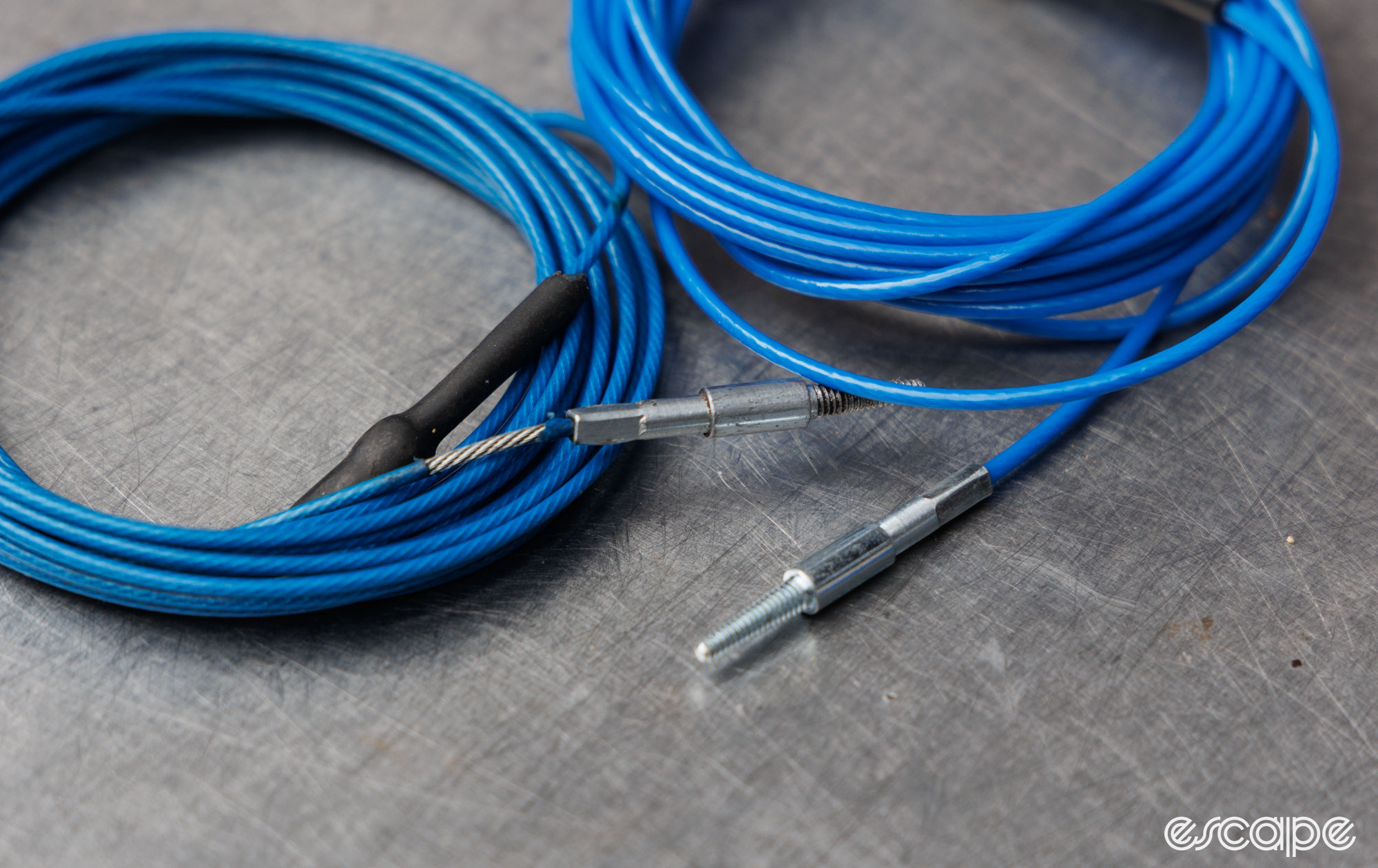

The wired variant is effectively a length of inner cable with a threaded barb crimped (or threaded) onto the end of it. Park Tool, IceToolz, Pro Bike Gear, ZTTO, and several others sell cable routing tools that include such a thing (my thoughts on them are shared later in this article), and for me, the barb-ended wire is always the most useful piece within each kit. It is possible to make your own with a small screw, a cable end cap crimp, and an inner cable, but you’ll want high confidence in the crimp security before using it.

Such threaded barb tools can expand or damage the end of the housing/hose they’re attached to. For this reason it’s good practise to give yourself a little extra length of housing that you can then trim off when it’s all in place.

Alternatively you can avoid the specialist tools and simply run a long inner cable through the existing housing. You then carefully pull the housing out while keeping the inner cable in place. I’ve had mixed results with this method over the years, namely whenever friction or tight bends are involved.

And one other method (although not one I use) is to put a number of bends into an inner cable until it locks itself into the housing. You can then pull the housing out, leaving the inner cable in place. Again, you’ll want to check that you’re getting a firm hold from the bent inner cable before trying this.

Plastic sheath for bare cable routing

OK, you have a frame with segmented cable housing and need to replace the inner gear or brake cable. There are many ways to tackle this problem; mine involves using a piece of plastic string/tube/sheath.

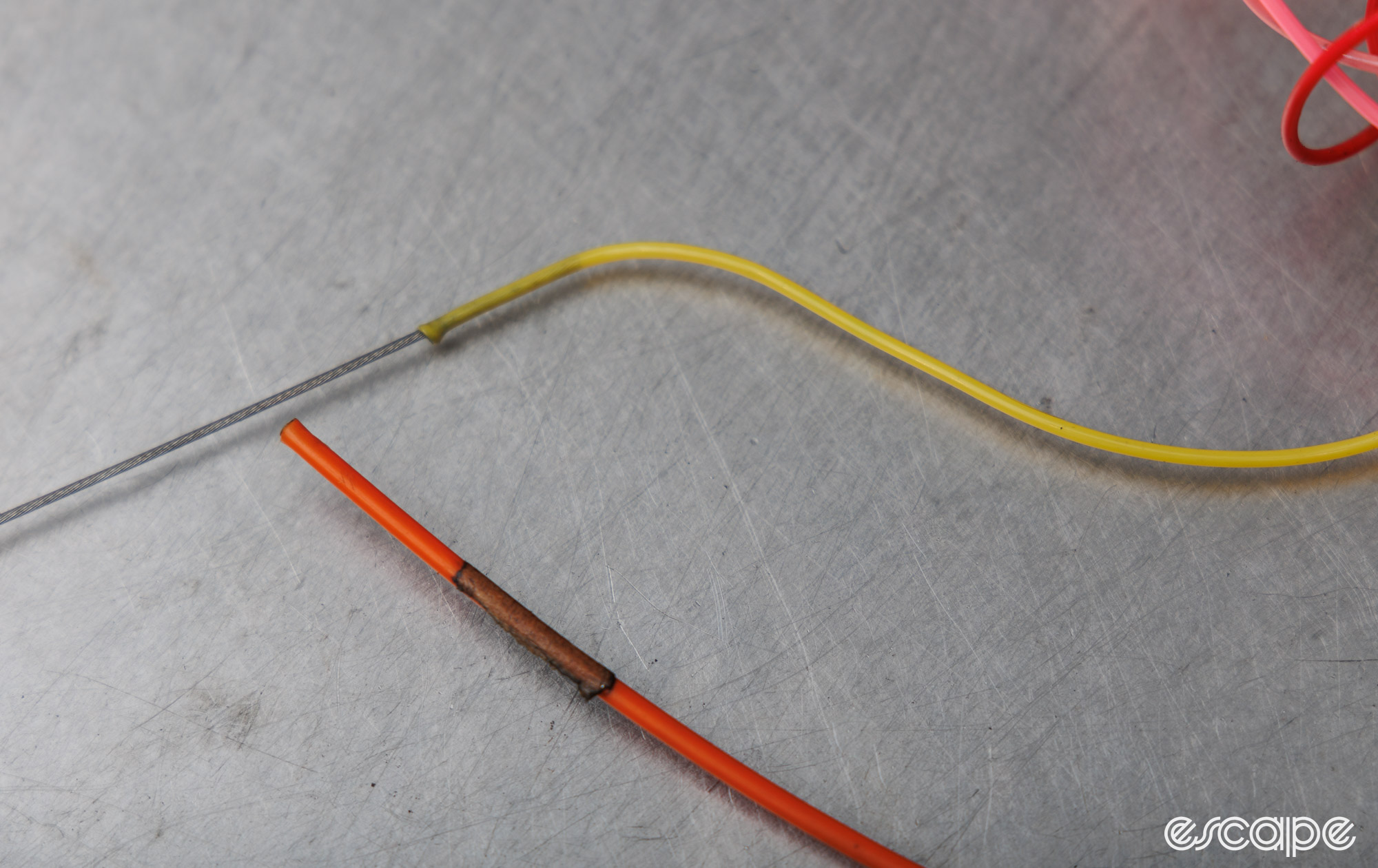

The plastic sheath is attached to the old inner cable before it’s pulled through the frame and left in place of the cable. Take care to pull gently, and not pull it too far that the opposite end of the plastic tube gets lost into the frame.

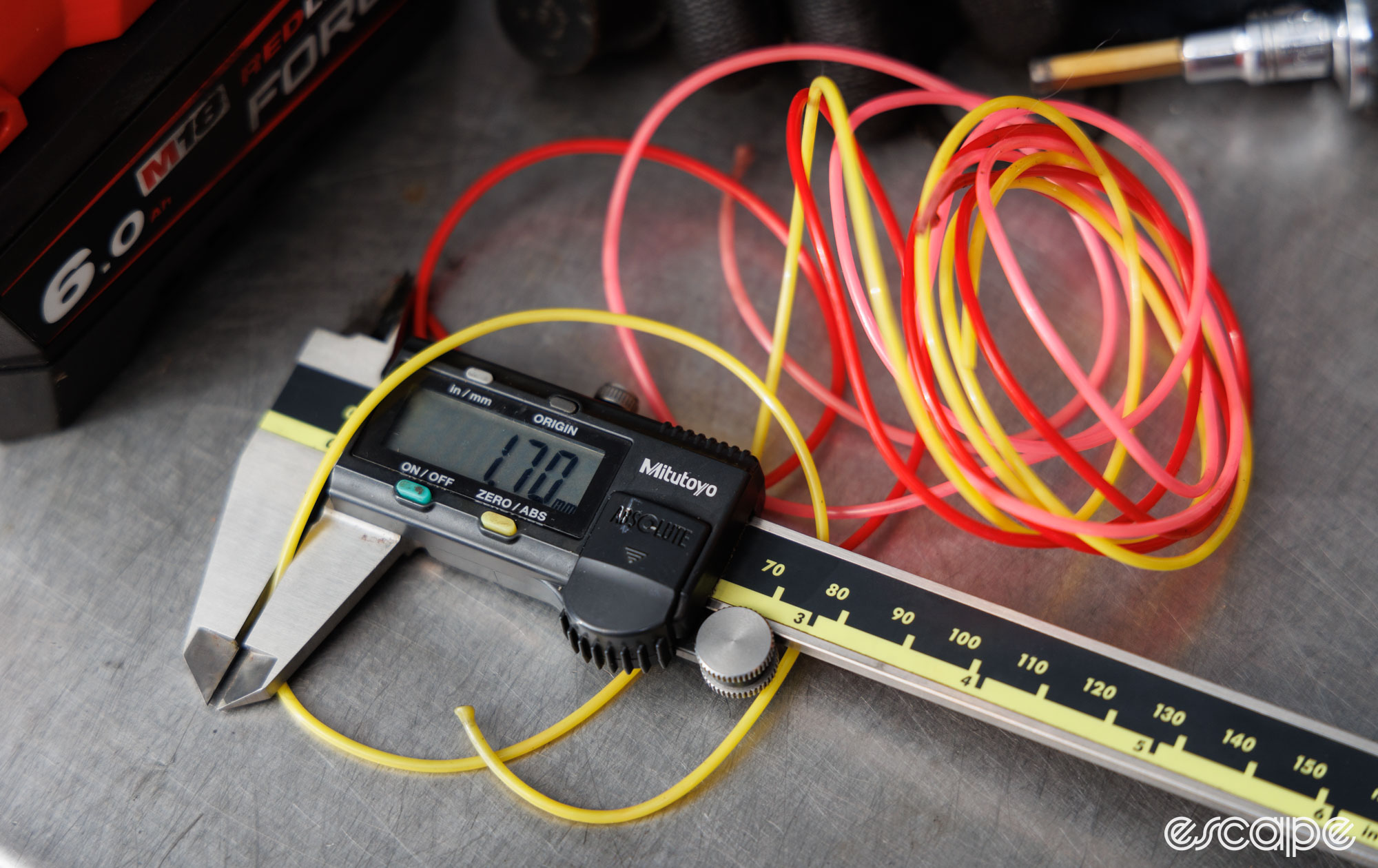

Such plastic tubing is often supplied with new framesets for easing frame assembly and so well-stocked bike shops will often have spares. Alternatively, you can purchase similar by finding thin "PTFE tubing” (commonly found on eBay or similar stores) with an internal diameter marginally bigger than the inner cable (roughly 1.1 or 1.2 mm for gear cables, or 1.6 mm for brake cables).

Or my absolute favourite (and until now, a prized secret of mine) is hollow-type plastic string from a craft store (commonly used for braided bracelets or beaded crafts). Often the centre hole in this stuff is too small and so I’ll carefully enlarge the end with a heated pick to easily fit over the edge of an inner cable. This stuff is no larger in diameter than the cable it’s replacing, has a bit of stretch to it, and you can colour-code your work if doing more than one cable at a time.

In rare circumstances, the use of such plastic string/tubing fails due to silly sizing limitations at the guides (the hole is too close in diameter to the inner cable). This can be rather annoying to come so close to an easy cable replacement, to then be forced to pull the bike apart (typically just the crank/bottom bracket) or go on a fishing expedition. Frames like this are annoying.

Magnets

Most cable routing tool kits rely on the use of magnets. Tools such as Park Tool’s IR-1.3 (link goes to an explainer video) feature magnets on each guiding wire, where two guiding wires can be inserted into a frame from opposing ends and then magnetically meet in the middle. Alternatively, these kits also provide a strong magnet to help with routing loose inner cables or guiding the tool’s guiding wire to daylight.

Of course, you don’t need a fancy bicycle-specific tool to employ a magnet. Any strong magnet can be used to help with guiding an inner cable or a segment of housing in a desired direction. Similarly it’s possible to make your own cable routing kits with some inner cables, some small magnets, and a small dose of ingenuity (plus glue, heat shrink, and/or crimps).

Pokers, grabbers, and an inspection torch

An assortment of surgical-like tools can also come in handy. Long nose pliers, bent spokes, or an assortment of picks can also be useful for catching the end of a cable or housing and bringing it out to play.

My absolute favourite grabbing tool is long Alligator forceps, a tool I’ve featured in Threaded before. It’s perfect for reaching down into seat tubes to grab hold of dropper cables or reaching into the edge of poky bottom bracket shells for Di2 wires.

My next favourite tool is a quality and slim inspection torch. I like the Coast A9R because its ultimately slim diameter allows me to shine light into just about anywhere in a frame, whereas most flashlights or inspection torches can only shine light from outside of the frame. Light is handy!

And because it’ll get mentioned in the comments, I will say that I’ve had mixed results with digital borescopes. They’re a cool tool, but the tiny camera can make it hard to understand the perspective you’re looking at and how to adapt your work to it. I know others swear by these, but I typically only find them useful for the rare times I encounter a blocked pathway within a frame. Such tools are forever getting better (and smaller!), so perhaps I’ll change my mind on these in future.

Vacuum cleaner and dental floss

If you’ve ever watched a GCN video on internal cable routing you’ll probably be all too familiar with the idea of using a vacuum cleaner to pull a length of dental floss or stitching thread through a frame.

If successful, you then have a thread/floss that you can tie onto the new cable and pull back through from the direction the thread began.

It’s a clever idea, but one I’ve had less success with when compared to everything explained above due to the thread getting caught up inside the frame or then struggling to tie it securely to the housing. Still, it’s an idea for home mechanics staring down a frame with no cable in place and no fancy tools to ease the task.

Sidebar: Hands-on with commercial cable routing tools

Park Tool IR-1.3

Now in its third iteration, the Park Tool Internal Routing kit was one of the first daysaver solutions and remains a common sight in bike shops. In addition to a strong magnet and a RockShox Reverb-style dual-ended hose barb, the kit provides individual wires for each fitment type (five wires in total, including one for new Shimano SD300 Di2 wires).

Having dedicated wires for each form of cable/wire/hose connection may make it messier to pack up, but it brings huge benefits. Firstly, there are no tiny threaded bits to misplace. And more importantly, having the connection element permanently crimped to the wire means there’s no risk of unintentionally unwinding the tool during use.

I’ve used these Park Tool kits for years and feel they more than pay for themselves in time saved. That said, I do wish the new SD300 Di2 wire had a slimmer-diameter connection end, and that the threaded barb was shorter in length to better get around tight corners and curves which are surprisingly common in frames and handlebars.

Still, this kit remains my first port of call for routing full length housings, brake hoses, and electronic gear wires. I don’t use this kit (or any of the covered kits) for internally routing bare inner cables; rather the previously mentioned plastic sheath is my preferred option for such tasks.

Price: US$73.

IceToolz Internal Routing Tool

The IceToolz routing kit was clearly inspired by Park Tool’s kit but it offers a few points of difference in addition to being cheaper. The connection ends of the wires are shorter than those from Park and are therefore marginally better at making tight curves. Unfortunately, they come with an increased diameter that can present other interference and usage issues in certain frames.

The IceToolz kit is a little more limited in the types of tasks it’ll handle, too. Namely the kit hasn’t yet been updated to work with Shimano’s skinnier SD300 Di2 wires. Overall it’s a good kit made even better by the price. That said, I’ve experienced more fitment issues from the wider-diameter connection ends than I have with Park Tool’s longer-length connectors. Your results may vary.

Price: approx US$43.

Pro Bike Gear Internal Routing Tool

With the form factor of a folding multi-tool, this unassuming tool from Pro Bike Gear (a Shimano brand) is surprisingly awesome. In fact, it’s my second most used routing tool after the Park Tool kit.

It offers a single routing wire with various connectors that thread into place. The connectors are as slim as the Park Tool, but with a reduced rigid length that makes the tool better for jobs with tight bends.

Plus, the newer version of this and the Park Tool IR-1.3 are the only two tools with dedicated connectors for routing Shimano SD300 Di2 wires. And the connector in the Pro is a slimmer (superior) size to that of Park’s.

So why is this not my one and only? Firstly the single provided wire can be limiting if you’re doing a job that requires multiple wires in use. It won’t let you do the Park Tool magic trick of dropping two magnetic wire ends into a frame and having them connect to each other. It's a tool with many easily lost small parts that cannot be bought separately from the tool. However, the biggest issue is that the connectors are threaded into place, and with enough careless twisting, it is possible to accidentally disconnect the connector from the guiding wire (yes, I called myself mean things).

Price: US$60.

Jagwire Pro Internal Routing Tool

A cable routing tool from a bicycle cable manufacturer? It sounds promising. And with a small and elegant form factor it looks promising, too.

That said, Jagwire's little tool relies far too heavily on guiding things wholly with magnets for my liking. Whenever I’ve tried to use this tool I’ve found myself frustrated by not having a simpler cable that I can just pull through a frame. Or in other occasions, I’ve wished the provided bendy magnet would reach further than it does. Still, it's at least made nicely and I like that Jagwire sells spares.

Price: US$40.

ZTTO Internal Routing Tool

A truly budget option from Chinese online marketplace AliExpress, this ZTTO kit is most similar to the Jagwire tool in that it’s largely reliant on the use of magnets.

There is an inner cable with a magnet provided, but the inability to attach the hose/housing barb or Di2 wire holder to this cable means you'll almost certainly be relying solely on magnets. It’s cheap and not useless, but it would be a whole lot better if the provided inner cable had a threaded end.

Price: approx US$12.

A summary

I get regular use from both the Park Tool and Pro Bike Tool internal routing tools. They each have their strengths and weaknesses, and until someone makes a better option, I’ll continue to keep both options handy.

Meanwhile, if you’re a home mechanic on a budget, then I’d suggest trying the ZTTO, which should help with the most commonly experienced needs. If you want to spend a little more, then the Pro Bike Gear tool has some nice features on offer, especially for those dealing with newer Di2 wires or stubborn housings.

If all else fails …

Escape Collective offers a tool in case everything fails and you can’t bring yourself to look at the bike or its cabling again…

Classifieds. Yep, you could always sell the thing. With that shameless plug done, it’s time to draw the curtains on this edition of Threaded. Do you have a tip I didn’t cover? Please share it in the comments!

Coming up

The next edition of Threaded is never far away (it publishes every second Friday, or else, I’m told, I may lose a kneecap). We’re in the season of new tools and so you can expect another edition of New Tools Day within the next few editions. I’m also working on more torque wrench-related things, tools for travel, my favourite chain breakers, the best cable cutters, and oh so much more.

Subscribe to the Threaded email list (it’s free!) if you want to be alerted for whenever Threaded is published.

A special thank you to Escape Collective members and subscribers. Your support allows this content to exist and continue. If you’re not already a member and find value in these articles, please consider supporting Threaded’s continued existence with your wallet.

Did we do a good job with this story?