When it comes to cross-country mountain bikes, the lion’s share of the attention is devoted to the high-end, short-travel, full-suspension machines like the Specialized Epic 8, Trek Supercaliber, and Cannondale Scalpel. That’s perhaps as it should be for seasoned racers and/or buyers with deep pockets, but for newcomers coming from other cycling disciplines, kids, and the generally MTB-curious who will ultimately fuel the continuing survival (perhaps even growth?) of the segment, the aluminum hardtail is still where it’s at – and Trek’s third-generation Marlin line comes across as one of the better options out there.

Good stuff: Fantastic frame geometry, excellent shifting, good tires, looks great, generous tire clearance, easy-to-live-with semi-internal routing, sort of a rear thru-axle.

Bad stuff: Mega-heavy fork with minimal adjustability, tubeless costs extra, limited upgrade potential.

The basics

Looking at what goes into Trek’s latest-generation Marlin, there’s not a whole lot that leaps off the page, which perhaps shouldn’t be entirely surprising given most buyers at this price point will probably be making their decisions based on spec and aesthetics. In that sense, the Marlin is exactly what you’d expect.

The frame is a TIG-welded aluminum affair with chunky weld beads that do without the additional hand-sanding that can sometimes go with a higher-end alloy chassis. The layout is low-slung with a highly sloping top tube that offers heaps of standover clearance, and straight-gauge tubing is featured throughout.

The hydroformed shaping on those tubes is much more dramatic than the outgoing Gen 2 Marlin. The top tube is squished down almost flat to help soften the ride of the front end while the down tube sports a rounded trapezoidal cross-section to minimize twist under load; both are notably flared where they meet the straight 1 1/8” integrated head tube to increase front-end strength.

The seatstays are subtly flattened – presumably for the same reason as the top tube – and while the seat tube is basically round, it’s slightly curved to leave a bit more space for the rear tire with a welded-on gusset for the extension up top. Pretty standard stuff all around, so far.

The chainstays are where things get really interesting. They feature a bridgeless design to prevent mud build-up, and the S-bend at the bottom bracket is much more complex than before. Trek has also dropped both sides a bit as compared to the previous Marlin, and the changes help boost claimed tire clearance to a more useful 2.4” (up from 2.2”).

Further back, the previous Marlin’s open quick-release dropouts have finally gone away in favor of a hybrid setup that Trek calls ThruSkew. Make no mistake: the hub dimensions are the same as before. But whereas the old Marlin uses the common quick-release skewer, the new one gets a thru-bolt arrangement that Trek claims is more secure than an open dropout while still saving production costs as compared to the oversized thru-axles found on more expensive bikes.

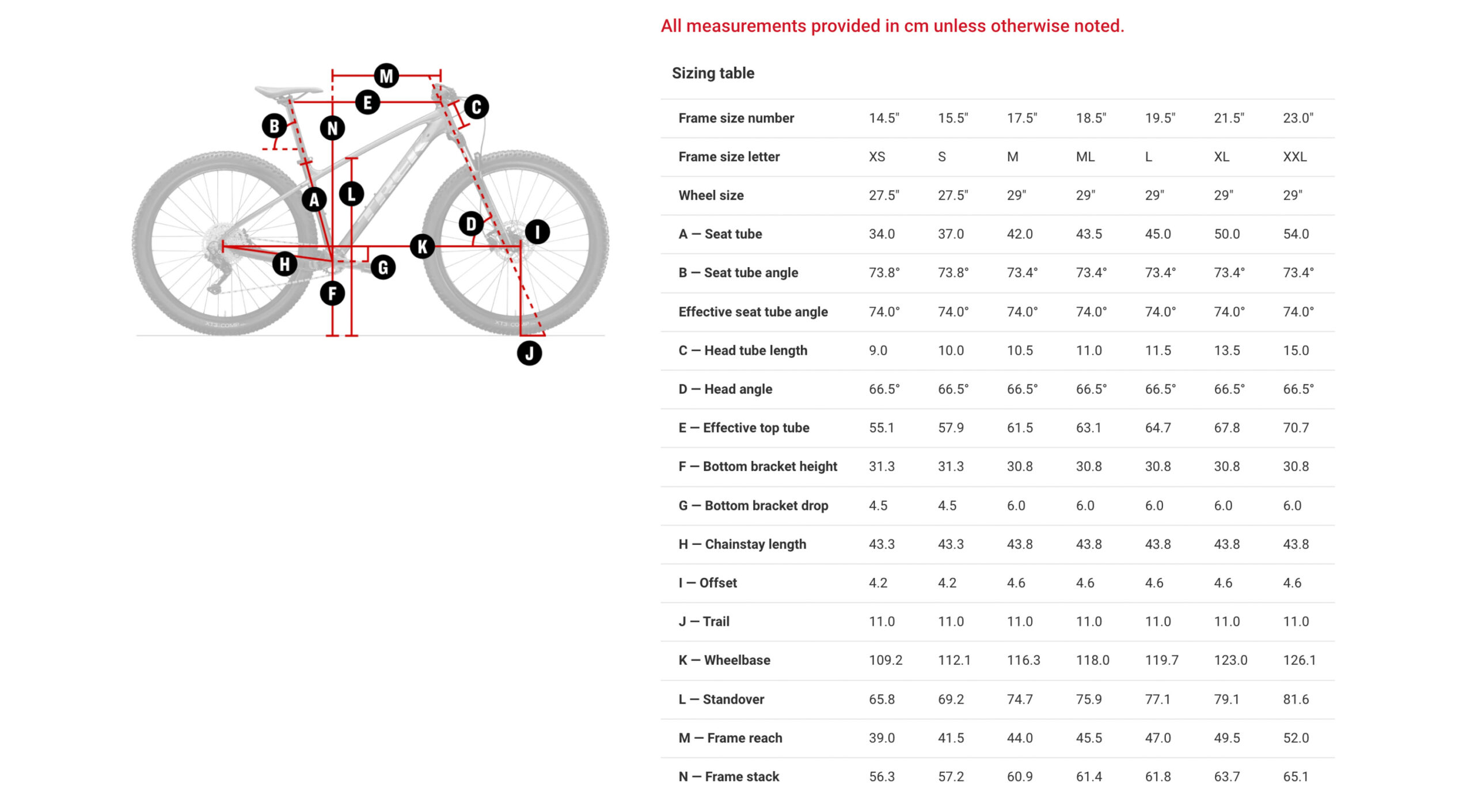

Far and away the biggest improvement lies somewhat beneath the surface with vastly more modern and progressive frame geometry. Compared to the Gen 2, head tubes are dramatically slacker across the board – by almost 3°, in fact – the seat tube angles are more subtly steeper by about a degree, reach dimensions have grown by a 15-54 mm (depending on size), and bottom bracket heights have dropped a few millimeters.

Taken together, the changes are intended to place the rider is a more central position between the wheels, and they also push the front wheel further out in front for more confidence on steeper and/or more slippery terrain, similar to trends we’ve seen more generally elsewhere in the mountain bike space over the past several years.

Impressively, Trek continues to offer the Marlin in seven frame sizes that are designed to accommodate a huge range of rider heights from 1.35 to 2.03 m (4’ 5” to 6’ 8”), with all but the two smallest sizes built around 29”-diameter wheels.

Other features include a conventional English-threaded bottom bracket shell, partially internal cable routing, and a big molded rubber guard for the driveside chainstay to keep things quiet and clean. There’s even a fair bit of versatility baked into the Marlin frame with mounts for a rear rack and kickstand, and there’s also an extra port in the down tube for a dropper seatpost should you decide to add one later.

Trek says a raw medium Marlin frame tips the scales at about 1,800 g, plus another 100-150 g for paint.

Trek offers the Marlin in four build kits, and for this review I went with a middle child to stick below that critical US$1,000 / AU$1,500 / £775 / €850 price point. In early April, Trek added new build options of the Marlin 7 (with a dropper post), 6, and 5, while still offering the pre-existing ones, which are themselves still current model year. It's somewhat confusing, not least to dealers, but for clarity my test bike was the dropper-less Marlin 7 build kit.

For that fairly modest sum, Trek outfits the Marlin frame with a 100 mm-travel RockShox Judy suspension fork, a 1x10 Shimano Deore transmission with an FSA Alpha Drive aluminum crank, 23 mm-wide Bontrager Kovee tubeless-compatible aluminum wheels rolling on sealed cartridge bearing hubs and wrapped with 2.4”-wide Bontrager XT3 Comp tires, and Shimano MT200 hydraulic disc brakes with 180 mm-diameter front and 160 mm rear Shimano RT26 rotors. Finishing kit is pretty basic aluminum stuff all around, capped with a Bontrager Arvada saddle and Bontrager XR Trail Comp lock-on grips.

It’s no lightweight in stock form at 14.12 kg (31.13 lb), but that’s pretty much par for the course.

Gone fishing

While there are definitely bikes that continue to push the envelope of just how long, low, and slack you can go, Trek has found a nice sweet spot with the Marlin and there’s a very good reason why this sort of thing has become so popular: it works. I’ve come to prefer this style of geometry on my personal bikes – both longer- and shorter-travel ones – because of how they provide more flexibility in where I put my weight in different situations and the added stability at higher speeds. But what really matters in the context of the Marlin is how that layout makes for a more forgiving setup than XC geometries of yesteryear.

If you chuck the Marlin into a corner that doesn’t have quite as much grip as you expected, the front end is more apt to just push a little – otherwise known as understeer – instead of immediately and unceremoniously dumping you onto the dirt. On steep descents, the Marlin allows you to stay centered over the bike instead of awkwardly shifting your weight rearward to keep you from feeling like you’re about to go over the bars. And yet on steeper climbs, the front end isn’t so long that you need to work to keep the wheel from lifting off the ground with each pedal stroke.

In other words, the Marlin’s geometry leaves more room for error as you continue to learn how knobby tires work on dirt, but also more space to grow your skills without constantly having to pick yourself off the ground and wonder what went wrong. Put in simpler terms, the Marlin’s modern frame geometry also just makes it fun and confidence-inspiring to ride.

The Marlin frame is pretty good in the more traditional metrics, too.

It pedals about as you’d expect for a hardtail (at least compared to lower-end full-suspension bikes), with pleasant levels of snappiness and feedback when you get on the gas and impressively good frame stiffness. I was expecting a backboard-stiff ride quality given the straightforward aluminum hardtail frame and thick-walled, 31.6 mm-diameter seatpost, but even that was a pleasant surprise. The Marlin is still a hardtail, of course, but even with those 2.4”-wide tires inflated a smidgeon more than usual to keep from pinch-flatting on all the sharp rocks I have around here, it’s actually reasonably smooth over rough stuff.

Bonus points to Trek for not following the lead of lower-end road bikes by routing the control lines through the upper headset bearing for absolutely no good reason whatsoever (aside from misguided vanity). The ports on the side of the down tube are clean-looking and effective, and although the foam tubing installed at the factory still allowed a bit of internal rattling on particularly bumpy sections of trail, it’s overall a very clean setup that won’t rub the paint off of the frame over time, either.

Build kit breakdown

It’s pretty easy for a product manager to do a good job on spec when the bike is an ultra-premium model with a five-figure price tag, but that task is far more challenging when you’re watching every last penny. Trek has gotten a lot of things right on the Marlin 7 Gen 3, but also left a fair bit of room for improvement.

Let’s touch on the high points first.

Trek likely saved a bit of cash in the drivetrain by speccing an FSA Alpha Drive crankset and KMC X10 chain instead of a 100% matched setup, but the Shimano Deore bits are there where it matters most and serve as a potent reminder that at this end of the market, Shimano absolutely obliterates the performance of its rivals. Individual shifts under normal pedaling efforts on the Marlin 7 were as smooth as could be, and even multiple shifts under harder efforts were consistently reliable. The whole setup was pleasantly quiet and feels impressively premium, too, and bonus points to Shimano for making the Deore pulley cage clutch a user-serviceable item. If there’s a better option than this at this price point, I’m all ears.

The Shimano MT200 hydraulic disc brakes are more ho-hum. The levers are weirdly long (probably because newer riders are more comfortable using two fingers instead of just one), but the lever action is light and snappy with a clearly defined engagement point and user-friendly mineral oil-based system. Pad clearance is fairly generous and it’s easy to set the calipers to run rub-free. MT200s aren’t exactly renowned for their power what with their two-piston format and fairly small pads, but the 180 mm-diameter front rotor helps boost the overall performance to more reasonable levels – a good thing since the RT26 rotors aren’t approved for use with metallic pad compounds. Overall, these aren’t going to blow anyone’s socks off, but they get the job done.

I usually don’t expect much for base-level mountain bike tires, but the Bontrager XT3’s tread design genuinely surprised me. The well-reinforced shoulder knobs and moderately squared-off profile offered grip through loose corners, with just enough intermediate tread for a smooth transition between being upright and leaned over. The center tread also sports a ramped leading edge and spacing that’s close enough that it doesn’t feel like you’re dragging an anchor behind you, but yet with enough open area to dig into softer dirt when available. They’ve even been wearing decently well, which is a good thing considering tires aren’t exactly cheap these days.

The Bontrager finishing kit was quite nice in general, actually. The Arvada saddle’s flat profile and firm padding offer good support, while the deep central channel keeps pressure off of your sensitive bits. The lock-on grips sport plastic, not metal, collars but still clamp tight and offer a secure hold with tacky rubber and a ribbed pattern that’s easy on the hands, and the aluminum riser bar is usefully wide at 750 mm. Heck, Trek even does size-specific widths here, with small bikes getting a 720 mm-wide bar and XS bikes getting a 690 mm one.

As for the stem and seatpost, they’re nothing special. I do appreciate that the former is compatible with Bontrager’s handy Blendr system of accessory mounts, while the two-bolt head on the latter is definitely easier to adjust and more reliable than just about any single-bolt system out there.

The list of not-so-great stuff isn’t necessarily longer, but it unfortunately includes some major drawbacks.

The RockShox Judy suspension fork is about as basic as it gets, with a steel coil spring on one side and a non-adjustable damper on the other. Spring preload can be increased via a handy crown-mounted knob, but spring rate is fixed – and unfortunately, too stiff for my 73 kg (160 lb) body weight. Although it should be straightforward to swap to a softer spring, RockShox doesn’t offer any alternatives.

New riders might find the handy crown-mounted lockout knob to be a plus, but not when it comes at the expense of adjustable rebound damping as I’d take the latter over the former any day of the week. Coupled with that overly firm spring, I found the rebound to be too fast for my liking, and the fork did only a marginal job of keeping the front wheel planted on the ground when things got even remotely tricky.

The wheels could stand some improvement for sure. The 23 mm inner rim width is on the narrow side – I run wider rims on my gravel bike – and although both the tires and rims are tubeless-compatible, Trek doesn’t use tubeless tape on the rims so that’s an additional conversion cost on top of the valve stems and sealant you already have to buy extra. Build quality was disappointing, too, with insufficient spoke tension on the rear wheel and enough popping and pinging to tell me neither wheel was properly de-stressed at the factory, none of which bodes well for long-term durability. And that external-cam front quick-release skewer? Have we learned nothing, bike industry? Mine came loose on the first ride and definitely needed an unusually high amount of lever force to keep it from happening again.

Another ding against the fork and wheels is their weight, as all three of them are seriously hefty items. RockShox doesn’t even bother to list an official weight for the Judy, but I can tell you its steel stanchions (and steel steerer!) push the actual weight of my test sample to just shy of 2.4 kg (5.29 lb). The wheels aren’t quite as egregious at around 2,300 g per pair, but the stock tires don’t exactly help matters at over 1 kg each.

Upgrade conundrum

One thing that should be considered for bikes at this price point is the potential for upgrades. Oftentimes, these bikes are purchased as a stepping stone in hopes of becoming more proficient at the sport, and it’d be nice if the bike could grow with your skills to some degree. In that sense, the Marlin 7 is … interesting.

Tires should always be the first items on that list as they have the biggest effect on how a bike – any bike – performs. You can thankfully get decent replacements for under US$100 per pair, and given how heavy the stock rubber is on the Marlin, you can also lop off hundreds of grams of rotating weight in the process. So skid away with those stock tires, my friends, skid away.

Another obvious addition is a dropper seatpost, which Trek facilitates with that spare internal routing port. The PNW Components Rainier is widely regarded as working well and reliable, and it’s less than US$200. Given how heavy the Marlin is already, why add weight with the dropper, you ask? Simple: control. Given the choice between a hardtail with a dropper and a full-suspension bike without one, I’d choose the former every time – and I don’t think I’m in the minority.

On the surface, upgrading the wheels and/or fork isn’t as straightforward since Trek has unfortunately limited your options with the quick-release hubs and straight 1 1/8” steerer, as even mid-range components have moved on from those antiquated standards long ago. That said, Hunt (and likely others) still offers good aluminum wheels with quick-release hubs for a few hundred bucks, and there’s heaps of potential in the used market since parts with those outdated fitments can be had for a song – sometimes even at local community bike shops where there’s a good chance someone has donated parts that can be purchased for next to nothing.

“On the front of the bike, thru axle costs are not only higher with hubs and axles, but also the forks themselves,” explained Trek mountain bike product manager Chris Drewes. “These costs trickle down to headset cost, and frame manufacturing costs as well. Rear quick-release saves cost in many ways. When you add in the cost of thru axles for frame manufacturing and thru-axle compatible hubs, there is a significant cost difference. That being said there are quite a few wheel manufacturers that offer endcap swaps with their higher-end wheels. Upgrading the Marlin, we see a lot of riders doing drivetrain/dropper post/cockpit upgrades rather than the bigger items like a fork or wheels.”

Would I have preferred that Trek gone with modern thru-axles and a tapered steerer? No question. But the reality is both are still the norm at this price range throughout the industry, and for a bike like the Marlin, I’m not sure I’d consider either a total deal breaker.

Sizing up some of the competition

There are a whole bunch of similar bikes at this price range – so many (and with so much international variation) that it’d be impossible for me to compare them all here. That said, it’s worth taking a look at how some of them fare versus the Marlin 7 Gen 3, keeping in mind that this is only a hypothetical look on paper as I haven’t actually ridden any of these other bikes.

First up is the Specialized Rockhopper Comp. Despite the similar frame and fork, it has a major weight advantage of over 1.5 kg, much of which is in the wheels and tires, which would likely make it feel fleeter on its feet than the Marlin. It’s also more XC-oriented in general with a 2° steeper head tube angle and shorter reach for quicker handling, and while those tires are substantially lighter, the faster-rolling tread won’t offer nearly as much grip, either. This is an interesting option if you’re seeking an aluminum hardtail with a longer-term eye on racing, but the Marlin strikes me as the better all-rounder.

Ok, and then there’s the Giant Talon 1. Giant historically has offered unusually strong spec for the money compared to other mainstream brands, and it’s no different here. Although most of the components are comparable to the Marlin 7, the biggest upgrade here is the house-brand SXC32-2 RL fork. The stanchions are larger in diameter for more precise handling, and along with the steerer, they’re aluminum for dramatically lower weight than what comes on the Marlin. The air spring drops weight even further and adds critical adjustability, and the hydraulic damper also includes adjustable rebound, all of which should make for a far more capable front end that’ll offer more control and speed.

Like the Rockhopper, the Talon’s frame geometry is on the more traditional side of things with a similarly steep head tube angle and short reach, but that fork alone is a big advantage over both the Marlin and Rockhopper.

Finally, there’s the Canyon Grand Canyon 5. Consumer-direct outfits like Canyon often blow mainstream offerings out of the water in terms of value, and the Grand Canyon 5 makes a strong case for that here. The frame is still QR front and rear with geometry that isn’t quite as progressive as the Marlin’s, the Suntour fork features steel stanchions and a steel coil spring, and the wheels are similarly basic aluminum units. If the claimed weight is accurate, it’s actually heavier than the Marlin.

However, you do get a proper Shimano external-bearing crankset and adjustable rebound on the fork, and at a price that undercuts the other three bikes mentioned here by about US$200-250. From a value perspective, this one seems tough to beat.

The final word

There’s a saying about buying a house that often comes to mind when comparing the pros and cons of various bikes: location, location, location. The idea there is that while you might be sucked into a home’s freshly renovated kitchen or additional bedroom, many of those features can be changed over time (albeit often at greater expense, but still). What you can’t change, however, is where the house is located.

What’s that have to do with bikes? In this case, location is analogous to frame geometry. Without question, the Marlin 7 Gen 3 isn’t the clear-cut best bike out there in terms of spec. If you want a more complete package straight out of the gate, there are obviously better options if you know where to look. But if you’re in it for the longer term, the Marlin’s frame geometry is so good that it’s hard to overlook. Despite the heavy fork and wheels, it’s the frame geometry that ultimately makes the Marlin so entertaining and capable – and arguably, the one most amenable to upgrades, quick-release dropouts and all.

If your budget allows, though, I’d nevertheless strongly recommend saving up a few extra pennies and splurging on the Marlin 8. It costs US$300 more, but if you even think you’re in it for the long haul, you’ll thank me later for the substantial fork upgrades included there and the stock dropper seatpost, both of which will ultimately save you money later on.

Whichever way you go, if you’ve exclusively been a drop-bar rider for the last few years and are thinking of heading to the dirt, there are plenty of good options available that won’t cripple you financially. Hope to see you out there!

More information can be found at www.trekbikes.com.

Did we do a good job with this story?